GAZIANTEP, Turkey

When Israel started its offensive again Hamas last month, Um Marwan sold her gold wedding ring and bought herself a television.

“I wanted to follow the war,” she said.

Mrs Marwan’s purchase sits glowing in the corner of the tiny, ceiling-less cubicle she has shared with five other women for the past three months. It screens the news from Gaza—and plays the occasional resistance anthem—all day long. Two children, Marwan, 11, and Ashjan, 9, watch avidly from the inch-thick mattresses that overlap one another on the floor. “However bad our circumstances are here, we are sorry for the people there,” Mrs Marwan said.

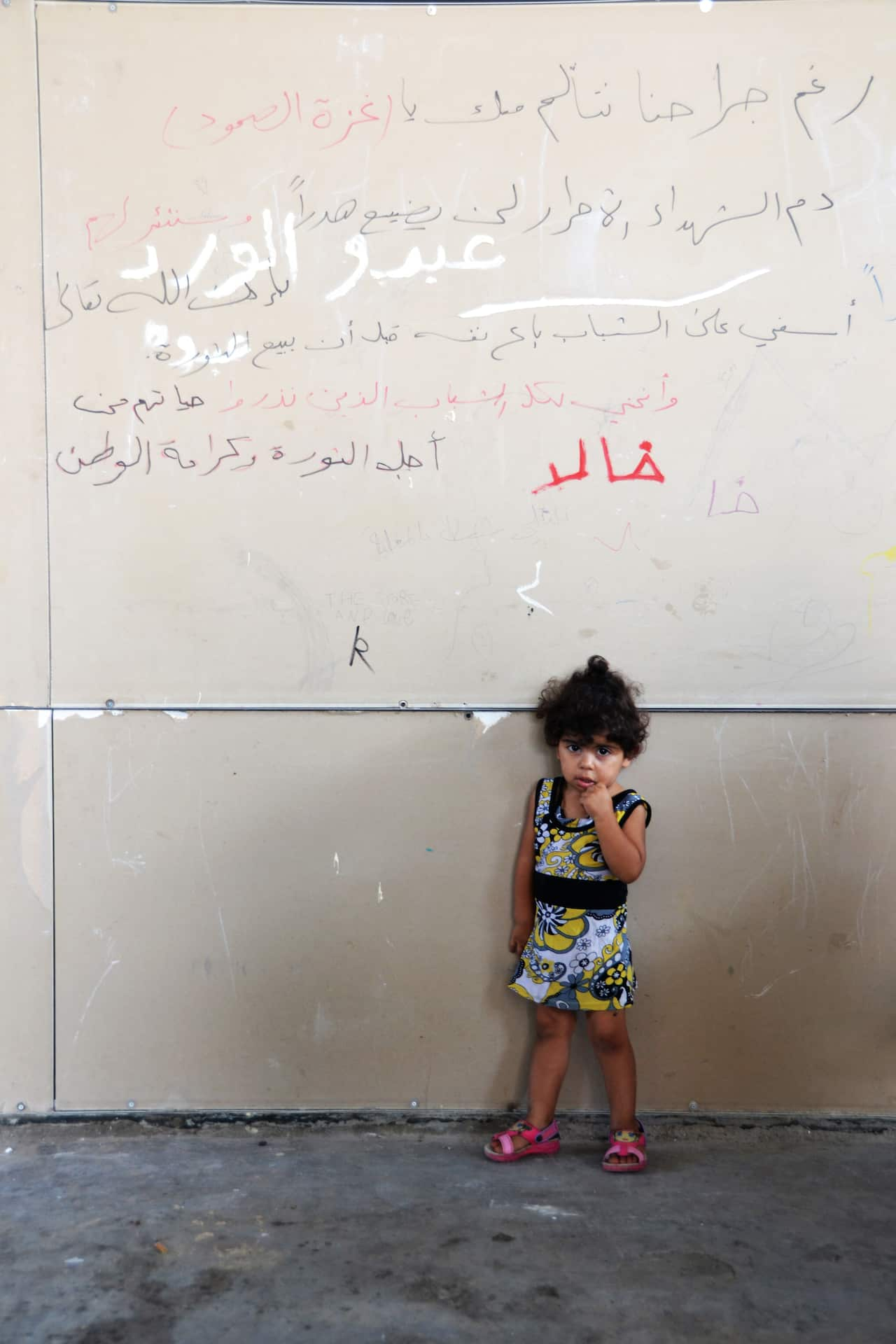

Mrs Marwan, 48, is one of 300 Palestinian refugees—110 of them children—currently living out of a former tissue paper factory half a kilometre from the Turkish-Syrian border and the Öncüpınar refugee camp that was built by the Turkish government two years ago. Established in April by the Syrian Interim Government as a temporary residence for Syrian-based Palestinian refugees who have been displaced by the fighting to the south—refugees twice over—the factory-camp enjoys none of Öncüpınar’s facilities or funding.

“We are going to die without assistance,” Mrs Marwan said. “We don’t have medicine. We have nothing for the children. They have not been to school in three years. The regime shelled all the schools back home.”

“We would prefer to go to Gaza than stay here,” she said. “At least in Gaza, we would be dying on Palestinian land. Here we are only dying.” Mrs Marwan’s determination to follow the plight of Gaza’s Palestinians contrasts starkly with the world’s lack of interest in following that of her and her camp mates. Indeed, Bashar al-Assad’s campaign against Syria’s Palestinian refugee population—estimated at 530,000 before the beginning of the war, two-thirds of whom have since been displaced—has been one of the more under-reported aspects of the conflict.

Mrs Marwan’s determination to follow the plight of Gaza’s Palestinians contrasts starkly with the world’s lack of interest in following that of her and her camp mates. Indeed, Bashar al-Assad’s campaign against Syria’s Palestinian refugee population—estimated at 530,000 before the beginning of the war, two-thirds of whom have since been displaced—has been one of the more under-reported aspects of the conflict.

That campaign has been as ferocious as any the regime has waged in the war. In Syrian Palestinian camps such as Yarmouk, Khan Eshieh, Ein El Tal and Husseiniyeh, rifts between pro- and anti-regime factions have resulted in fierce internecine fighting and provided a cause for external bombardment. Yarmouk alone has seen its population plummet from 180,000 Palestinian refugees to roughly 20,000 since Syrian forces first laid siege to it two years ago. Amnesty International has described the deliberate starvation of the camp’s residents as a war crime.

Everyone at the factory-camp is scarred in some way. An elderly man from Dera’a refugee camp in Syria's south lost three toes and his hearing in an airborne attack. A teenage boy has shrapnel wounds all up his right leg. The younger boy, Marwan, has one smack-bang in the centre of his chest, which he reluctantly allows the adults to show reporters. A toddler’s arm is scarred bright pink from a third-degree burn.

For Ahmad Smair, the new camp’s 27-year-old spokesman, who witnessed the shelling of the Dera’a camp first-hand, the attacks were a brutal wake-up call.

“Israel has been our enemy for decades,” Mr Smair said. “But in Syria we were attacked by a man—a president—who said he was on our side. It was very painful.”

The upside of this pain was knowledge, he said. “We learned the truth about Bashar al-Assad. We learned that he was not interested in defending us. We learned that there is no future for us as Palestinians in Syria.” Everyone’s exodus was slightly different. Mr Smair’s was a seven-day walk through the desert. Those with children took more than twice that time. With Jordan's border closed to Palestinian refugees, Turkey tended to be the goal, even for those coming from as far south as Dera’a.

Everyone’s exodus was slightly different. Mr Smair’s was a seven-day walk through the desert. Those with children took more than twice that time. With Jordan's border closed to Palestinian refugees, Turkey tended to be the goal, even for those coming from as far south as Dera’a.

Diya Abu Mahmoud’s story is particularly harrowing. The 36-year-old street cleaner was arrested last year and spent nine months in a regime prison under suspicion of being a sniper. The first three months saw him tortured on a daily basis.

“They were the hardest months of my life,” he said. “I wished for death 100 times a day. I tried to cut my wrists with my fingernails.”

Eventually, Mr Mahmoud’s Alawite uncles-in-law intervened and he was released. He made his way to the Jordanian border, but was refused entry on the grounds that he was Palestinian. “I was close to dying and they turned me away,” he said.

He spent more than two weeks trudging north towards Turkey, taking long detours through the desert around Syrian government and Free Syrian Army (FSA) checkpoints and Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) brigades. “I received the best treatment from ISIS,” he said. “Others say they are harsh and terrible, but they were very kind to me.” He finally reached Turkey in April.

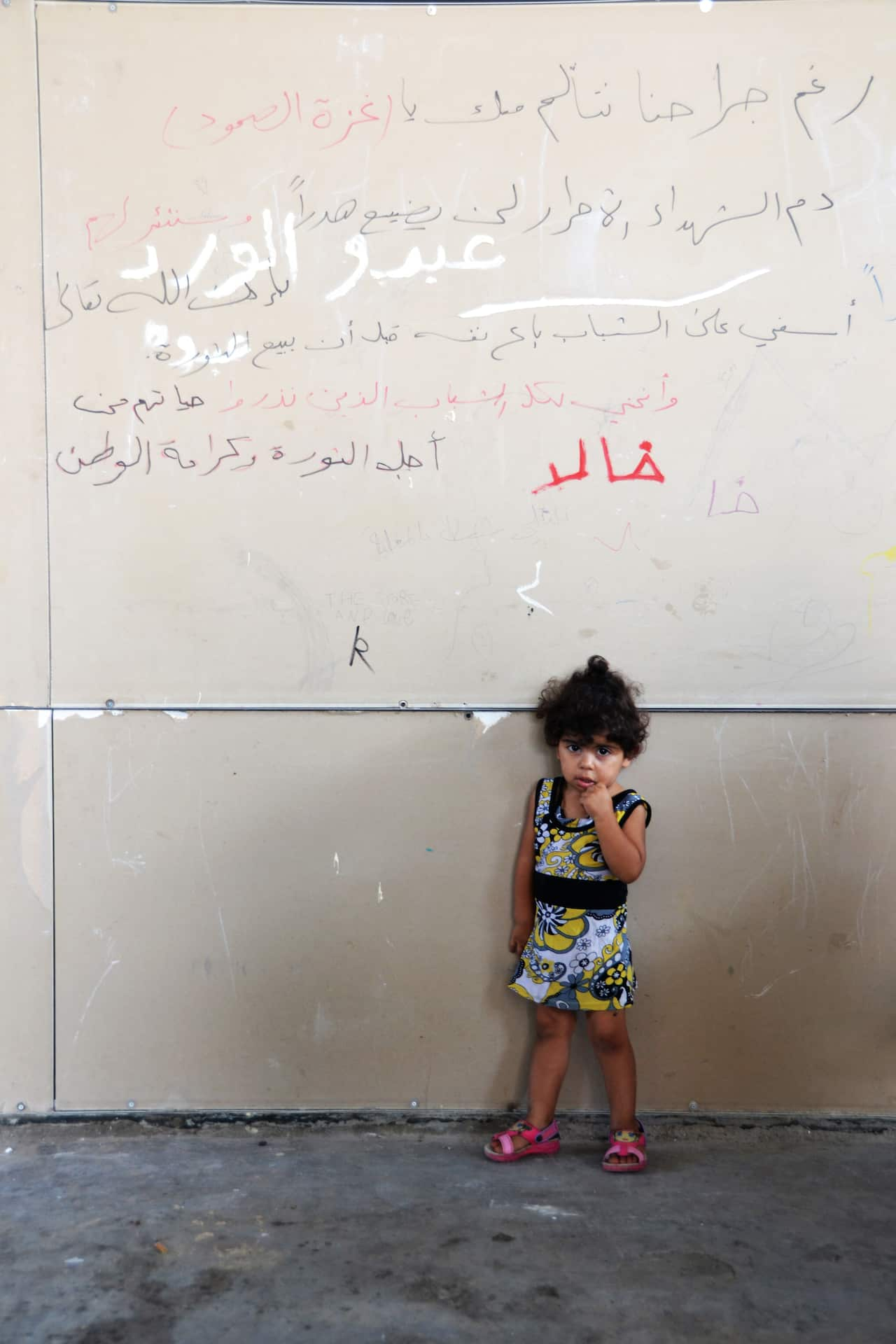

The stretch of road that leads from the Turkish town of Kilis to Öncüpınar is lined with trucks that have nowhere to go. A few men sit smoking cigarettes on the front porch, watching the vehicles as though they were actually passing by. Out the back, the tall, white doors of the factory have recently been painted. On the left door, the Palestinian flag. On the right, the Turkish one.

“We thank the Turkish people for receiving us,” Mrs Marwan said. “They are better than [Jordan’s] King Abdullah, allowing us to die as we wait on his border.”

“The management here is doing its best with what it has,” she said. “But unlike the Syrian camps, Palestinian refugees don’t really have anyone to support them.”

This may have to change, though, and soon. Mr Smair said the camp was already preparing for an influx of Palestinian refugees for when the siege of Yarmouk is eventually lifted.

“We have approached the Turkish government about helping us to establish a proper camp like Öncüpınar,” he said. “These tents are fine for summer, but we are going to need containers in winter.” (The Turkish government has previously provided insulated containers to a number of Syrian refugee camps within its borders.)

But Mr Smair ultimatey thinks that it will eventually be time for him and his camp mates to move on anyway.

“We escaped Palestine. We have now escaped Syria. That is what it means to be Palestinian,” he said. “We don’t have a land and we are refused everywhere. We must be prepared to escape again.”

Share