On paper, Billy and his wife seem like the kind of couple who could afford to buy a house in Sydney: They earn a combined household income of $350,000 and own two apartments.

The North Shore residents are expecting a child and have been looking to buy a four-bedroom family house for up to $2 million, which is the upper range of what they can afford.

But after months of house-hunting, they are starting to lose hope.

"We were initially amazed that we could borrow this much and we thought we'd get something for it — but now we've started looking and it's kind of like 'what the?'" Billy says.

It just feels like the goalposts keep moving.

Data shows Australians are finding it increasingly difficult to upgrade from starter units to family-sized houses, meaning their first step on the property ladder may actually be their final one.

It coincides with a drop in the proportion of three-bedroom properties available, which experts believe needs to be addressed.

KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley says data shows that since the COVID-19 pandemic, it's become harder to upgrade from an apartment to a house.

Price gap is bigger

In 2019, the price gap between a median unit or townhouse and a median house was 28.3 per cent, but this climbed to 72.3 per cent in the latest figures for 2024/25, according to Rawnsley's analysis.

Those who owned a median unit or townhouse in 2019 could have sold it for $700,000 and purchased a median house for around $900,000, which is not a massive gap, he says.

The median unit or townhouse is now worth about $800,000, while the median house costs around $1.4 million, which is a much bigger jump.

This is because house prices have grown much faster than unit prices.

In Sydney, the median house price is now $1.7 million, according to Domain.

Henny Rahardja, principal buyer's agent at OH Property Group, says she has noticed buyers in Sydney are finding it difficult to upgrade.

"Buyers can't easily make the jump from $1.2 million apartments to $2.8 million houses, for example," she says.

This may be even more challenging in suburbs where land sizes are larger.

"Buyers may be okay to buy a house on 500 square metres of land, for example, but this is not helpful if the average land size in the suburb is 900 sq m.

"I think there is a lack of diversity in housing options available at the various price points."

'Hoping for a Christmas miracle'

Billy, 37, and his wife believe they've likely reached the peak of their earning potential and say it's been disappointing to see what they can actually afford to buy in the North Shore, where they would like to stay because it's close to their family.

We're getting priced out very easily, especially for things that fit our criteria, which is something that's livable [and] in a decent location.

Properties they've found for around $1.8 million are either dilapidated, on busy roads or don't have much growth potential.

"The odds are against us," Billy acknowledges, saying they will keep trying but might have to compromise on liveability.

"We may have to live in something a bit more cramped and maybe save and try and do renovations in the future."

Billy owns a two-bedroom unit in Baulkham Hills, and he and his wife currently live in a three-bedroom unit that she bought one and a half years ago.

His wife's parents helped her to buy the property and Billy says the pair don't feel like it's an option to ask their families for more assistance.

Out of a matter of pride and self-respect, I guess, because we know we've already gotten help, it doesn't feel right to ask or continually ask for more help until we've given back a little bit.

Even if they sold their properties, they would not have enough funds to substantially boost their borrowing capacity, as they also have to cover capital gains tax.

If they can't find something appropriate, they will probably stay where they are, and Billy says they may have to rethink their careers and pivot in order to gain more income.

"[But] I think that's difficult. The market's moving faster than our salaries are," he says.

"We're hoping for a Christmas miracle.

"If there's any time for a miracle to happen, it's normally around Christmas time because people go away on holiday [and] there's not a lot of interest then."

Supply of three-bedroom properties is falling

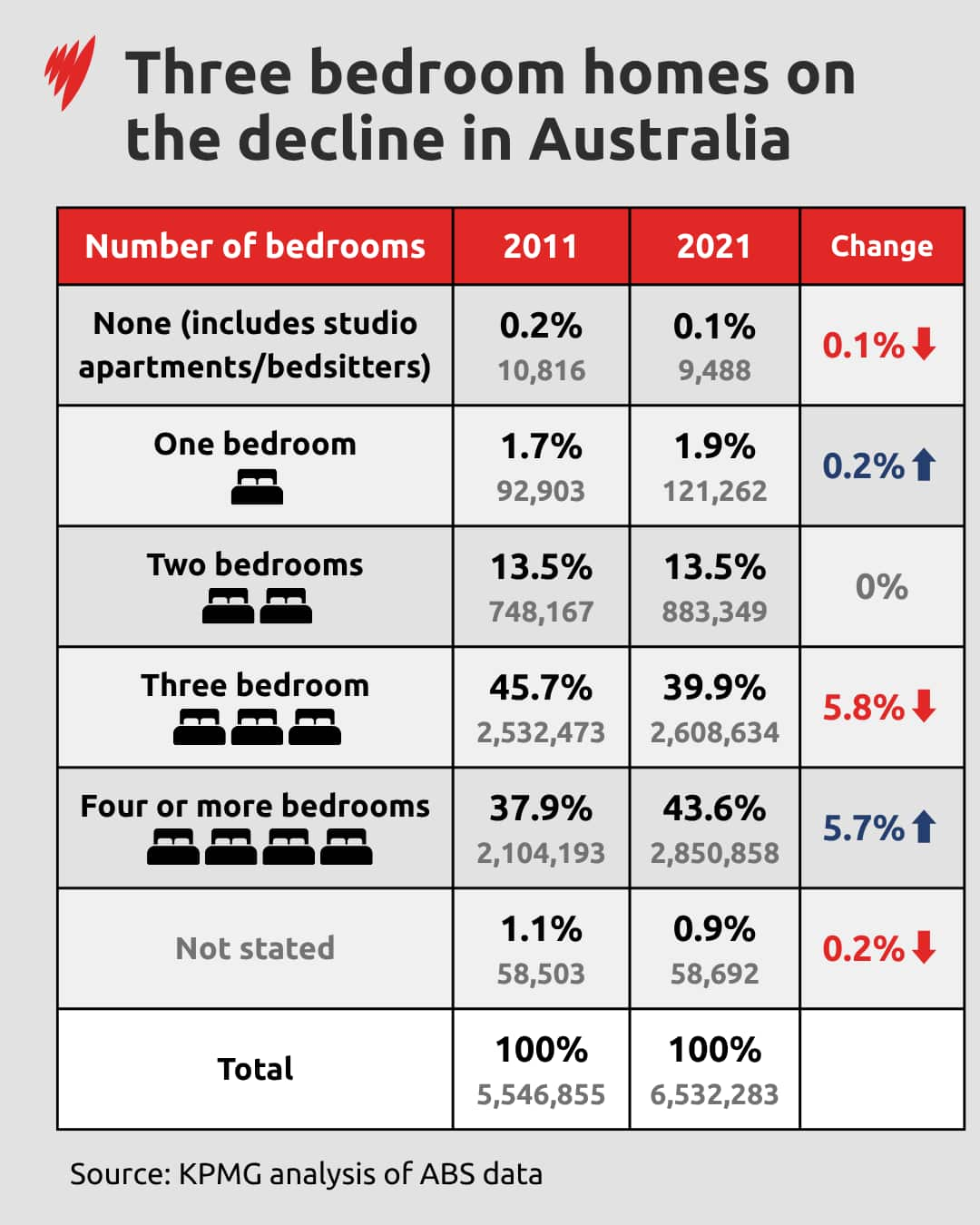

Part of the problem is that the proportion of three-bedroom properties in Australia has dropped in the past decade.

These properties appeal to both families and downsizers but they are becoming harder to find.

Rawnsley says three-bedroom properties made up almost half of those available in 2011 (45.7 per cent). But this had dropped to 39.9 per cent by 2021.

The proportion of one- and two-bedroom properties stayed roughly the same, while the proportion of properties with four or more bedrooms rose from 37.9 per cent to 43.6 per cent.

There are now more properties with four or more bedrooms (2.8 million homes) than with three bedrooms (2.6 million homes).

The emphasis on building higher-density apartment blocks with one or two-bedroom dwellings, as well as larger homes on the urban fringe, appears to be depleting the proportion of three-bedroom properties available.

Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute managing director Michael Fotheringham points out that Australia builds many more houses than apartments, and these are mostly concentrated on the urban fringes.

For each individual apartment, we build six houses and that continues.

"Seventy per cent of our housing stock is houses rather than apartments or townhouses. About 15 per cent is apartments and about 15 per cent is townhouses."

But the recent focus on building apartments could also be contributing to the scarcity of three-bedroom properties as family-friendly houses in desirable areas are knocked down to make way for apartments, and developers generally prefer to build one- or two-bedroom units.

Any three-bedroom units included are often designed as luxury penthouses, making them unaffordable, or are designed to be rented, so they often don't have large living areas suitable for families.

The median price for a three-bedroom unit in Sydney is also higher than for a three-bedroom house, partly because units are often more centrally located.

Developers shifting focus

Florian Caillon, head of acquisitions at property developer Third.i Group, says three-bedroom dwellings are generally more expensive and can take longer to sell, so some developers may not want stock sitting there for extended periods as they've got interest and other costs to consider.

But he says the group's research has found a spike in people saying they are interested in three-bedroom units in Sydney suburbs such as Gladesville and Crows Nest, and even Newcastle in NSW.

We've definitely seen that on the ground, that people are wanting larger units now because they're being priced out of the traditional home market.

In response, Third.i is changing its focus and the first stage of its new development in Crows Nest will have a greater emphasis on three-bedroom units.

James Alexander-Hatziplis, the chief executive officer of Sydney architecture firm Place Studio, says he has noticed a real shift in the market.

"Developers are starting to focus on apartments that work for a wider mix of people, not just first-home buyers or downsizers," he says.

"When you build slightly larger, more flexible apartments, especially with an extra bedroom, they simply last longer in terms of how people can use them.

"This is, at its core, a more sustainable outcome as it reduces the need to replace redundant housing that doesn't meet society's needs."

Push for more family-sized homes

Professor of planning at Western Sydney University, Nicky Morrison, says previous policy settings haven't clearly signalled that three-bedroom homes are a priority and the market alone has not delivered family-sized apartments at scale.

"At present, we don't build enough well-located, family-sized homes," she says.

She stresses that governments should be encouraging developers to build more three-bedroom apartments because they give families and downsizers the ability to stay close to jobs, schools and transport, rather than pushing them to the fringe.

Both the Victorian and NSW governments have recently introduced new planning incentives to encourage more family-friendly housing.

Victoria's townhouse and low-rise code enables homes of up to three storeys to be fast-tracked through the planning system. One in 10 homes will be required to have three or more bedrooms.

"The only way to make housing fairer for young Victorians is to build more homes faster — that's why we're delivering the biggest overhaul of Victoria's planning laws in decades, bringing Victoria's old-fashioned 'NIMBY' planning laws into the modern era," a Victorian government spokesperson says.

According to a spokesperson for the NSW Department of Planning, Housing and Infrastructure, the state government is focused on increasing housing diversity through reforms such as the NSW Housing Pattern Book and its low and mid-rise housing policy.

"This will encourage development of a wider variety of homes suitable for families, including three-bedroom homes," the spokesperson says.

The pattern book provides high-quality home designs for low and mid-rise housing that can be fast-tracked through planning processes. It includes terraces, row homes and mid-rise apartments.

But the spokesperson says councils are primarily responsible for establishing dwelling mix controls, including requirements for more three-bedroom homes, through their local environmental plans or development control plans.

While Morrison agrees, she says state-level policy signals strongly shape what councils can mandate.

"That is why clearer guidance, incentives and design standards at the state level still matter."

Relief could still be a few years away

Rawnsley says the impact of off-the-shelf plans for townhouses or medium-density development will take a few years to realise.

"We'll hopefully start seeing more of this missing middle townhouse coming into fruition over the next couple of years," he says.

"We've got lots of developers who build lots of Greenfield housing on the fringe, but we don't really have a very deep or established market of developers who really specialise in this townhouse market in large numbers."

It's hoped the supply of townhouses, terraces and other mid-rise apartments will provide another rung on the property ladder that’s more affordable than a standalone house.

When asked whether he believes the concept of a property ladder still works, Rawnsley says the first step is getting much harder for first-home buyers to climb.

"But we know that apartments are more affordable, so apartments are still the first rung," he says.

"The next step up is going to be a more challenging one [than previously expected] — you have to build more equity, save more money to get to the house.

"Or you remain in that apartment for the long term. It becomes the final step on the property ladder, rather than the [first] one.

"There's always been compromise in the property ladder but now some of the compromises between budget, locale and size are really not practical for people to make."