Australians should look beyond anti-vaxxers in Byron Bay for the biggest challenge to improving immunisation, according to vaccination experts in light of the latest national data, released today.

Instead, it’s the tens of thousands of under-vaccinated children living in close proximity in Australia’s cities whose parents - despite supporting immunisation - face financial, transport or simply time-related obstacles and have let immunisation slip down their family's to-do list, that need to be prioritised.

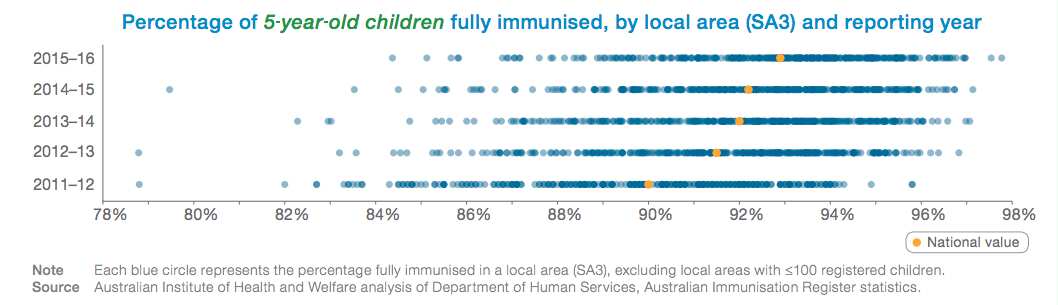

The latest national vaccination snapshot from the Institute of Health and Welfare, based on records in the national immunisation register, shows national vaccination rates improved by between one and two percentage points at each age level measured - one, two and five years - between 2014-15 and 2015-16.

The period of the report covers the first six months of the government's 'no jab no pay' policy that removed some exemptions from the immunisation requirements in child welfare payments to encourage parents to vaccinate their children.

Associate Professor Julie Leask, from the Sydney Nursing School at the University of Sydney, argued it was too early to judge how successful 'no jab no pay' has been from this aggregated data, given it covered only half a year of implementation.

The report also highlighted that 90 per cent of five-year-olds are fully immunised in an increasing number of local areas - 282 of the 325 designated areas in the country, up from 174 in 2011-12.

Some regions continue to demonstrate poor performance, particularly the well-known anti-vaccination hotspot on the New South Wales north coast around Byron Bay, where 84.4 per cent of five-year-olds are fully immunised, and 80.8 per cent of two-year-olds.

Professor Leask said, rather than focus on these outliers, more should be made of the need to vaccinate tens of thousands of children in suburban areas where infectious disease outbreaks are more likely given the close proximity of residents and the higher numbers of incoming travellers.

"Sure, there are these areas that have the low rates, but then you’ve got these big populations of under-vaccinated kids getting less attention,” she said.

“In these areas the general vaccination rates might be okay, but to improve them to 95 per cent, you actually need to get a whole lot of kids vaccinated in those regions and up to date.”

Chief health officers around the country agreed in 2014 to the national target of 95 per cent of all children fully immunised as a way of reducing the spread of vaccine-preventable diseases like measles.

Sydney’s south-western suburbs were affected by a measles outbreak this year in which more than 20 people contracted the disease from a single returned traveller from Bali.

Five of the top 10 areas in the country ranked by the number of under-vaccinated one-year-olds were in western Sydney, even though all are above or just below 90 per cent fully vaccinated rates.

“The regions that rank as the top 10 for the highest numbers of under-vaccinated kids are areas with more highly mobile populations, and are more likely to have children born overseas who need to catch up with the Australia’s vaccination schedule,” Professor Leask said.

Dr Shopna Bag, Manager of Communicable Diseases at Western Sydney Public Health Unit, said children in the area may not be up to date for a wide variety of reasons, including different cultural practices around doctor visits, disruption to vaccination schedules caused by migration, access to medical services, as well as simply struggles of busy families.

"Sometimes having to go to school drop-off, to after school activities, to then book into a GP where you might have to wait a long period - it just becomes something that can be too hard at times,” she said.

The New South Wales government has provided a drop-in clinic near Auburn train station to aid busy parents as part of what Dr Bag described as a "multi-pronged approach” to improving immunisation in her area.

"It might be facilitating and strengthening medical practitioners through the primary health network and the Public Health Units, or through education," she said.

"But it's also seeing what people's needs are.”

Although states typically manage and fund vaccination programs, the federal government announced earlier this year $14 million in funding over the next four years to provide free vaccinations to teenagers who have fallen behind schedule, and another $6 million for education campaigns in communities with low immunisation levels.

Approximately 72,000 children of ages one, two and five combined remain under-vaccinated, including more than 21,000 one-year-olds.