In the last few years, Uber has gone through a life cycle that once took successful companies decades to complete—from start-up to upstart, from pushy disruptor to pushy behemoth, from iPhone button to cultural icon. Uber’s executives don’t like to associate themselves with the “sharing economy,” the smattering of firms that allow average Joes to sell access to their fallow goods and services (rent my empty home on Airbnb, buy my open 3 p.m. hour on TaskRabbit). The company’s ambitions, it says, are grander. But for now, the vast majority of drivers are behind the wheel of their own car. “Sharing” is, to be quite literal, the majority business of Uber.

This puts Uber squarely in the crosshairs of a debate about what exactly this peer-to-peer economy means for the future of the economy. (Like all discussions that include the term “future of the economy,” this can amount to little more than rounding up some very recent developments and projecting forward 10 years with jaunty confidence.) Are these new companies creating value from nothing, or destroying the value of the formal economy? Are they inventing new, flexible ways for underemployed Americans to work, or are they contributing to the destruction of full-time jobs?

The typical Uber driver is a college-educated man, married with kids, who is supplementing a full- or part-time job with about 15 hours of driving a week, logging 20 to 30 trips, and earning an extra $300 to $400 a week (before factoring in the cost of gas and upkeep). That’s according to a new paper by Alan Krueger, the eminent Princeton economist who served as chairman of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, working with Uber’s head of policy research, Jonathan Hall. Krueger and Hall based their research on both Uber's data and an online survey of 600 Uber drivers in 20 markets, including New York, Washington, and San Francisco.

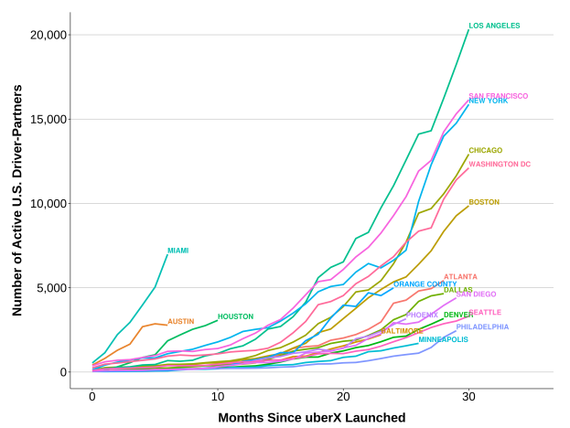

The best way to review the paper's factoids is to flip through the pretty pictures. Uber's growth exploded in late 2013 thanks to the rise of its cheaper uberX program, which now accounts for more than 80 percent of its drivers. The largest market of uberX drivers is Los Angeles. The fastest-growing are new entrants Miami and Austin.

UberX's Conquests: City-by-City Uber/Krueger

Uber/Krueger

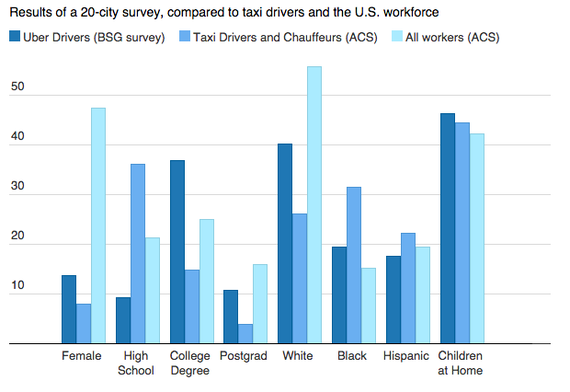

According to the online survey, Uber drivers are almost 90 percent men, which is still more female-heavy than taxi drivers. They're also more diverse (defined as: less white) and more college-educated than the general workforce, but similar in age and likelihood to have a kid. In other words, Uber drivers are a fairly perfect representative sample of a typical U.S. metro area workforce.

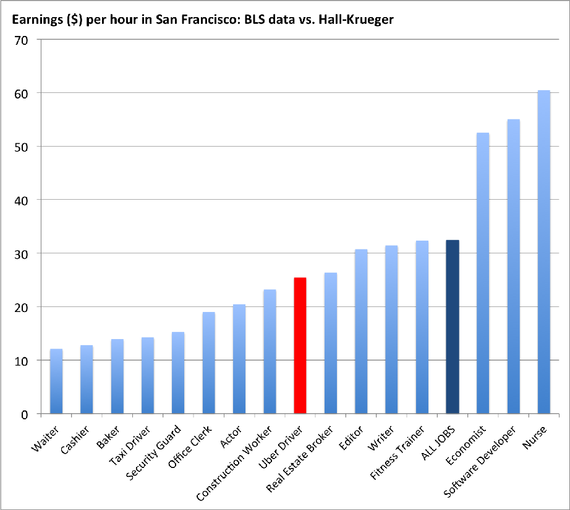

In large cities, uberX drivers report earning between $15 (Chicago) and $25 (San Francisco) per hour before factoring in the cost of gas. How does that stack up against other jobs?

To give you a rough, rough sense—really, I can't stress enough the roughness of the sense, since I'm comparing figures from separate surveys and not including driving costs—I've graphed a comparison of self-reported hourly earnings of Uber drivers in San Francisco against the hourly earnings of other San Francisco occupations from the Bureau of Labor Statistics' occupational employment stats. At least in this comparison (rough!), driving with Uber is a more efficient way to make money than the most common jobs in America, cashiers and retail salespeople, or being a taxi driver, a baker, or a construction worker. It's still not as lucrative as the average San Francisco occupation.

The fact that Uber drivers make more than cabbies and clerks doesn't yet tell us about how it fits into workers' lives. Is Uber about desperation, or is it about flexibility?

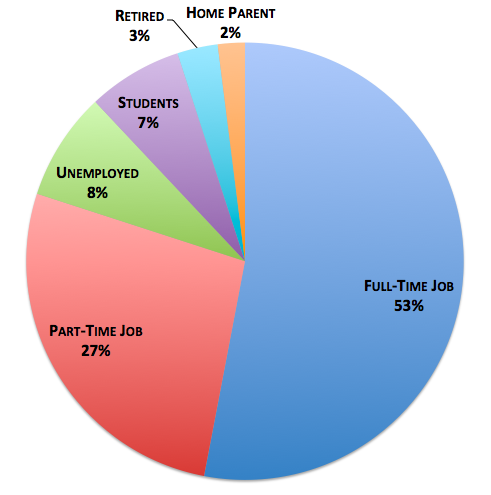

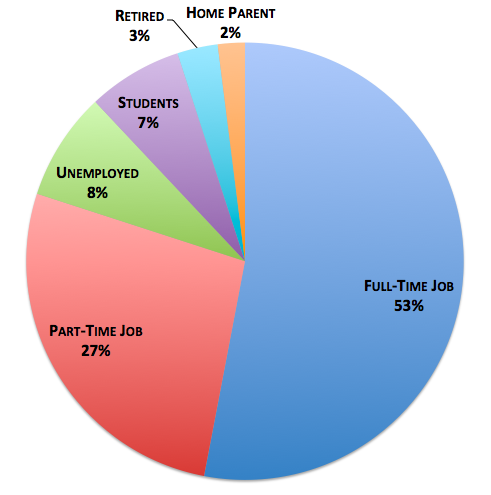

Four in five Uber drivers were employed before they started driving. Most of that group was working full-time. Rather surprisingly, only eight percent of the Uber drivers said they were unemployed before joining Uber, a rate only slightly above the official jobless rate, which averaged about 6 percent throughout 2014. So, Uber drivers aren't turning their cars into jobs because they can't find work. They're joining Uber because they can't find enough work. (Once again, this suggests that Uber drivers are representative of the typical metro-area workforce.)

Before Uber: 80 Percent Working Full- or Part-Time Jobs Uber/Krueger

Uber/Krueger

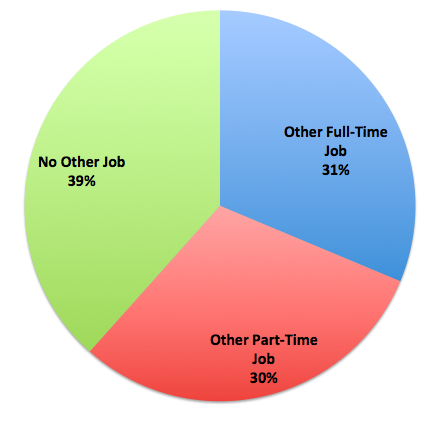

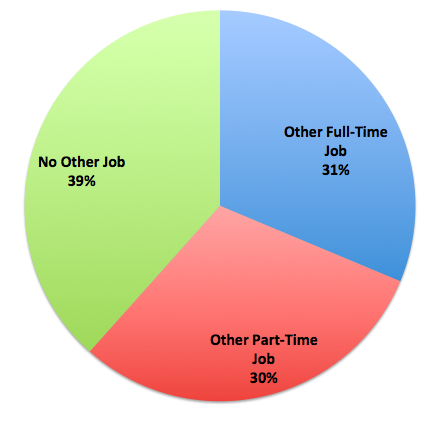

Uber is not a full-time occupation. Ninety percent of online respondents said they drive fewer than 35 hours a week. Once they join Uber, most drivers are keeping their job outside of the car. But the share of drivers with full-time jobs outside of the car is significantly lower than in the last graph. About 40 percent of drivers say Uber is their only job. An equal share say they make more money from their other job.

With Uber: 61 Percent Also Working Full- or Part-Time Jobs Uber/Krueger

Uber/Krueger

In the debate over Uber, economists have wondered whether it's creating a freelance economy or merely empowering the freelance economy that already exists. The most annoying possible answer to these debates is the truth lives somewhere in the middle, but, well, sorry, the truth really appears to live somewhere in the middle. Uber drivers, who are often men with kids, look like a representative sample of the metro-area labor force, just more likely to be employed part-time. To make more money for themselves and their family, they're turning their cars into jobs. Once they join Uber, they seem less likely to work full-time. I say seem because a survey without control groups can't prove anything even close to causation. So, to use a more cautious word than conclude, I propose that Uber is both drawing the freelance labor force and making men with full-time jobs more likely to move toward a life of part-time work and gigs.

It's easy to exaggerate the growth of the part-time economy but equally easy to underestimate it. There is no evidence from official government numbers that part-time work is growing today. But it is possible that the official figures are missing the quiet rumbling of a new religion of work, where young workers in major cities are combining gigs, jobs, and downtime Uber lifts in such a way that makes it difficult for the Bureau to account for the demise of the traditional office job.

About 160,000 drivers have fired up Uber on their phone since 2012. That's less than one month's net job creation. It's about 0.1 percent of the workforce. It is a rounding error. Then again, two years ago, Uber itself was a rounding error on the urban-transportation map. Transforming the marginal into the mainstream at a breakneck speed—it seems to be the Uber way.

Share