In 2022, Deniz Toupchi sat outside Australia's federal parliament and didn't eat for days, calling on the government to act against the Iranian regime. But those cries went unanswered for nearly three years.

At the heart of her protest were two main demands: expel Iran's ambassador and designate the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) — a key branch of Iran's military — a terrorist organisation. (The IRGC plays a pivotal role in the country's domestic and international policies.)

The three-day hunger strike of four Iranian-Australians, including Toupchi, happened just after the suspicious death in custody of an Iranian woman, Mahsa Jina Amini, for allegedly not observing the country's mandatory hijab laws, which sparked the 'Woman, Life, Freedom' uprising in Iran.

"We saw what the regime does to our people in Iran and how they open fire on their people. So it was a kind of warning sign for us," Toupchi tells SBS News.

"We thought we were living in a democratic country with those regime-related people, such as the ambassador.

"That's the main reason we did that hunger strike."

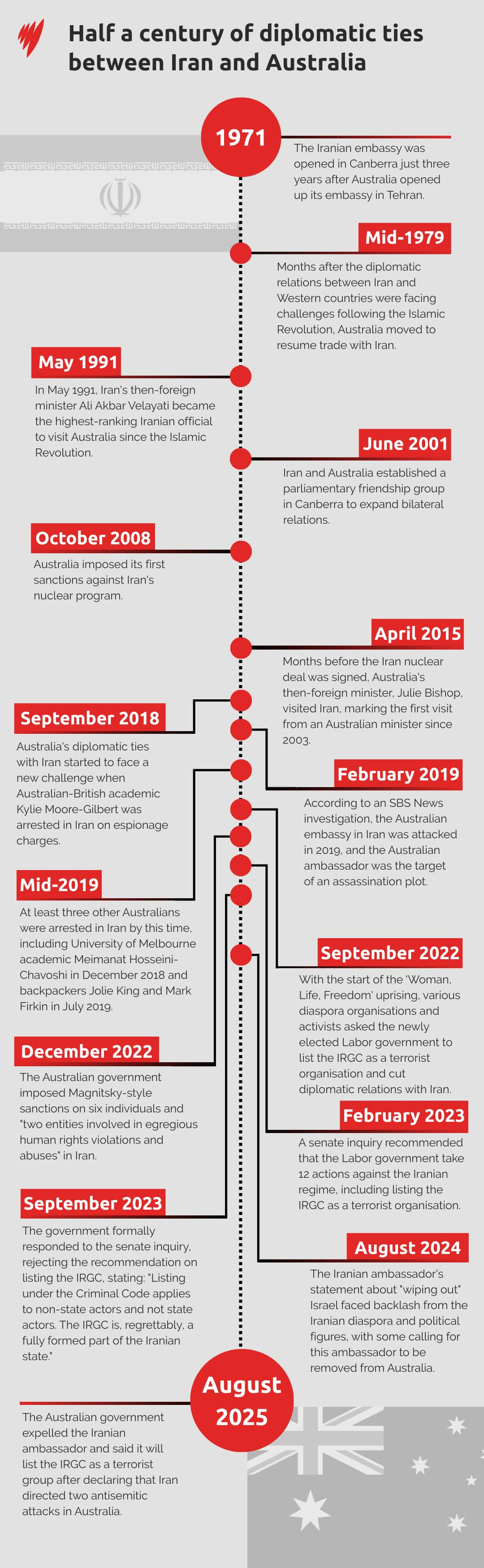

Almost three years after the strike, on Tuesday, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese announced the government had expelled the ambassador and would list the IRGC as a terror organisation after declaring that Iran directed two antisemitic attacks in Australia.

Several community organisations and members, such as Toupchi, have supported the decision.

"We protested, we went on hunger strike outside the parliament, and we raised our voices again and again through the 'Zen, Zendegi, Azadi' [Woman, Life, Freedom] movement," she says.

"When we did that [strike], and didn't see any real actions from the government back in those days. I felt ignored.

But now these days, I feel real relief and validation.

The recent actions by the government against the Iranian regime align with the demands of campaigns led by members of the Iranian diaspora since 2022.

Though dissidents like Toupchi believe it came too late.

"I was just a little bit annoyed because we've been asking for these actions since 2022. If our voices had been heard back in 2022, I believe those horrific attacks wouldn't have happened at all."

'Iran is not a friend'

The calls for action against the Iranian regime by Australia were mainly first raised between late 2018 and mid-2019, when at least four Australians were arrested in Iran.

Kylie Moore-Gilbert, a research fellow at Macquarie University, who was jailed for two years in Iran on espionage charges, was among them.

While Moore-Gilbert doesn't think "the Iranian diaspora was ignored" by the government, she says politics is "unfair" sometimes.

"I also feel like I wasn't listened to, particularly when it came to sanctions," she tells SBS News.

"I'm not the only Australian citizen who's been targeted by the IRGC, and you know, they wouldn't even sanction the judge who sentenced me to prison, or any other official whose name I provided linked to the IRGC either."

Some experts have described Moore-Gilbert's detention as an example of hostage diplomacy by the Iranian regime, arresting foreigners as bargaining chips to use in prisoner exchanges.

Moore-Gilbert says at first, after her release, her arrest "didn't seem to affect the [Iran-Australia] relationship that much".

"But I do think that behind the scenes, it must have soured some aspects of the relationship," she says.

"I hope that it did contribute to a greater understanding among the diplomatic class that Iran is not a friend, and then they need to take the threat of Iran more seriously."

'It was the voice of the community'

Almost two years after Moore-Gilbert's release, in 2022, Mahsa Amini's death sparked deadly protests across Iran, and this led to Iranian Australians protesting in support of dissidents in Iran and asking their governments to take more action against the regime.

Community organisations such as Australian United Solidarity for Iran (AUSIRAN), a community-led group, were established at that time to lobby on community demands.

"From the beginning of our activism, these demands, the expulsion of the ambassador and listing IRGC as a terrorist organisation, were on top of the list, not only for our organisation, but it was the voice of the community," AUSIRAN spokesperson Rana Dadpour tells SBS News.

"There were several other groups and many community members and individuals who raised their voices for this."

A 2023 Senate inquiry recommended 12 actions against the Iranian regime, including listing the IRGC, but the government said it couldn't list a 'nation-state' group.

Liberal senator Claire Chandler, who chaired the inquiry, says one of the reasons it called for the listing was "because the Iranian diaspora were absolutely passionate and uniform in advocating for that".

"We heard it loud and clear from the diaspora throughout the inquiry, and that's another one of the reasons that we made it very clear that we think it needed to be listed."

In May 2025, following an SBS News investigation into an alleged assassination attempt on a former Australian ambassador to Iran, Ian Biggs, the demands made to the Senate inquiry were echoed by diaspora members and organisations.

At that time, Foreign Minister Penny Wong defended the government's position on Iran when SBS News asked why Biggs was allegedly targeted, saying the government "has taken stronger action in relation to Iran than any previous Australian government" and pointing to to sanctions and human rights declarations the government has previously made.

Why Australia held onto diplomatic ties with Iran

Now, five months after these remarks, the government has announced its decision to list the IRGC as a terrorist organisation and expel the ambassador, Ahmad Sadeghi. Sadeghi left Australia on Thursday night.

Moore-Gilbert says it may have been delayed because "Australia does have some interests in Iran".

"[I] believe that wings of the government arms and agencies of the government were against the idea because they had other interests in Iran they wanted to maintain, including the diplomatic relationship," she says.

"Whereas parts of the government that were interested in national security and were more interested in safeguarding Australians here at home than they were in the diplomatic relationship, were perhaps more inclined to list [the IRGC].

I think it became an internal issue within the government, which factions were in favour and which were against, and who would win out in the end.

Albanese said the decision came after intelligence agencies linked the IRGC to antisemitic attacks on a Melbourne synagogue and a Sydney restaurant.

A Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) spokesperson told SBS News that "expelling an accredited ambassador and announcement of intention to list the IRGC as a terrorist organisation are unprecedented actions".

Dara Conduit, a lecturer in political science at the University of Melbourne, says: "The fact that it has been proven — there is obviously evidence … that directly links the IRGC to the attacks — means that the Australian government had enough evidence to take this step."

Conduit says the Iranian diaspora in Australia has also "played a really important role in keeping the question of proscribing the IRGC central".

"It's something that the government has been asked about over and over again in recent years, and I think a lot of that is because of the way that the Iranian diaspora has made sure that it remains part of the political agenda."

'Horror situation' for those in Iran

On Tuesday, ASIO director-general Mike Burgess said the organisation had uncovered links between the alleged crimes and commanders in the IRGC, and there was "a layer cake of cut-outs", or intermediaries, between the IRGC and the alleged perpetrators conducting crimes.

Moore-Gilbert says listing the IRGC as a terror group means that ASIO can implement "law enforcement tools that they didn't have before to crack down on anyone inside of Australia who's acting on behalf of the IRGC".

"They have far more powers now to go after anyone who's acting on behalf of the IRGC inside Australia and to arrest them and charge them with supporting a terror organisation," she says.

However, with Australia-Iran relations reaching a breaking point, there are concerns for Australian citizens inside Iran – especially for those who may be detained in Iran.

In October 2024, an SBS News investigation revealed that at least two Australian citizens are imprisoned in Iran.

DFAT's spokesperson told SBS News this week: "The Australian Government remains committed to supporting Australians in Iran in need of consular assistance, even where our assistance may be limited.

"Our ability to provide consular assistance in Iran is extremely limited, both for Australians and dual Australian-Iranian nationals. This advice has been reflected in the government's 'Do Not Travel' advisory for Iran for a number of years.

"We continue to advise Australians 'do not travel to Iran'. If Australians are in Iran, they should strongly consider leaving as soon as possible, if it is safe to do so."

Moore-Gilbert says she is "very worried" about the fate of those who may be facing the same situation she did in Iran.

"If diplomatic relations have really degraded, it's a horror situation."

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.