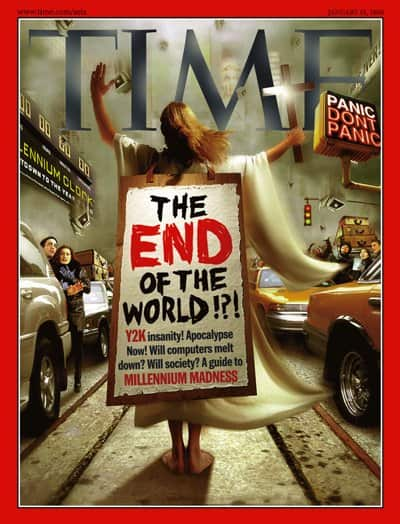

As the world celebrated the end of the century and the start of a new millennium, Peter Costello didn’t party like it was 1999.

Instead, Australia’s treasurer was waiting to see if the dreaded Y2K bug would cause havoc with computer systems having to deal with dates beyond 31 December 1999.

“The first of January would hit Australia first, before it hit Europe and America,'' the former deputy Liberal leader told SBS News. “And so, I was getting updates from midnight on.”

Cabinet papers from the time - released on Tuesday by the National Archives - reveal the returned Howard government took the Y2K risk very seriously.

Then foreign minister Alexander Downer warned: “We judge that high levels of Y2K-related difficulties are likely to occur through most of Asia and Africa, as well as areas of central Europe, South America and the Pacific,” with estimations “30-50 per cent of companies and government agencies worldwide are likely to experience at least one mission-critical system failure” wiping as much as $3 trillion from the global economy.

There were also fears of “significant short-term security problems” in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea.

“All quiet? All quiet? Still all quiet?” Mr Costello recalled of telephone conversations with the Y2K response centre at the time.

“Phew, we’ve made it.”

Immigration cuts

The millennium bug did impact Australia though, just not in the ways some had feared.

Immigration and multicultural affairs minister Philip Ruddock complained his department’s budget had been “savagely reduced by the significant investment required to address the year 2000 IT date problem,” the cabinet papers reveal.

The minister was blunt about the impact: “I can not respond to increasing community pressure for additional grants to meet settlement needs in areas that are proving sensitive”.

To fill the budget black hole, cabinet backed his proposal to introduce a $50 fee for each non-Electronic Travel Authority (ETA) short-term visa issued to those coming to Australia, estimated to generate $160 million over four years, noting “these charges will impact on applicants from overseas, not Australian taxpayers”.

Mr Ruddock warned of “an increasing assault on our border” and “a growing number of unauthorised air arrivals,” urging the coalition to transition Australia’s migration system “from one that was increasingly focused on family entry to one focused on skill”.

Immigration fell from 83,000 to 68,000 and cabinet agreed “that an explicit population policy not be developed”.

“It was a time when government was on a tight leash,” Mr Costello said.

“We were fighting any proposals for new spending because although the budget was in surplus, it was a tiny little surplus.”

Visa character checks

Mr Ruddock controversially secured cabinet approval to “improve” protections for information gathered by Australia’s intelligence agencies which immigration officials relied on to assess visa applicants.

“While protected information may be used by the minister as a basis for a decision to refuse or cancel a visa ... this information cannot easily be kept from legal counsel representing the parties in a court of law if the matter is appealed”, he told cabinet.

“Discussions with relevant agencies have indicated that detailed intelligence information will only be provided to my department if it is protected”.

Cabinet agreed on steps denying visa applicants access to the evidence used against them as well as a fundamental change to how 'character checking measures' were applied.

“Currently the onus of proof rests with the government to establish that the visa applicant or holder is not of good character. I propose that the visa applicant, or visa holder, should have the onus of satisfying the minister that they are of good character where a refusal of cancellation decision may be taken.”

Cabinet historian Paul Strangio said the release of such information in the cabinet papers provides “interesting inklings of the way that immigration and issues around it [were] being increasingly seen through a security prism at that time”.

Sydney 2000 and Australia’s Indigenous peoples

Another key focus of the government from the time was the 2000 Olympic Games.

Having poured more than $500 million into the Sydney Games, the government was extremely concerned about how the world would view Australia during the competition.

Cabinet warned that “unless the international media are appropriately handled and serviced … major damage can be done to the reputation of a city and nation”.

Minister for sport Andrew Thompson told colleagues “there is no doubt that many overseas media will be receptive to protest actions by Indigenous and environmental groups, advocates for the homeless and other disaffected groups,” stressing the need for “a strong emphasis on the positive efforts the government is making in these areas.”

Australia’s embassies and high commissions were also instructed to “monitor” and “counter, where necessary” negative international reporting on the Games.

The minister pointed to an example of one report he called “misleading” which included “allegations of harsh treatment of Indigenous people on land rights and cuts to the Aboriginal budget to meet Games funding, the debate about becoming a republic, and claims of hosting a Green Games while polluting the atmosphere”.

Documents confirm all three issues were being debated by cabinet at the time.

Constitutional recognition

During the same period, cabinet opted against public involvement in drafting the proposed preamble to the Constitution, which would be voted on in the 1999 republic referendum.

“This process could potentially prove divisive, highlighting areas of disagreement or promoting expectations for forms of words which are not acceptable to the government,” warned the attorney-general Daryl Williams.

Those concerns centred on whether the preamble should acknowledge the original occupancy and custodianship of Australia by Indigenous Australians.

“A simple recognition of prior occupancy will need to be included in the proposed preamble … we do not envisage the inclusion of a more detailed declaration on Indigenous rights, or reconciliation statement.”

“While the government would retain final say over the wording included in the Referendum Bill, it may be difficult in practice to depart significantly from the model produced through the consultation process.”

Prime Minister John Howard went on to lead the drafting, later removing the term “mateship” following a public backlash.

Australia voted against becoming a republic – and the proposed preamble – in November 1999.

Introduction of the GST

Also revealed in the cabinet papers was Australia’s developing and implementing of its Goods and Services Tax.

“We're probably the first government anywhere in the world which has said ‘vote for us because we want to put a tax on just about everything’,” Mr Costello said of the work done 20 years ago.

It was the tax Australia had to have, he said.

“In my view, it had to be done in Australia and it would always keep popping its head up until it was done - the only way to get rid of this issue, was to do it.”

“I thought they'd be chopping and changing the GST for years but it’s coming up for its 20th anniversary and the base hasn't changed, the rate hasn't changed, the method of collection hasn't changed.”

“Now the only criticism I ever hear of the GST is people who say the rates not high enough.”

Climate change concerns

Another revelation in the cabinet papers was Australia’s generous Kyoto Protocol concessions, which caused diplomatic difficulties the current coalition government is still working to overcome.

The international treaty committed those involved to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“Climate change proved a difficult issue in our bilateral relations with the Pacific Island countries and with members of the European Union.”

“We need to work to strengthen our bilateral ties, particularly with the Pacific Island countries.”

Cabinet was worried about would be best for Australia to ratify the agreement.

“Unexplained delay by Australia could lead to unwelcome domestic and international attention” while “early signature by Australia could be interpreted as confirmation of perceptions that Australia secured an unfairly favourable deal”.

Ultimately, that would happen much later – it was Kevin Rudd’s first act after being sworn in as prime minister in 2007.

“Australia got a good deal at Kyoto,” Mr Costello said. “It is still delivering benefits to Australia 20 years on.”