The Albanese government is once again defending its ability to construct homes and keep up with increased demand.

Reserve Bank of Australia governor Michele Bullock this week skirted questions about offsetting rising house prices by cutting interest rates, stating she was in the business of targeting inflation as she delivered another rate hold.

Bullock did admit that, despite government efforts to address a supply hole, she can't see a way through the problem in the next two years.

"You are seeing some action on that, but it's going to be slow to work its way through," she told reporters.

"I'm not confident it's going to make any impact in the next two years."

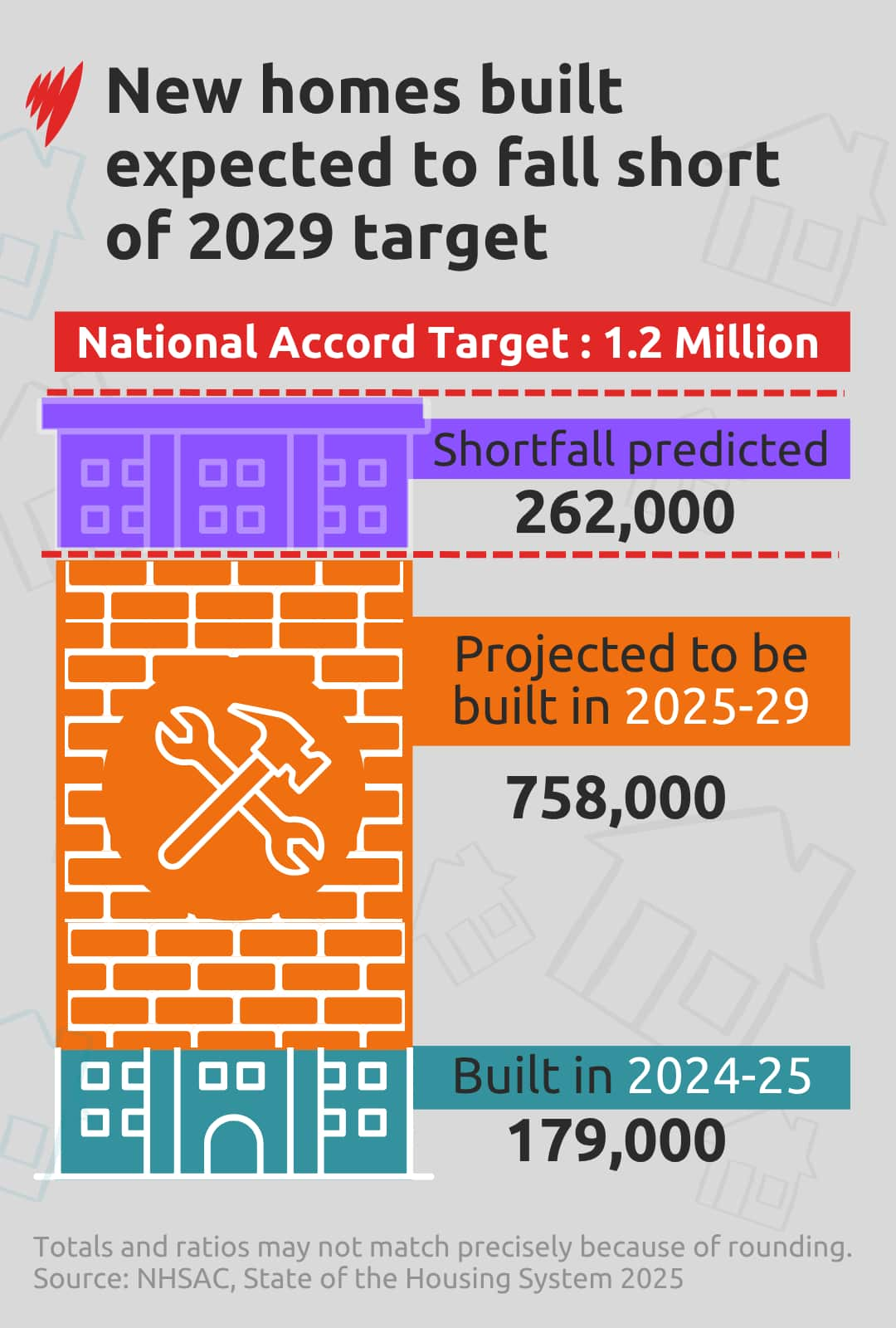

Ahead of the May federal election, Labor campaigned on a $43 billion housing agenda, which includes building 1.2 million homes by 2029 to achieve the National Accord Target, with frontbenchers proudly labelling it "ambitious".

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said Bullock's remarks were "common sense" as it "takes time to build a home", promising an "acceleration" of building in later years.

A spokesperson for Housing Minister Clare O'Neil said on Tuesday: "Homes don’t get built overnight, but we are seeing a real turnaround in home building right across the country."

On track to build 1.2 million homes? Not quite

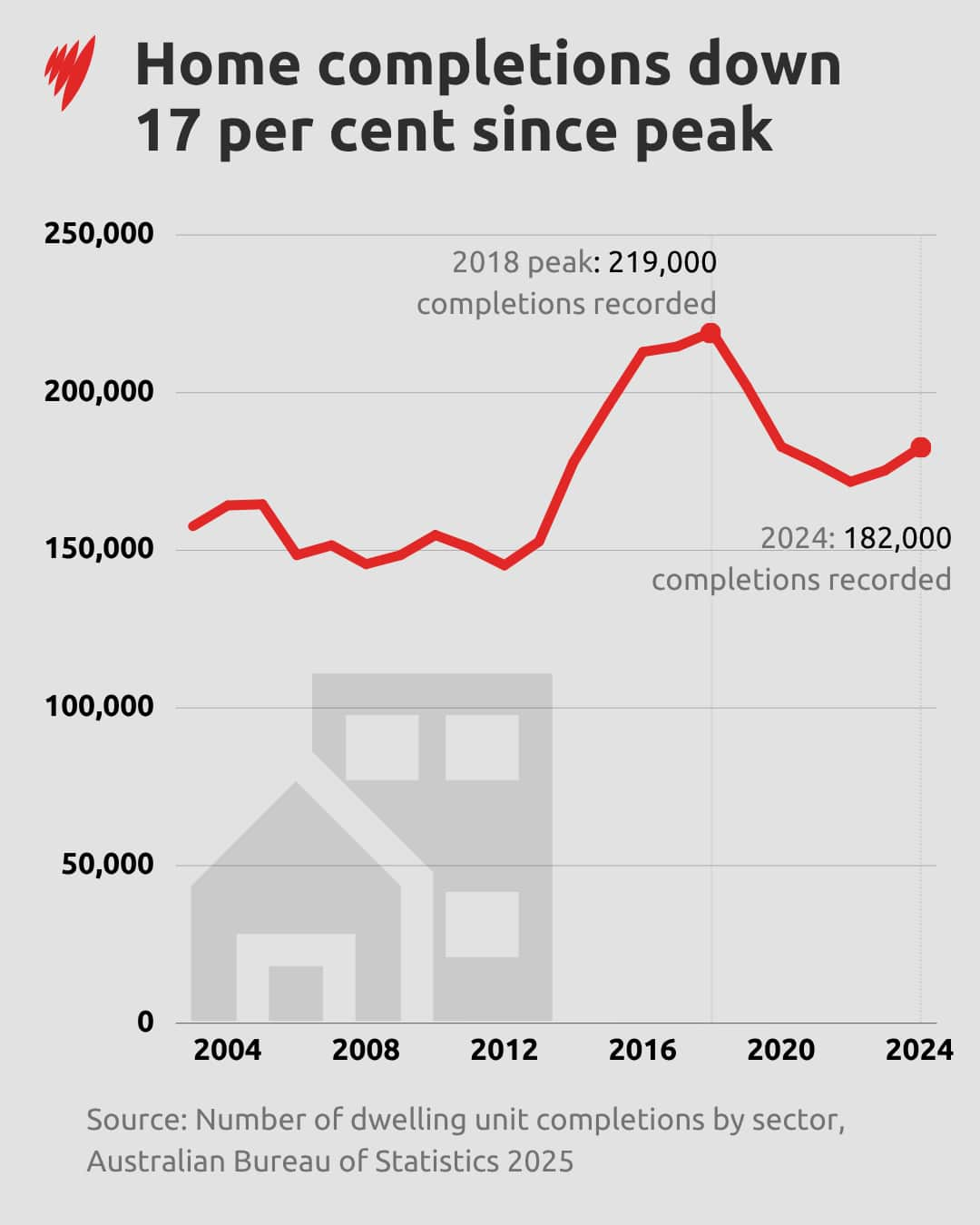

Australia would need to boost construction to unprecedented levels to catch up and meet its 1.2 million target, surpassing its completion peak of 219,285 dwellings in 2018.

To achieve the target, 60,000 homes need to be built every quarter. In 2024, roughly 45,000 houses and units were built each quarter — a total of 181,789, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

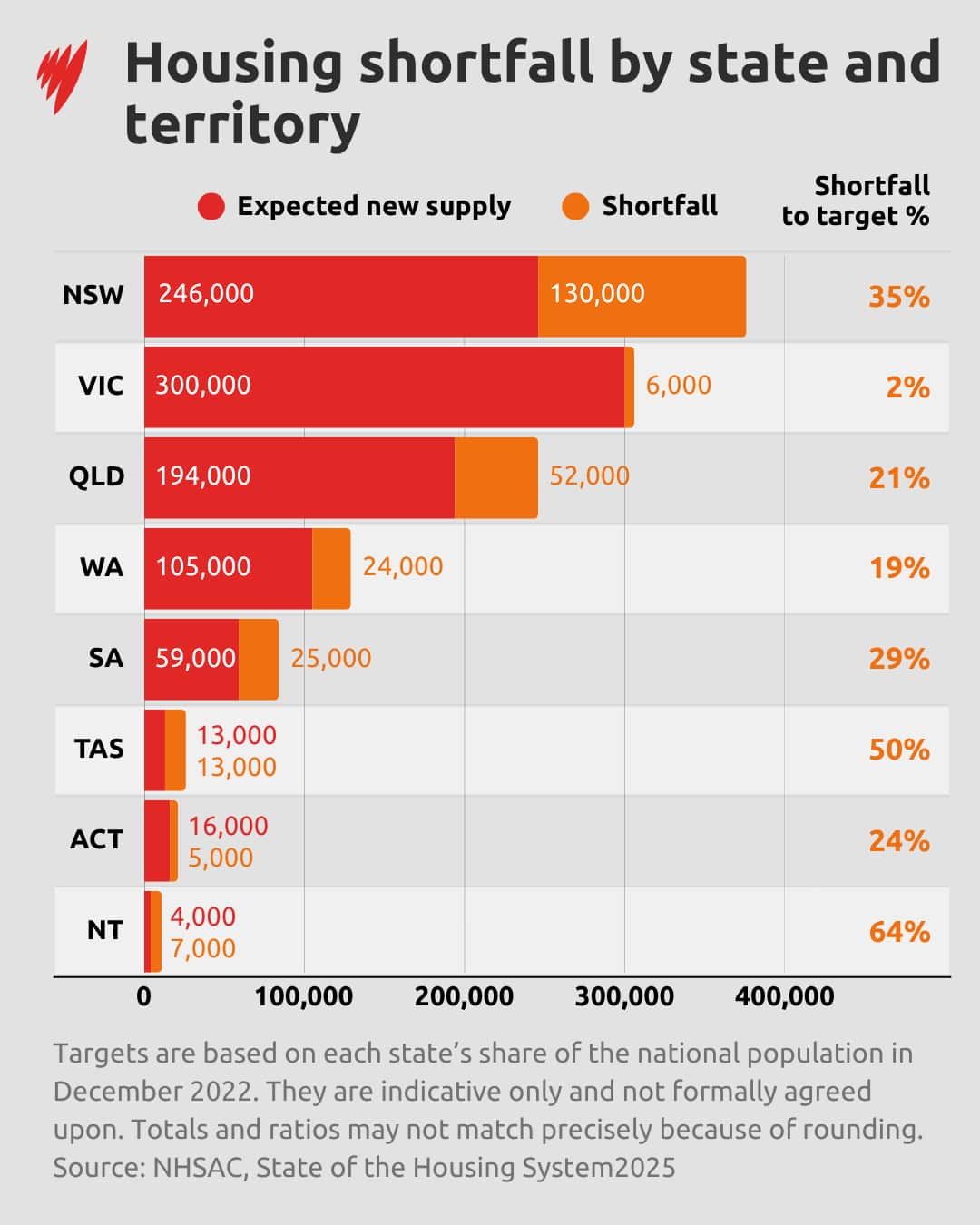

In May, a report by the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council declared that at the current pace, the government would fall 262,000 homes short.

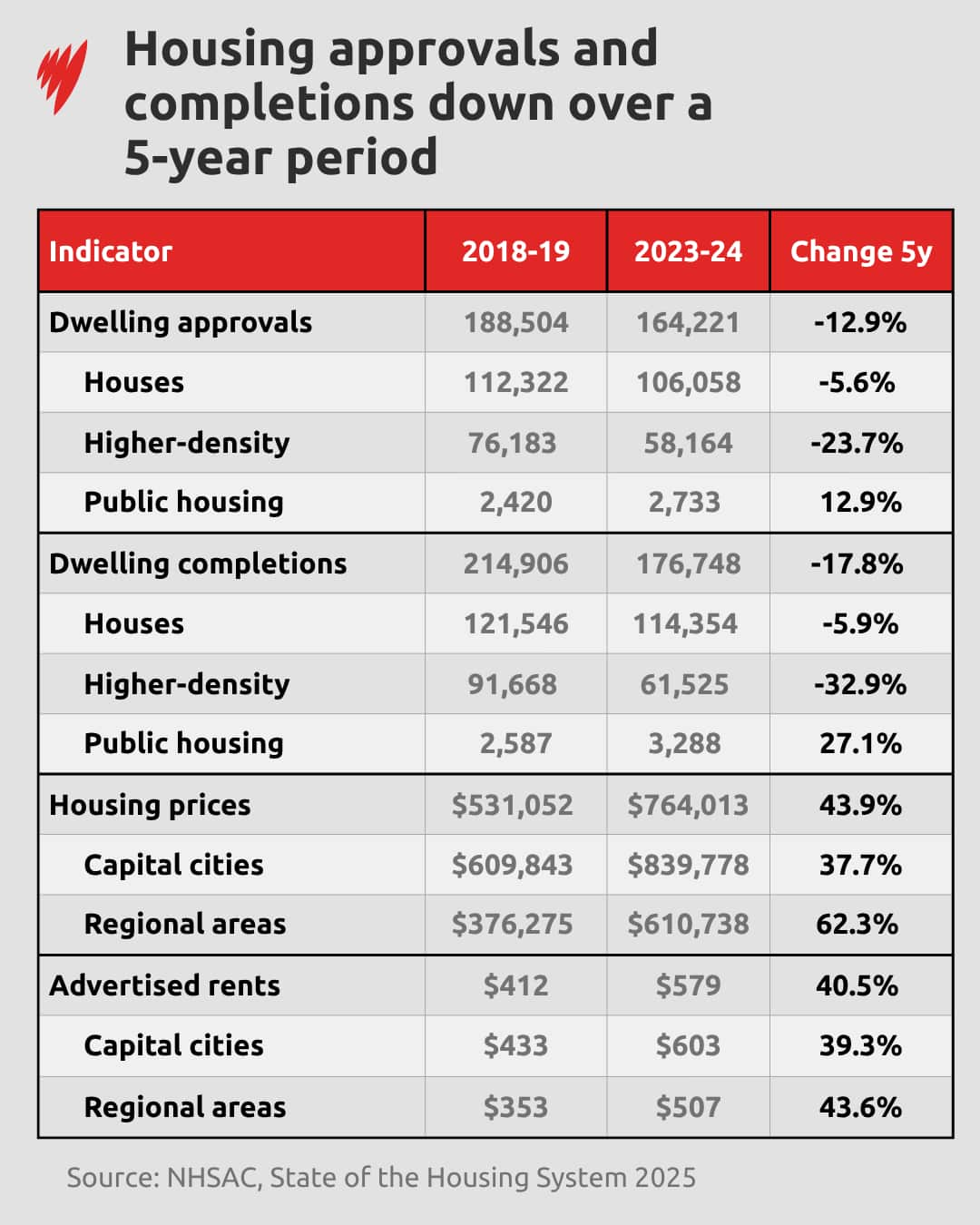

Analysing market changes over five years, it found that while housing prices and rents had soared since 2018-19, approval and completion rates were lagging.

The government had completed 17.8 per cent fewer homes in 2023-24 than five years earlier, with a lack of building of higher-density buildings like apartments particularly acute.

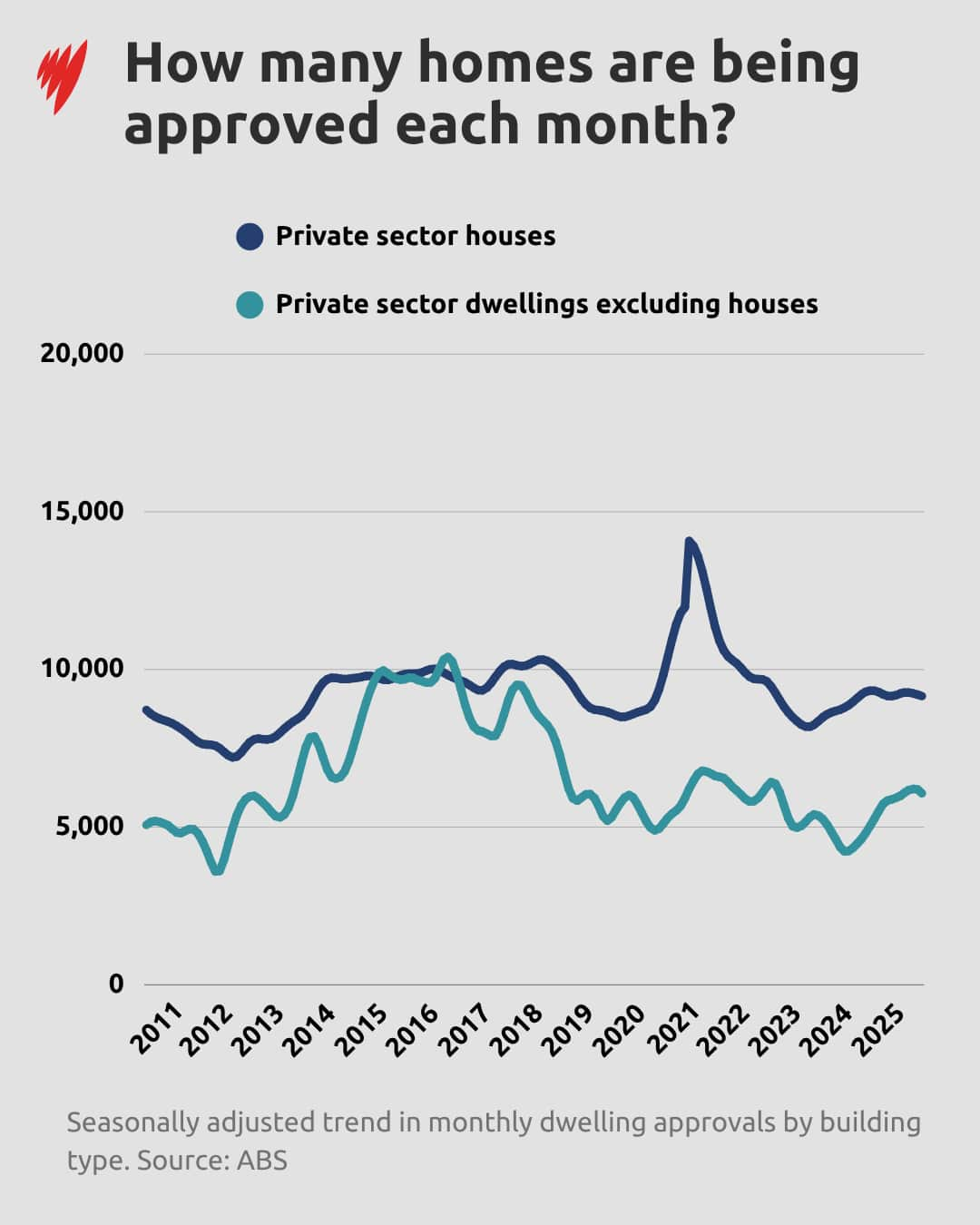

Building approvals had also been on the decline. However, the latest ABS data, released at the end of September, shows the number of units approved for construction was up 3 per cent over 12 months, despite being down 6 per cent in August.

Master Builders Australia estimates one million homes will be built by 2029, also falling short, but CEO Denita Wawn says under the right conditions, the gap can be bridged.

"We're falling short of the stretch target," she told SBS News.

"The reason for that really is to do with the lack of skilled people to undertake that work, an inadequate amount of build-ready land, and delays, meaning that there are escalating costs."

What can the government do to catch up?

Wawn acknowledges that for "every year we have a shortfall, the forward years keep on increasing beyond 240,000" homes needed a year to achieve the target.

However, she believes the government can speed up construction by fast-tracking planning, focusing on skilled migration to attract the roughly 100,000 extra workers needed, and retraining people who didn't complete apprenticeships.

Economist Saul Eslake told SBS News state and local government needed to address zoning and planning regulations, with prospective buyers copping high charges imposed on developers, but conceded there's "no silver bullet".

"Accessing greenfield sites [undeveloped land] because of poor planning or public transport … has added to the cost and to the time taken to construct new housing," he said.

"There's a whole of factors involved, and while boosting supply is important, there's no magic bullet that will enable it to happen quickly."

He also suggested productivity declines over 25 years could be boosted by innovation, looking to the United States, where prefabricated or modular housing is helping build cheaper homes.

Property Council chief executive Mike Zorbas said even if 1.2 million homes aren't built, the government's target "remains the best way to keep state governments incentivised and accountable."

"Rising construction costs, labour shortages and poor on-site productivity are putting pressure on the industry’s capacity to deliver new housing," he said.

"We’re currently behind our targets, but this shouldn’t make us throw up our hands and give up. Instead of conceding defeat, we should intensify our efforts and remain focused on achieving our housing targets."

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.