In the driveway of a suburban home in Wodonga, in northern Victoria, a small grey hatchback with a cracked tail-light and scratches along the bumper is being inspected.

Kimararungu Nelson Budederi and Runezerwa Masange, known as Nelson and Masange in the local Congolese community, are examining tyres, safety features and an additional brake and accelerator on the passenger side.

From the outset, the car is unremarkable.

But in reality, it carries the hopes of hundreds of Congolese refugees living along the Victorian-New South Wales border.

The dual drive vehicle is an essential component in the launch of an in-language driver education program spearheaded by Nelson and Masange, with the aim, Masange says, of changing the lives of regional refugees.

“We have changed their country but we have not changed their future. What we stand for is to try and help those people change their futures.”

Nelson and Masange were among the first Congolese refugees to arrive in Albury-Wodonga after the border region was identified as a settlement option for asylum seekers from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Nelson says with asylum comes a renewed hope for freedom to those escaping violence and persecution - but many regional refugees continue to live constrained and isolated in their new homes without a driver’s licence.

“It’s more than a form of ID here in Australia, it’s not easy, people are struggling here with the very basics of life.”

He says without transport, many new arrivals struggle to secure a job, get access to school or TAFE and even get groceries from the shop to home.

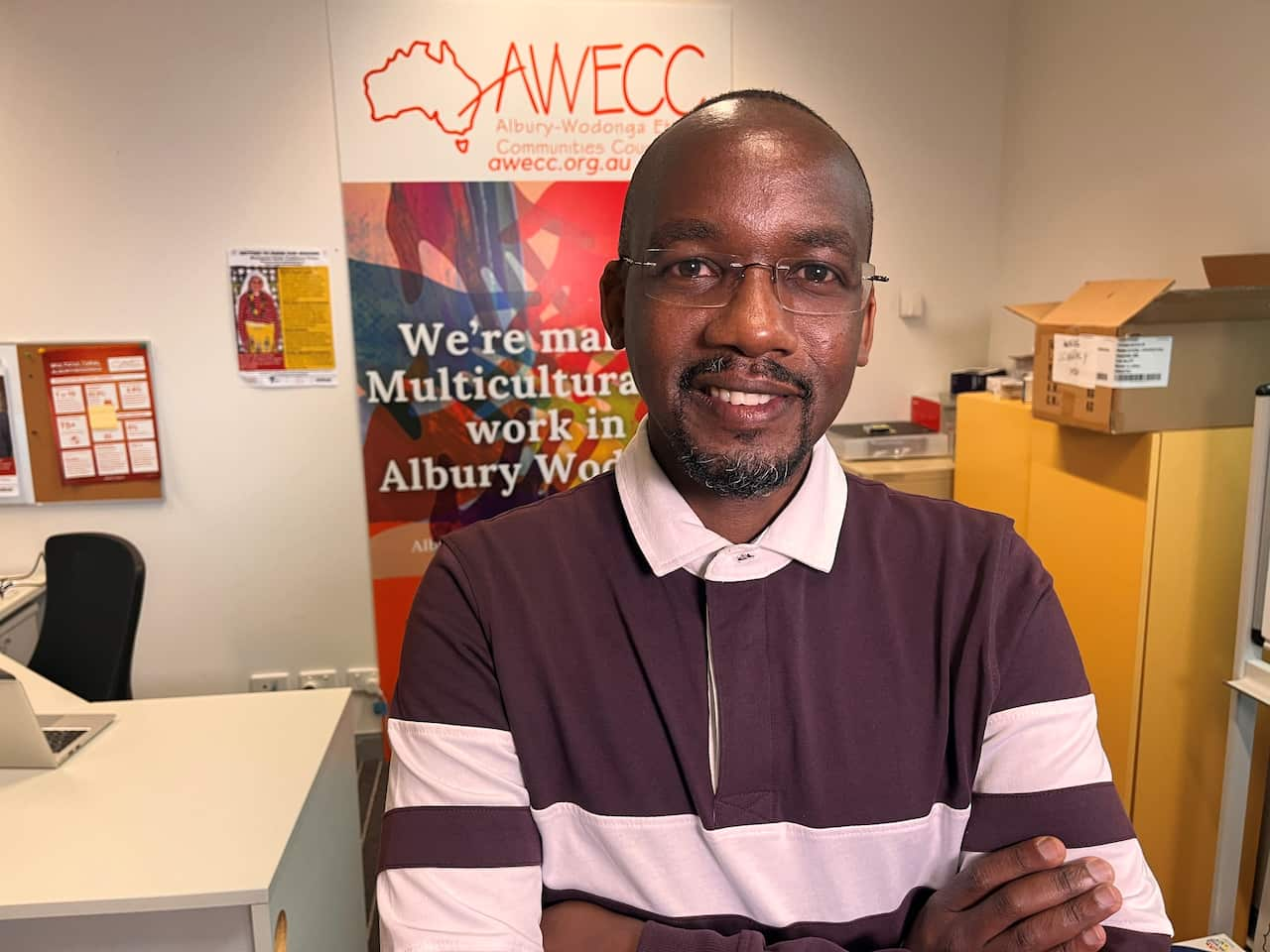

Community advocate for the Albury-Wodonga Ethnic Communities Council Richard Ogetii says he knows several women who wake at dawn to be the first at the supermarket, so they can push their loaded shopping trolleys home without being seen.

“She has to wake up very early in the morning, before people are up and about, to be the first person at the supermarket because of the embarrassment of pushing the trolley along the streets.”

At first, he says, new arrivals ask neighbours or other community members for help in getting around, but soon feel uneasy about requesting too many favours.

Mr Ogetii says many of the border region's new arrivals have spent years, if not decades in refugee camps, arriving in Australia with limited English and no driving experience. He says they need a tailored, in-language approach to catch up.

“We take it for granted that being able to drive is easy or that everyone should be able to drive, but without support it becomes very difficult and those people somehow end up being isolated.”

Albury-Wodonga’s first in-language driving program

The Murray Valley Sanctuary Refugee Group offers subsidies for refugees wanting to pay for driving lessons, an expense that can cost hundreds of dollars.

The group’s Penny Vine says settlement services recognised early on that the lack of a driver’s licence had become a barrier to integration into the local community.

“When you’ve got a family of 10, $360 for six lessons is not a reasonable expense, but it’s essential.”

She says even when professional lessons can be budgeted, language still remains a major obstacle.

“Often the translator is one of the children in the family, and they don’t know how to drive either.”

The group has now signed a memorandum of understanding with Nelson and Masange to provide the dual drive car they need to get Albury-Wodonga’s first in-language driving program up and running.

Nelson says while they had been attempting to provide lessons in Swahili, French and several other languages using their own cars, lessons can be dangerous without a brake and accelerator on the passenger side.

“We’ve been trying to help the community using our car but it’s not safe, but with this we will be able to do more.”

The program still in its infancy has attracted lots of interest, with Congolese refugees issuing requests for lessons daily.

Why getting a licence matters

Rain, hail or shine, Nyakiza Nyandebwa and daughter Bierro Nyamahoro have no option but to walk to get around Wodonga.

Nyakiza says being able to drive a car would be life-changing for her family.

“I am a single mum. We have to walk to go to school, in winter, cold and all weather. Getting a licence would be a victory. I could drive to school, find work and drive to the shops.”

They arrived in Australia in 2019 after fleeing the Democratic Republic of Congo. Neither had ever driven a car, and Bierro says they’re now finding some opportunities in the border town that are out of their reach.

“If I could get a licence I could help my mum, and when I finish school I could get a job and become independent.”

There are train stations at Albury and Wodonga, but there's no rail service to the outer suburbs. There are also no trams and a limited bus network that locals call unreliable.

Roberta Baker from the Albury-Wodonga Ethnic Communities Council says through her work, she knows many new arrivals who reach the final stages in the job interview process only to fall at the last hurdle when it comes to being able to drive.

“What we find is that the geographical distance between Albury and Wodonga, with a river down the middle which is about five kilometres, if you live in one town and have a job prospect in the other you have to be able to drive there.”

Richard Ogetii says for refugees, a driver’s licence is more than a practicality, it’s a symbol of belonging and taking a place within Australian society.

“Being able to drive means more than just having a driver’s licence. For other people it means getting a job, being independent and being able to live with dignity.”

Masange says when he fled violence in the DRC in 2008, he spent five years in Kenya losing all hope for a better life.

Today, driving the streets of Wodonga, he says life is a highway.

“Now I can dream bigger, I can be someone in the future.”

He and Nelson are now determined to help others find their freedom behind the wheel of a car.

Would you like to share your story with SBS News? Email yourstory@sbs.com.au