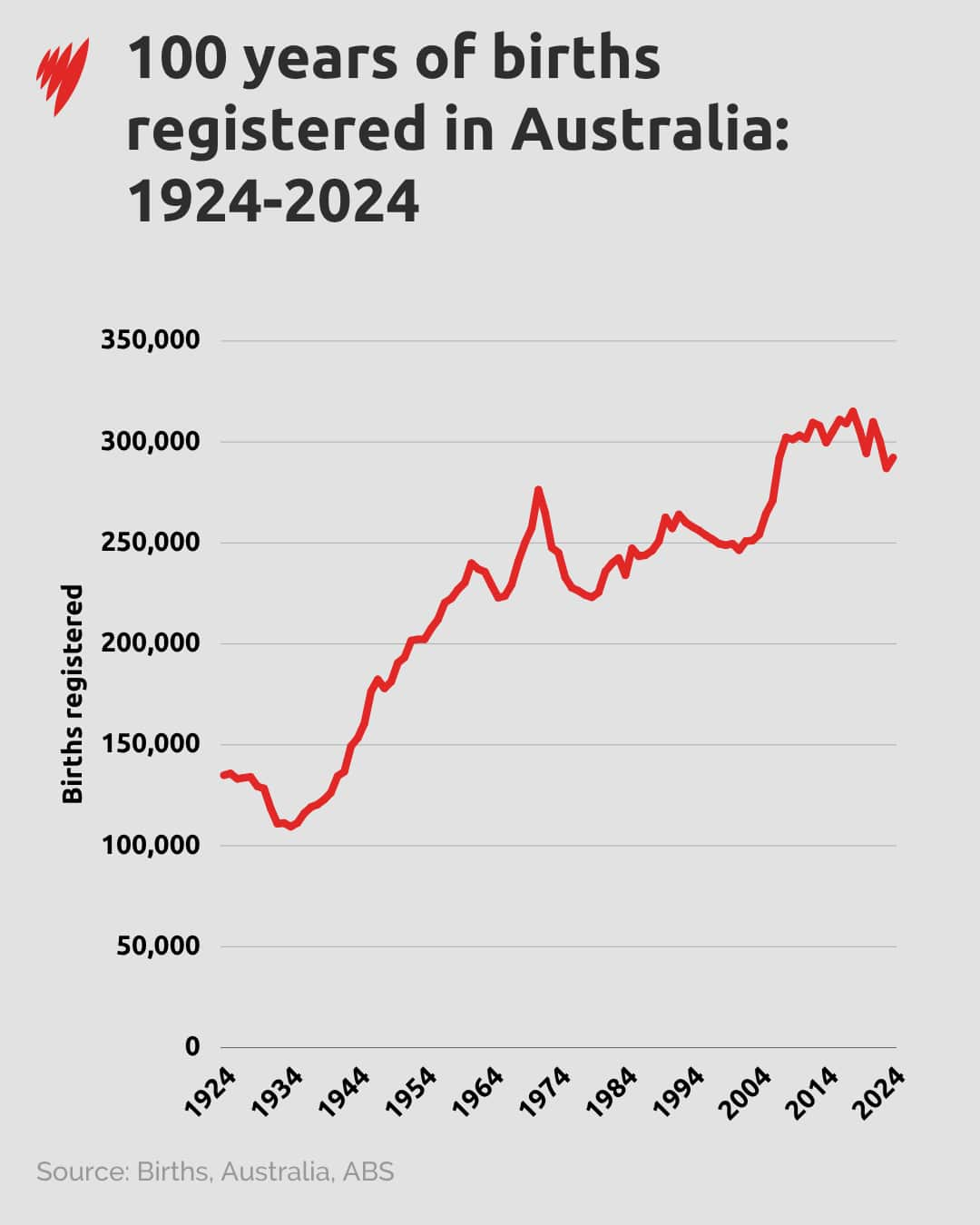

Australia's birth rate is at a record low, according to figures released on Wednesday by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

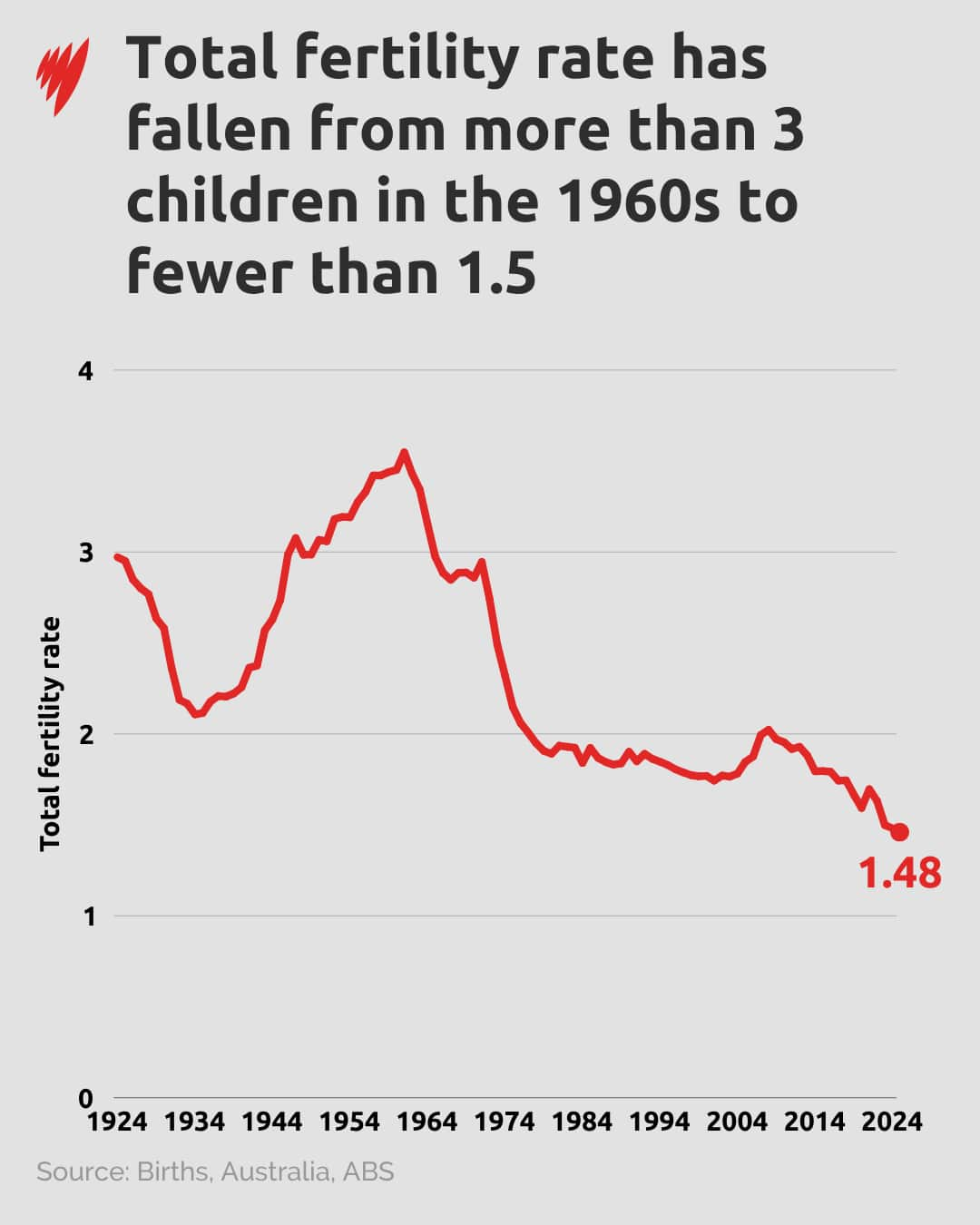

The total fertility rate in 2024 was 1.48 births per woman on average, a dip from 1.5 the previous year.

Birth rates are falling around the world, but experts say Australia's is heading past the point of no return.

In Australia, the total birth rate has steadily declined over the past 30 years, from 1.85 in 1994.

The recommended replacement rate — the amount of births per woman required for a population to replace itself across generations — is 2.1 births per woman.

But Australia hasn't seen a fertility rate that high since 1975.

Birth rate at 'rock bottom'

Experts have labelled the birth rate "catastrophic" and called on the government to act before it's too late.

Liz Allen, a demographer and researcher at the Australian National University, said Australia's total fertility rates showed a "further decline from last year's rock bottom".

"So we're getting into this territory now where we're headed toward a point of no return," she told SBS News.

"We're going further and further into ultra-low fertility rate territory, and once we get to the 1.41, 1.3, 1.2 even, births on average per woman — we cannot come back from that."

Allen said multiple examples show that once a population hits an ultra-low fertility rate, "there is really nothing" that could bring it back up to par.

"Some refer to this continued decline in total fertility rates as a human catastrophe," she said.

What's driving the plummeting birth rate?

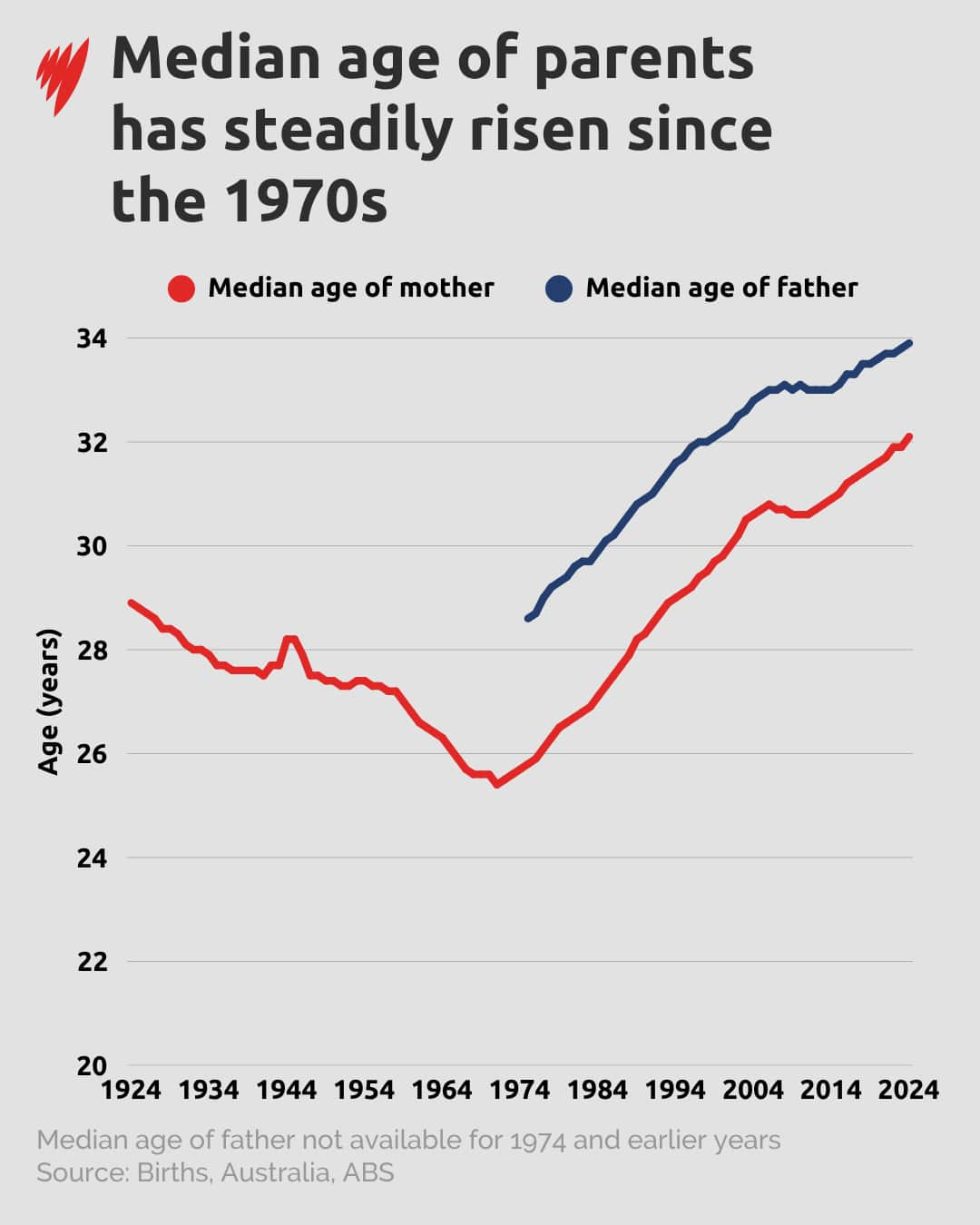

Pelin Akyol, research manager at the e61 Institute, a non-profit economic research centre, said Australia's declining fertility rate was driven by "three factors" — later parenthood, parents having fewer children, and a rising share of people without children.

"The most significant of those is parents having fewer children, leading to smaller average family size," she said in a statement.

Akyol noted that concerns around the cost of raising children and job security had "consistently ranked" as the most important factors in the decision to have a child, for both men and women.

“In recent years, three factors have increased in importance, particularly for young women: The cost of raising children; time and energy for one's career; and availability and affordability of quality child care."

A recent report from the e61 Institute on Australia's declining birth rates found government-funded incentives like the baby bonus, a John Howard-era initiative which provided lump-sum financial payments to encourage an increase in birth rates, could raise fertility for some groups.

But they could not "fully" counter broader demographic trends.

"Looking ahead, policies that support fertility while maintaining or enhancing workforce participation will become increasingly critical," Akyol said.

'Not about selfishness'

The data found that younger women were having fewer children, with fertility rates for women aged 15 to 29 years decreasing.

Allen said that fewer people were able to achieve their desired family size across their lifetime, not because of biological capacity, or what might be perceived as "selfishness" — choosing not to have a child.

"Really, it's because the social obstacles or hurdles to achieving a much-wanted family are insurmountable," she said.

"Things like housing affordability, economic security, gender equality and climate change are all now at this kind of confluence of crises that make it so difficult to really achieve in the world, to thrive.

"Deep at the heart of this is a lack of hope. This fear about tomorrow is so entrenched, and tomorrow doesn't feel certain, so folks are saying, 'We can't possibly bring a child into this.'"

Women aged 30 to 34 years had the highest fertility rate, at 106 babies per 1,000 women, an increase from 105.2 the previous year.

Allen said while it was good this cohort were on the rise, it marked a concerning factor was driving the infertility rate: the age at which women feel they are financially stable enough to have a child is increasing.

"The window of opportunity for having a family is narrow, and it becomes even more narrow with time. So, in other words, the older we are when we start having a family, the fewer children we will have over our life.

"If we think about the trajectory through life, we need to be financially and socially secure, so that means securing ourselves in a career in the labour market, building that ever-growing house deposit and then feeling safe and secure to then start a family," she said.

Women aged 45 to 49 years had the lowest fertility rate with 1.4 babies per 1,000 women, followed by women aged 15 to 19 years at six babies.

Allen noted there were increasing rates of people choosing not to have children, which was good for society, but she wanted to stress there was "a lot going on" preventing people from having "much-wanted children".

"We are undermining the very future of this place because we've made it simply too difficult, or we've removed the necessary supports for people to achieve a much-wanted family."

Allen said Australia's housing affordability crisis needed to be addressed if governments wanted to lift the birth rate.

Gender inequality was another issue that was "holding us back", she said, along with the environment.

"Climate change weighs so enormously, particularly on young people's minds and their fears about tomorrow. We need to address housing, the economy, gender and climate. If we don't tackle these big-ticket items, we are going to be having this conversation year in, year out," she said.

"We're going to get to the point where we say we can't do anything. It's a done deal. We can't reverse this. No baby bonus or lump-sum splash of cash is going to get us out of this mess."

Allen said a "coordinated approach" was needed to make families "doable".

"Because the reality is, at the moment, having a much-wanted child is simply out of the question. It is not practical, it's not doable, and it's a sad indictment on Australia."

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.