It’s a childhood spent without social media, coveting shampoo and spray-on deodorant. How do kids growing up in juvenile detention see the world – and their futures?

He is a neat boy, sometimes broody. Like many 15-year-olds, he is not a big talker. He loves cars and football and wants to become a professional player. But his dream rests in his imagination, for now, because he has been temporarily removed from society.

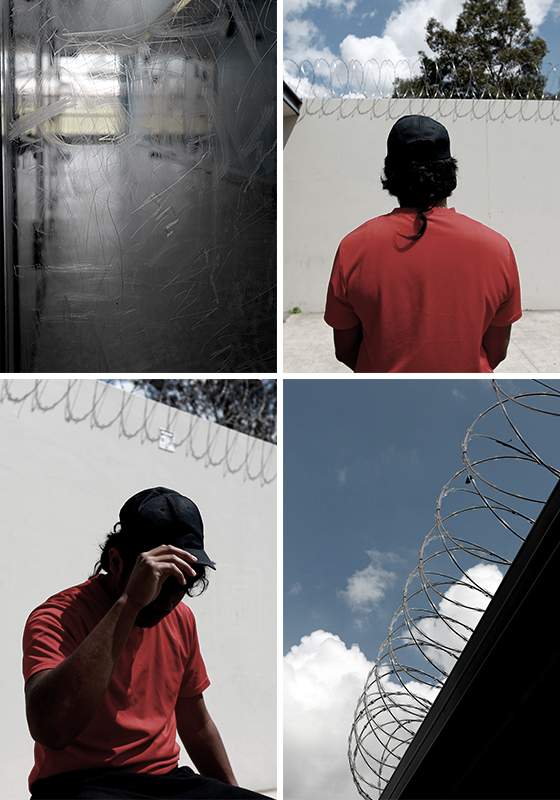

For most of this year he has lived at the Reiby Juvenile Justice Centre on Sydney’s fringe. Bound by things he has habitually resisted, his days are a carefully orchestrated regime of school, routines and rules. His nights are passed in a small cell where his few possessions are proudly displayed.

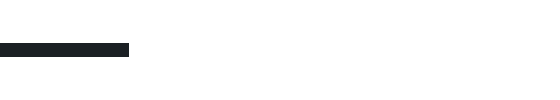

Six packets of cards, a small hairbrush, a roll-on deodorant, a tube of moisturiser and a bottle of shampoo are spaced perfectly and aligned in ascending order on the sill of his barred window. Two sun hats, rewards for good behaviour, have been placed carefully on the adjoining bench, which, like almost everything in his room is fixed and hard. A television, protected by a metal and Perspex box, takes up the other end.

His sparse wardrobe (undies and a couple of t-shirts) is folded neatly on the upper part of a small alcove. Puzzles and water bottles take up a lower shelf.

Apart from his tableau of prized toiletries, the only other personal touch is the collection of sporting posters he has carefully stuck to the back of his cell door. Anything he arrived with is in storage for the term of his sentence. Everything else could fit into a shopping bag.

He first came to Reiby almost five years ago. Not quite 11, he was scared and nervous, far from home. But that first stint in a children’s jail did not deter him from spending even more time here, even though he had few visitors and never stopped missing his family. And so the latter end of his childhood morphed into an endless loop: offending, incarceration and release.

“I’ve been in and out, so it feels like home,” he says of the decades-old centre, with its razor wire-topped walls. He speaks quietly, perching on the carefully made bed that takes up most of his room.

“I know nearly every single worker here. They treat me with respect. I treat them with respect.”

Like the rules that govern almost every aspect of life at Reiby (no phones or keys for visitors; no plastic spoons to be removed from the café) there are rules for writing about him. He cannot be identified, nor asked about the crime that brought him here. But what he lacks in authorised detail is counterbalanced by statistics. Last night he was one of 45 boys at Reiby and one of 929, on average, who spent the night in custody somewhere in Australia.

Contact means 10-minute phone calls and two visiting days, which are often poorly-attended.

Just over 300 of them were in NSW, at one of seven centres: a few outside Sydney for older boys, and one just for girls. Whether on remand or accused of murder, every boy aged 10 to 16 was kept at Reiby, a decades-old facility notable not just for its wired perimeter, but also for its abundance of adults.

Occupying a large block in outer-suburban Airds, Reiby is surrounded by other children. A primary school, with its motto “courage and determination”, backs on to the centre. Across the street is the local high school, where a class of teenagers tosses a ball in the open on a sunny school day.

They are only metres away, but the boys of Reiby hear and see none of this. Behind heavy walls and rows of locked doors, their lives are regimented and reclusive, as they spend their days separated into one of four units, each containing up to15 youths. The small groups rarely meet.

Up to 55 boys can stay here at once. Like other teenagers, they attend school, have a weekly homework club and learn the vocational skills of sign writers and baristas.

Sometimes football players visit. And in summer, the boys can swim in the ageing pool, but they do so within the constant confines of a segregated centre, with its central grassed area surrounded by blocks of locked rooms. Even the outdoor furniture is moulded and immovable.

For these children, contact with the wider community is restricted to seven 10-minute phone calls every week, plus two visiting days, which are often poorly attended. They have limited access to the online world that dominates the lives of the rest of their generation, but they do have occasional sessions for coping with grief. Wherever they go, they are shadowed by adults, all hooked up to radios and ever-vigilant for the threat of violence.

“This place is like an assessment tool,” says Lee Bromley, who ministers to an endless stream of children as Reiby’s chaplain. “If there’s a family struggling in NSW, we see it here.”

An overwhelming number of boys who spend time here – overnight on remand, or serving a sentence of months or years – come from disadvantaged backgrounds. Their crimes often occur during a period of crisis.

Yet despite all the losses that life at Reiby entails – of liberty, access to social media, and the simple joy of walking to the park to kick a footy – this place will become increasingly familiar to many. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, every second 10 to 16-year-old released from detention in Australia will be in trouble again within six months. And 76 per cent will have their freedom curtailed again within a year.

"If one kid breaks the cycle, he could be saving that whole generation."

“The one thing you are always mindful of is that if these kids don’t break the cycle, their children are going to go through that same thing as well,” says programs co-ordinator Sam Lene, who initially resisted the chance to work at Reiby two decades ago.

“I just couldn’t get my head around working in a prison. Probably that stigma of trying to work with difficult people.”

Programs co-ordinator Sam Lene

But the past eight years have proved to be surprisingly gratifying, if sobering.

“I am conscious of the reasons why they are here, and it’s probably better for them to be in here,” says Lene, a warm and supportive man, as a couple of youths are walked across the central grassed courtyard. He pauses briefly to banter with them.

“If one kid breaks that cycle, then he could be saving that whole generation.”

For some, that cycle is one of offending and re-offending. For others, it is inter- and even intra-generational. It is not uncommon for cousins and sometimes siblings to be here at the same time.

“I think I’m not coming back, but it’s just peer pressure,” says the second boy, who is perched on an outdoor table, an adult supervisor in civilian clothes hovering metres away.

The boy is 15, but looks older. His voice is flat, his shoulders hunched. Even though he reflexively shakes hands, like every other boy we meet, there is a wariness and weariness about him.

What’s it like to be here?

“Real shit,” he says, and looks down at his unit’s courtyard, with its stark mix of pebbled flooring and brick walls. “It’s not a good place to go, because you’ll end up thinking about family.”

His is nowhere close. He rarely sees anyone who does not live or work here.

“You’ll miss home,” he says quietly. “No matter where you go, you’re always thinking about it.”

He, too, has been here before. When he was released, no-one enrolled him at school again, so he never returned. Back at Reiby, he has no choice but to attend class every day.

“It’s like a Christian school, no swearing and that,” he says, almost reverently, of the in-house Dorchester Education and Training Unit, where he spends his weekdays following the NSW curriculum from behind locked doors.

The average boy at Reiby will not have not been to school for the last two years.

“So their last memory of school for a lot of them is primary school,” says principal Robert Patruna, whose task of providing a decent education is compounded by the fact that many students are only at the school temporarily, while many who leave will soon be back.

Principal Robert Patruna

“Heaps of them return,” says Patruna, during the morning break. “We just build on that from where we left off.”

He is sitting in a room off the central courtyard, accessed like every other space here via a heavy locked door. This room, however, is busy and buzzing, full of staff members sipping lattes and chatting over the constant drone of a coffee grinder.

With its hand-painted tables and do-it-yourself toast bar, The Hard Luck Café might not be Sydney’s most salubrious coffee shop. But it is one place that the boys who reside here can watch adults socialise, a rare chance to pick up some of the social cues so easily missed when you spend a part of your childhood locked up: how to talk to women, say, or how to order a cappuccino.

The Hard Luck Café

This morning, two older boys are making coffee while another studiously notes orders. They are overseen by a few teachers behind the counter and countless more sets of eyes from the handful of occupied tables. During their time at Reiby, all three boys have learned the art of coffee making, as part of their vocational training.

“Our aim at the end of the day is to make sure that they leave here and they are confident, lifelong learners,” says Patruna, a teacher for more than 20 years, as his order is served. He refers to the students as “our kids”.

“We want to instill in them that life is about opportunities and making the most of that.”

There have been some successes during Patruna’s three years here.

“We’ve got boys into uni courses, apprentices,” he says. One young man who had been here since he was 10 is now completing Year 12. But they are the exceptions.

“A success is a kid who doesn’t go out and punch his girlfriend in the head.”

“If you come in here thinking you are going to change the world, you are not going to do it,” says youth officer Regan Arthur, 35. In his six years working closely with boys at Reiby, he has learned to measure success on a smaller scale.

“In general, it’s just helping kids to be better human beings,” he says of his aim to change slight behaviours. “A success is a kid who doesn’t go out and punch his girlfriend in the head.”

The third boy is also 15. He is open and eloquent, unexpectedly thoughtful, even pulling out a chair so I can sit down. His dream was to become a V8 driver, a plan that was never fully explored until one day, when he had been here for a few months, a teacher asked whether anyone had considered university. No-one in his small, confined class put up his hand.

“I started thinking uni wouldn’t be a bad place to go to,” he says. He now plans to study business management so he can one day own his own restaurant.

But when he arrived at Reiby earlier this year, he was bewildered.

“I had no feeling whatsoever. It was like someone took away everything,” he says from his seat at a paint-splattered table in the art room. The back wall of the room is covered in pictures produced by his cohort. A bank of computers, with carefully monitored programs, has introduced some to the world of Photoshop.

But even in this environment, which encourages creativity, the loss of liberties remains profound. He misses spray-on deodorant and family and, as joyous as it is when a relative comes to see him each month and actually hugs him, and he can again enjoy the sensation of human touch: “When they’ve left, I am always down.”

And yet, life inside has not been as bad as he expected. He still wakes up most mornings and automatically goes to check that his parent is okay. He is an outdoor kid and being here makes him claustrophobic. But he only ever feels restricted when he reaches the perimeter wall, he says.

He has learned that his most valuable asset inside is his dignity.

“Honestly, it gives you a better understanding of the other boys, what they have gone through,” he says. “You think, ‘well, my life is the worst’ and then you come in here and you think ‘no, it’s not me. Everyone has a bad life’.”

Not all the boys hate living here.

“They feel safe, they get fed, they’ve got friends,” says acting centre manager Scott Harrison. “And they’ve got activities and school – and they don’t always get that in the community.”

He sees a multitude of children and a sad pattern of sameness. He has come to understand the enormous contribution of circumstances in the backstories of those who end up in his charge.

Against the length of childhood, a long sentence is seen as 2-3 years.

“Ninety-nine per cent of the time, I would say, they are not bad,” Harrison says. “Sometimes, it might be, a family seems fine and there’s been a death at a bad time and they’ve joined the wrong peers.”

Some stay for only hours before they are remanded. Many are inside for months. Against the length of childhood, a long sentence is seen as two or three years.

In his 20 years at the centre, the longest time that Harrison has seen anybody stay in Reiby is a decade (some boys who are over 16 are eligible to serve the remainder of their term here).

The fourth boy is 16. He returned here at 13 and has spent all his teenage years so far inside. In the two-and-a-half years he has been at Reiby this time, he has learned to lay bricks and make coffee. He has studied food technology.

“I could see straight away I was different to other boys,” he says of the regular visitors he has enjoyed in that time. “Some boys didn’t have much support from their families.”

This time, he has spent two Christmases and as many birthdays inside. He has missed weddings and countless other family celebrations.

“When you get a birthday in here, they say happy birthday and you get a cake,” he says quietly, detached. It’s never been even remotely like celebrating at home.

He is excited about adult life and getting an iPhone, but he is also scared to leave.

But life is about to change. In a few weeks, he is due to be released. In preparation, he has been moved into Reiby’s special pre-release unit, a significant privilege in an environment where even a bottle of shampoo is afforded the greatest currency.

For the first time since he was 13, he is living outside the razor wire. His home, for now, is a sort of share house on Reiby’s perimeter. It’s still under constant supervision, but with some notable benefits: carpet on the floor in his room, a kitchen for preparing his own meals, and a mostly open front door that is enabling him to slowly rejoin society.

He is excited about the possibilities that are now tantalisingly close: starting his adult life, learning to become a personal trainer and getting himself a new iPhone. But he is also scared to leave.

“Because I have been here, I have missed a lot of stuff, but I want to get out.”

When he came here at 13, the door was shut on Facebook and he had no idea about Twitter. Now, a different world awaits him and he worries about having to get used to new rules and other authorities, “and getting used to my own life, basically, and peer pressure”.

Unless he breaks any rules in the meantime (accessing social media, say) he will mark the New Year as a free young man. For the best of reasons, no-one at Reiby wants to see him again.