INTERACTIVE FEATURE: A story of survival - 70 years on from Hiroshima

I was a pretty normal kid growing up in the late '80s. I wore pumps, I had a hyper-coloured t-shirt collection, I rode my BMX bike around the neighbourhood with my mates. The biggest issues in my life included obtaining a Michael Jordan basketball card and scoring for my soccer team. My point here: I was sheltered from the real problems of the world - as many Australian kids tended to be (if not, also many Australian adults).

But that changed one primary school day. I wouldn’t realise it - or be thankful for it - for many years to come, but it was a chance encounter with a children’s book that offered my young self a brief glimpse behind the veil of the simple world I knew. The book was titled My Hiroshima, written by Junko Morimoto. Junko has become a prominent Hibakusha in Australia, where she resettled after the Second World War. 'Hibakusha' is the term used for surviving victims of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear bombings - twin horrors we can scarcely imagine today.

Junko was just a schoolgirl the August day in 1945 when the Enola Gay bomber dropped the bomb they had named ‘Little Boy’ on her hometown. By some estimates, it claimed around 80,000 lives, instantly - but figures vary. Junko had been sick that day and had stayed home from school. She would be the only one of her 360 schoolmates to survive the bombing. Junko’s children’s book does more then tell of that day - it shows us, through simple and elegant illustrations that stayed with me for decades after that first primary school reading. Sitting cross-legged on the floor as our teacher read Junko’s book to us, I remember being touched by this innocent girl’s story. It was the first time I had really understood that truly horrific things can happen in the world.

I must have only been seven or eight years of age at the time, but that first reading of My Hiroshima imbued me with a sensibility I believe has stayed with me in many ways. I vividly remember a classmate had giggled when our teacher read about Junko's sister, who had ended with a hole through her lip following the nuclear blast because she was eating with chopsticks at the time. I remember shooting him a look and telling him to shush. This was serious. I knew this was serious. This book reached through to me, as I believe it has reached countless other Australian school children in a similar way, from that day to this.

Although the core lessons from Junko’s tale lingered ghostly in my subconscious, I eventually forgot about this chance encounter with My Hiroshima. That was until some 25 years later, when I was sent out to interview a Hibakusha living in Sydney’s northern suburbs. It had been so many years since that primary school reading and the name Junko Morimoto had washed from my mind.

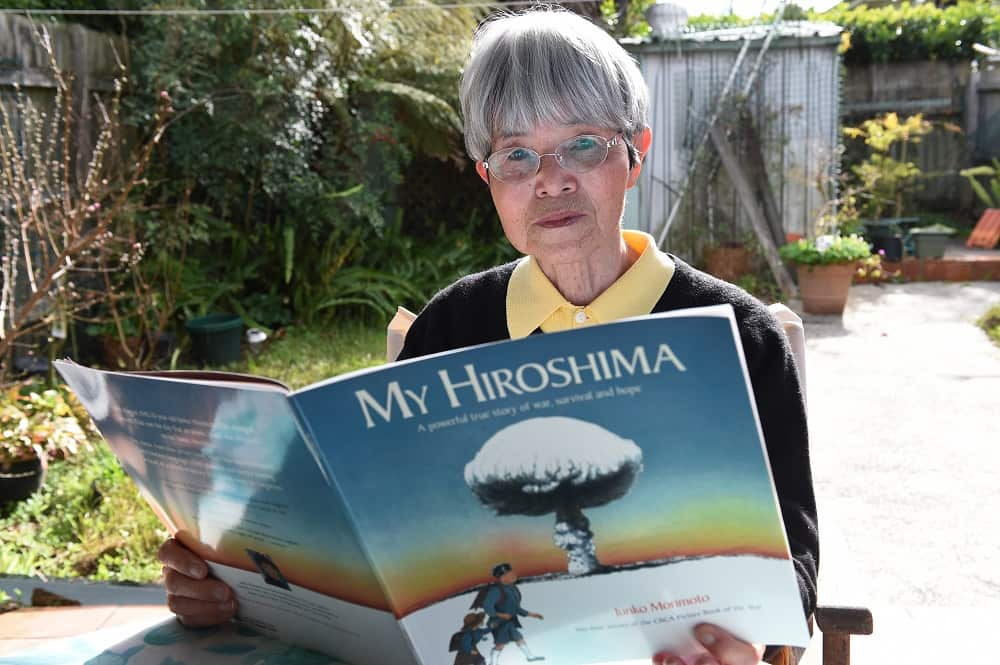

I stepped into the backyard of a small house owned by a diminutive and frail elderly lady who introduced herself in Japanese as Junko. We sat and she began telling her story of survival in the hours, days and weeks after the bombing of Hiroshima. It was emotional and engrossing. Junko spoke simply, but with the quiet power of a person who has seen the worst of what the world can conjure. I knew she had written about her experiences, but it wasn’t until she handed me a copy of her book, My Hiroshima, that I realised who I was talking to.

There was no mistaking the cover page illustration showing two Japanese school children with a giant, white mushroom cloud in the background. It was an emotional homecoming, of sorts - Junko, the moral tutor I’d never met. Junko’s art and storytelling had influenced my development as a child in a way a few other things could have. And I had only realised it sitting across from her more than two decades later.

Being exposed to Mr Hiroshima as a child did not turn me into a fervent anti-nuclear activist as an adult. But it did mean I would grow up with the firm understanding that nuclear technology, peaceful or not, must be treated with respect, if not trepidation.

Today marks the 70th Anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, and it comes at a poignant time. Japan is still dealing with the fallout from the Fukushima nuclear disaster; world powers have just agreed to a deal with Iran to curb the Islamic Republic’s nuclear ambitions; South Australia has announced a royal commission into nuclear issues and is considering a nuclear waste facility somewhere in the state; Australia now makes billions of dollars from uranium exports; and, climate change is convincing many we should turn away from fossil fuels and towards alternative sources of energy, nuclear among them.

The atomic lobbyists argue nuclear is our future. The anti-nuclear lobby argues the trap-door is swinging beneath us. Either way, we have much to learn from the nuclear tragedies of our past. Let’s hope some of those walking the corridors of power had a chance encounter as a child with a simple book about a Japanese schoolgirl and the day an atomic bomb destroyed her world.