At first glance, it might seem like good news. Divorces in Australia have dropped to their lowest rate since no-fault divorce was introduced. And on average, marriages are lasting longer.

Latest data show 2.1 divorces registered for every 1,000 Australians aged 16 and over in 2024.

But while greater longevity of marriages has been heralded as a sign of more successful relationships, the reality is far more nuanced.

Australians are marrying and divorcing less and having fewer children amid increasing economic insecurity. It's emblematic of deep and complex social change.

Fifty years of divorce without fault

Divorce in Australia has changed significantly since the 1975 reform that removed the requirements to show fault. That is, couples could now go their separate ways without having to explain themselves.

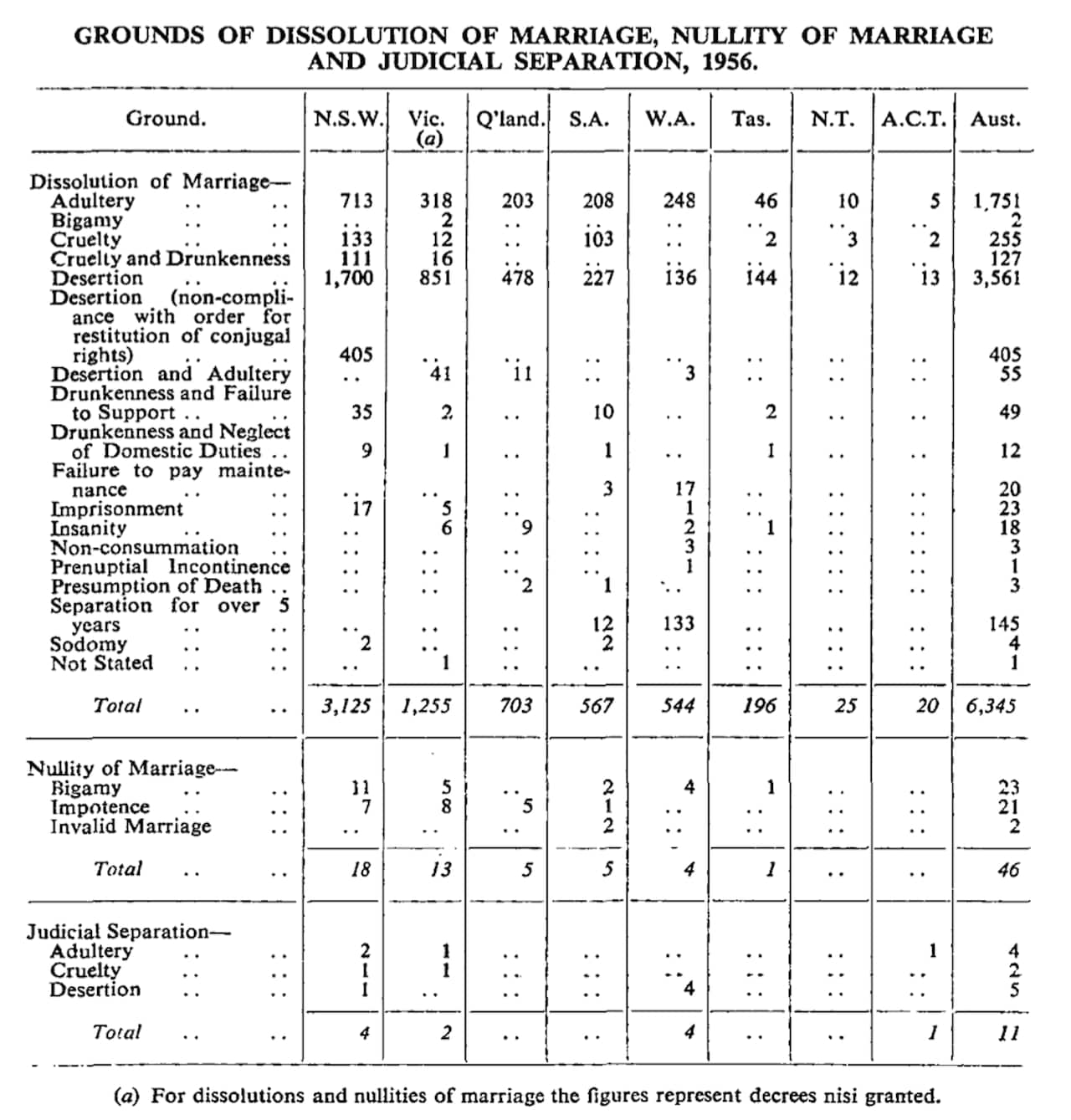

For 20 years before no-fault divorce, marriage dissolution was reported by court-decreed fault and included among official crime statistics.

Included among the more than a dozen grounds for divorce were adultery, drunkenness and non-consummation.

When Australians divorce now, they're older — 47 years for men and 44 for women — reflecting increasing age when marrying and longer duration in marriage.

Marriages are typically lasting just over eight months more to separation and nearly 11 months longer to divorce than in 2019, the year before the COVID-19 pandemic started. Such an increase points to a swift and sharp change likely brought on during and since the pandemic.

But this doesn't mean we're getting better at navigating relationships — rather, Australians are remaining longer in marriages due to economics.

Cohabiting before marriage is also increasingly common, enabling relationship testing.

Most Australians believe marriage isn't necessarily a lifelong thing, reflecting widespread acceptance of divorce. But marriage remains an important aspect of our lives.

Fewer brides and grooms

Marriage remains a major part of Australian society, with most Australians marrying at some point in their lives.

Marriage equality, enshrined in law in 2017, reflects the enduring relevance of formal marriage.

But there have been some changes.

Religion no longer dominates marriage, with most weddings officiated by celebrants. This trend has continued since the late 1990s. In 2023, more than 83 per cent of marriages were conducted by civil celebrants, not a religious minister.

Latest figures show marriages have steadied since the COVID-19 slump and rebound, with Australians marrying less on average now than before the pandemic.

Overall, the rate of marriage has more than halved since 1971, dropping from 13 marriages per 1,000 people aged 16 years and over to 5.5 in 2024.

Marriage rates are now well down from the peak set during Australia's post-war baby boom, where increased and younger coupling drove record birth rates in the 1960s.

While most children are born to married parents, the proportion has changed substantially over the years. In 1971, 91 per cent of births were to married parents, declining to 60 per cent in 2023.

The paradox of choice

Choice is generally increasing when it comes to relationships, but also becoming more constrained on the family front.

The choice not to be in a relationship is increasing. Whereas in the face of socioeconomic challenges, choices around building a family are more limited.

Many Australians now won't achieve their desired family size because the barriers to having a much-wanted child, or a subsequent child, are insurmountable. Financial and social costs of raising a child while juggling housing affordability, economic insecurity, gender inequality and climate change are just too high.

The proportion of women without children over their lifetime nearly doubled from 8.5 per cent in 1981 to 16.4 per cent in 2021. On average, Australians are having fewer children than ever, with the total fertility rate at a record low of 1.5 births per woman.

Changing expectations and norms concerning coupling and childbearing have enabled greater empowerment for Australians to choose whether they marry at all. Women especially benefit from more progressive attitudes towards remaining single and childfree.

The costs of divorce

Costs associated with a divorce can be high, with a "cheap" marriage dissolution starting upwards of $10,000.

Couples have become creative in navigating marriage breakups during a cost of living crisis.

Where children are present — 47 per cent of divorced couple families — parents are looking for new ways to minimise adverse social and economic consequences. "Birdnesting", where kids remain in the family home as parents rotate in and out according to care arrangements, is one such solution.

Novel child-centred approaches to family separation are most successful where relationship breakups are amicable. Around 70 per cent of separations and divorces involving children are negotiated among parents themselves.

Ever-increasing numbers of Australians are living apart together (known as LATs), where they are a couple but live separately. This is particularly common among parents raising children. It's a novel solution for parents who don't want the headache of having a new partner move in with them post-divorce.

Rising housing costs and widening economic insecurity mean separation may not even be an option, especially where children are involved. Research shows soaring house prices can keep people in marriages they might otherwise leave.

Living under the same roof and raising children while separated is increasingly a response to financial pressures. Where relationships involve financial dependence and high conflict, such arrangements are forcing families into potentially highly volatile circumstances.

Families are changing and diversifying, and policy must reflect this.

Cost of living pressures are increasingly denying couples much-wanted families and making it more difficult for families to thrive, divorced or not.

Liz Allen is a demographer at the POLIS Centre for Social Policy Research.

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.