When Eleanor Gray borrowed a Hello Kitty DVD from her local library in Melbourne at the age of five, a door to a foreign world opened to her.

That was the day she discovered the Japanese series Sailor Moon — via a preview trailer on the DVD — and fell in love with Japanese animation (anime).

She began studying Japanese and cosplaying at anime conventions. Later, after watching an anime series set in a Japanese high school, she went on a university exchange to see the country herself.

Now, the 28-year-old lives and works in Fukuoka, in southern Japan.

"I like to consider myself as an 'ex' otaku now," she tells SBS News.

Otaku is a Japanese term for people who are obsessed with a particular subject — typically computers, video games, anime and Japanese comics (manga).

"After moving and working here full-time, it's definitely less rosy; however, I still frequently find myself admiring the culture and country itself, the more I learn about it and live here."

Japan is one of Australia's key strategic partners and the third most popular overseas travel destination among Australians.

It's developed a multi-billion-dollar content industry, capitalising on the global appeal of homegrown anime, manga and video game products, which have become central to the nation's economic and soft power.

In 2024, one year after overseas earnings from anime production exceeded its domestic revenues for the second time in history, the Japanese government launched its New Cool Japan Strategy, aiming to boost international content-related businesses to $198 billion by 2033.

With Australia launching a review of its National Cultural Policy next year, there have been calls for the government to follow allies such as Japan and South Korea to boost the export of Australian-made content.

While experts say it may not be possible to directly replicate the success of allies in this space, there are some lessons that Australia could consider.

Australia records 'worst' trade deficit in content

Despite a handful of Australian creative exports that have achieved global success over the years — such as kids series Bluey, pop star Kylie Minogue, or actress Margot Robbie — Australia has had "one of the worst creative goods trade deficits in the world", according to Kate Fielding, the CEO of arts and culture think tank A New Approach (ANA).

In a submission to the federal government's 2022 cultural policy review, ANA presented analysis that showed that for every $1 Australia exports in creative goods, $8 is imported from other countries.

Fielding says the National Cultural Policy launched in response in 2023 still had "limited focus on international [exports] within that".

"There are many examples of Australian success in cultural and creative industries, and we should celebrate those, but we should also go as we do with other areas of global export," she says.

"I think that probably Australia has had a long journey to really developing and appreciating our own cultural and creative industries, and ... part of the lag for us as a nation has been maturing and understanding that we have excellent cultural and creative contributions to make to the world.

I think it is time for us to really step forward as a mature nation and take those steps.

But producing creative work overseas can be financially prohibitive for artists.

Under the National Cultural Policy, the government has invested $69.5 million to establish Music Australia and $19.3 million for Writers Australia — both organisations provide direct support for creators to grow international audiences.

A spokesperson for the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Communications and the Arts says artists can also access funding to explore international collaboration and development via Creative Australia and Screen Australia.

Despite these funding avenues, Fielding says Australia's support for arts and culture has been fragmented, and there's a lack of clarity about how Australia's cultural exports are tracking.

"I think probably the first step there would be for the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade to do … a piece of scoping work to see what activities are currently happening, where, within different levels of government and across different agencies," she says.

"That doesn't need to be a comprehensive mapping."

Australia's soft power problem

In a speech on Australia's foreign policy earlier this month, Foreign Minister Penny Wong described Australia as the "architect" of the Asia-Pacific region, citing achievements in securing several geopolitical and diplomatic deals within the region.

But according to the Lowy Institute's 2025 Southeast Asia Index, while Australia ranks second in terms of its influence on defence networks in the region, it ranks ninth in terms of cultural and economic influence.

Australia's creative and cultural exports were identified in a 2017 foreign policy white paper as potential avenues for the nation to exert soft power — which is the ability to attract and influence other countries through non-military measures — along with international education, tourism and migration.

Following the paper's release, the then-Coalition government vowed to develop new approaches to soft power and launched the first-ever Soft Power Review in 2018.

However, the review was discontinued in October 2020, with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade citing impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Melissa Conley Tyler, an honorary fellow at the Asia Institute at the University of Melbourne, says it's time to revisit the 2017 paper, and for Australia to consider other tools of diplomatic influence beyond its security and defence assets, including arts and culture.

"We can do so much in the cultural and creative realm for really very little money compared to the amount of money that, say, defence equipment costs," says Conley Tyler.

A spokesperson for the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade told SBS News the department "works closely with Australia's world-class cultural sector to showcase our creativity, values and diversity internationally".

"Our cultural exports — from film and television to literature, music, design and art — are among the best in the world. They tell the story of who we are and play an important role in strengthening Australia's voice and relationships," the spokesperson said.

What can Australia learn from its Asian allies?

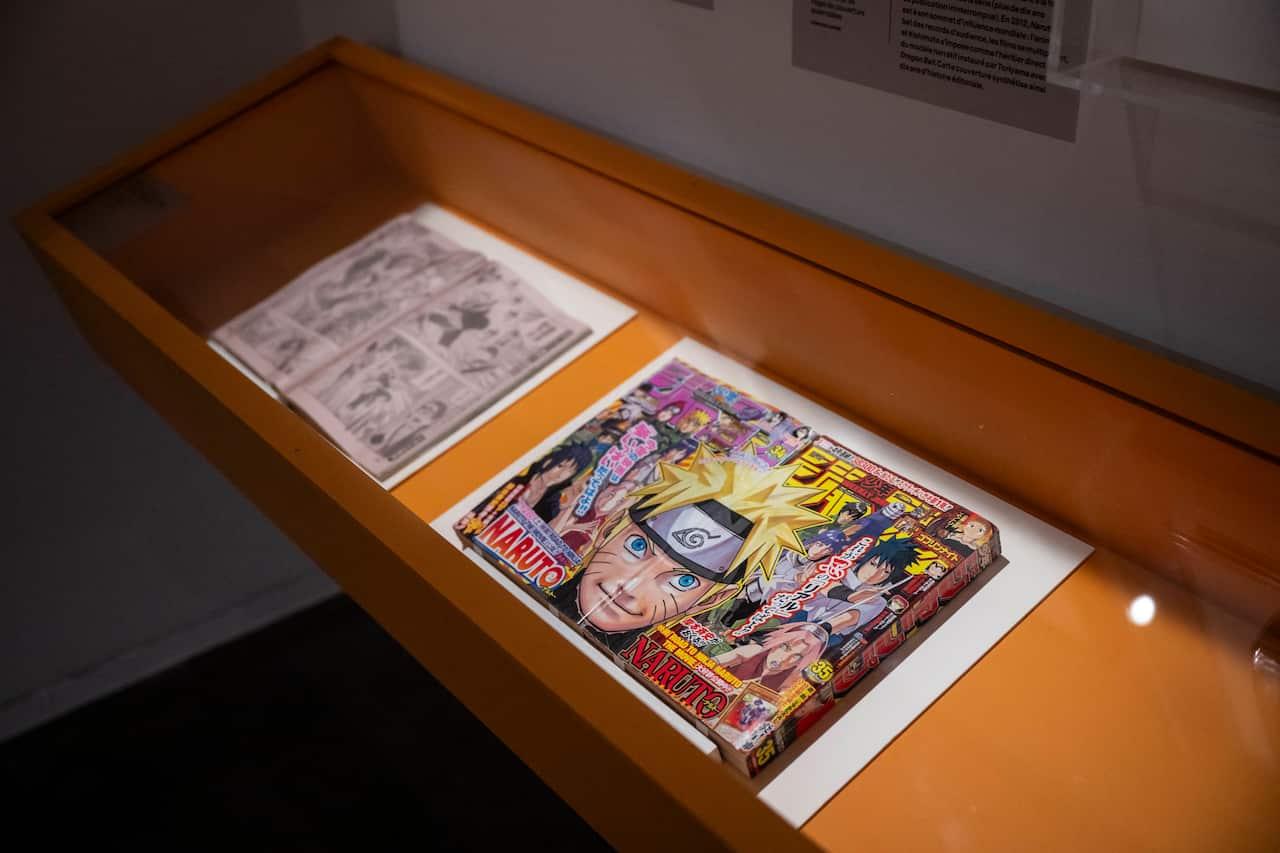

From Japanese manga One Piece to the viral Korean TV series Squid Game, the cultural products of Japan and South Korea have been loved by Australians. While the two countries adopt different strategies to boost their cultural exports, they both enjoy similar levels of government support.

Tets Kimura, an adjunct lecturer in creative arts at Flinders University, says the Japanese government initially had very little to do with the surge of interest in anime, which began attracting international fame in the 1980s.

"[The rise of anime] happened organically, picked up by the Japanese consumers first, then picked up by the foreign consumers," he tells SBS News.

The whole movement happened outside of government control.

As demand for anime grew, so did its profitability.

In 2024, the anime industry contributed a record JPY3.84 trillion ($37.8 billion) to Japan's economy, according to the Association of Japanese Animations. Of that, JPY$2.17 trillion ($21.4 billion) was generated from overseas anime content.

But the anime boom has also come hand in hand with a surge in piracy, which reportedly costs the country billions each year. A 2023 study commissioned by a Tokyo-based anti-piracy group and conducted by accounting firm PwC estimated losses totalling JPY$1.95 trillion ($19.2 billion).

According to Kimura, the growing revenue from international consumers, coupled with the huge economic losses from piracy, has pushed the Japanese government to consider a new economic strategy to maximise profits from the industry.

In 2019, after a decade of various government initiatives, Japan formally launched the first iteration of the Cool Japan strategy, which promotes Japan through multilateral collaboration between the government and private sector in culture, tourism, trade, education and other intellectual property.

"With major changes taking place in the environment surrounding [Cool Japan], the soft power of [Cool Japan] is an extremely potent means of ensuring Japan can maintain its presence and influence on the global stage," the 2019 Cool Japan Strategy paper reads.

'A tool of global influence'

In contrast with Japan, the South Korean government took a more proactive approach to promoting its cultural content in the 1990s, when Korean pop music (K-pop) and South Korean cinema began to grow.

Dr Sung-Ae Lee from Macquarie University recalls a well-cited anecdote during Kim Young-sam's presidency between 1993 and 1998: a government adviser pointed out that the global box-office revenue of Hollywood blockbuster Jurassic Park was roughly equivalent to the foreign sales of 1.5 million Hyundai cars.

Since then, successive South Korean governments — whether conservative or progressive — have launched initiatives to support the creative sector's development.

This includes mandating that state and local governments fund cultural sector initiatives, offering tax incentives and establishing the Korea Creative Content Agency (KOCCA), which oversees global marketing, talent development and cultural export, explains Lee.

Consecutive governments have also sought to reframe political language around the impacts of South Korea's cultural exports, shifting it from the realm of economic policy to "a tool of global influence".

Lee says Australia can learn from South Korea's "coordinated, export-driven cultural strategy", adding that while South Korea has a one-stop agency to manage funding for cultural projects (KOCCA), Australia's support remains fragmented across several organisations.

"Australia could adopt a similar whole-of-government framework linking creative funding with trade, diplomacy and education, turning its artistic strengths into a cohesive and globally recognisable cultural brand," she says.

To amplify soft power, treat artists well first

But simply having a strong cultural sector doesn't necessarily elevate soft power, says Roald Maliangkay, a professor of culture, history and language at the Australian National University's College of Asia and the Pacific.

He says international consumers often view a country's cultural products through the lens of their impression of the nation.

Other nations, including Saudi Arabia and China, have studied the success of South Korea's cultural sector but face challenges in attracting similar international attention, despite their unique cultural products, Maliangkay says.

He says that, although Australia has a rich history of First Nations culture and storytelling, and is viewed positively by the rest of the world, it can struggle selling its content to international audiences due to a lack of a defined modern Australian culture.

"We do not have a more modern culture that people would fondly associate with. [Also,] South Korea and Japan both have a very unique language," he says.

One of the things that people have really enjoyed when they listen to K-pop or watch Korean TV dramas is the idea that by learning a little bit, you gain some cultural capital.

Maliangkay says Australia could look to define its uniqueness by embracing First Nations cultures: "Because that's truly unique, and I think that's an important element."

At the same time, the cultural strategies of both Japan and South Korea have some limitations.

Kimura says the Japanese government offers little support for individual anime creators.

"A lot of those people ... are really, really low paid, and a lot [of them] do not see a promised future unless there's a sacrifice made by the Japanese creators," he says.

In 2024, the Japanese government launched a revised policy, the New Cool Japan Strategy, to adapt to post-COVID digitisation, and acknowledged there's an "insufficient environment for creators to engage in activities".

In South Korea, Lee says gender imbalance in creative leadership, labour exploitation and burnout have been persistent issues affecting the cultural sector.

She also says South Korea's heavy dependence on global streaming platforms has limited its control over revenue and cultural representation —- an issue that Australia's music industry has long identified with platforms like Spotify.

For Australia to boost its cultural exports, not only should it look to proactively address some of these issues, but it has a further hurdle to overcome.

Conley Tyler says to make cultural exports an effective tool of soft power, they need to be "organic".

"They have to organically come from artists themselves, and then be sort of supported and amplified by the government," she says.

"I don't think the Australian government should be deciding what our creative industries are doing, but I think we should understand that they are important and that they deserve to be funded and supported, and that that's in our national interest, just as much as some of the security investments that we make."

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.