The operation is over before I even know what’s happened. Just a couple of tiny, strategic incisions and 4 year-old Aditya’s legs are already in plasters.

Braced for gore, I won’t lie, it’s *almost* a letdown.

“It seems so easy!” I yell, probably, definitely, offending the skilled orthopaedic surgeons in front of me.

Then it hits me – Aditya will now walk.

Without a trickle of blood, this operation has just changed his little life forever. And it almost never happened.

Parked at a train station in Latur, eastern Maharashtra, I’m aboard the Lifeline Express. A 90s-era train, it has mismatched carriages and two of them have been converted into state-of-the-art operating theatres on wheels. (“Like Darjeeling Limited meets ER!,” I later tell my boyfriend down the phone).

Painted sky blue with colourful flowers, the train travels to the most remote corners of India delivering medical care and surgeries to those who otherwise might never cross paths with a doctor.

For India’s poor, like Aditya, it’s a last chance and a glimmer of hope when hope has all but evaporated.

While India has a world-class private healthcare sector, it’s prohibitively expensive and urban centric. And even though the constitution enshrines free healthcare for all, in reality, millions slip through the cracks.

Close to a staggering 70% of people still live in rural areas where they have no or limited access to hospitals and clinics. Cut off by poverty or distance or both, even the most basic health checks are, for many, unimaginable.

Trikoli is one such place. Ignored by Google maps, it’s a tiny village where sacred cows wander empty roads and the grass is swept sideways by monsoon winds.

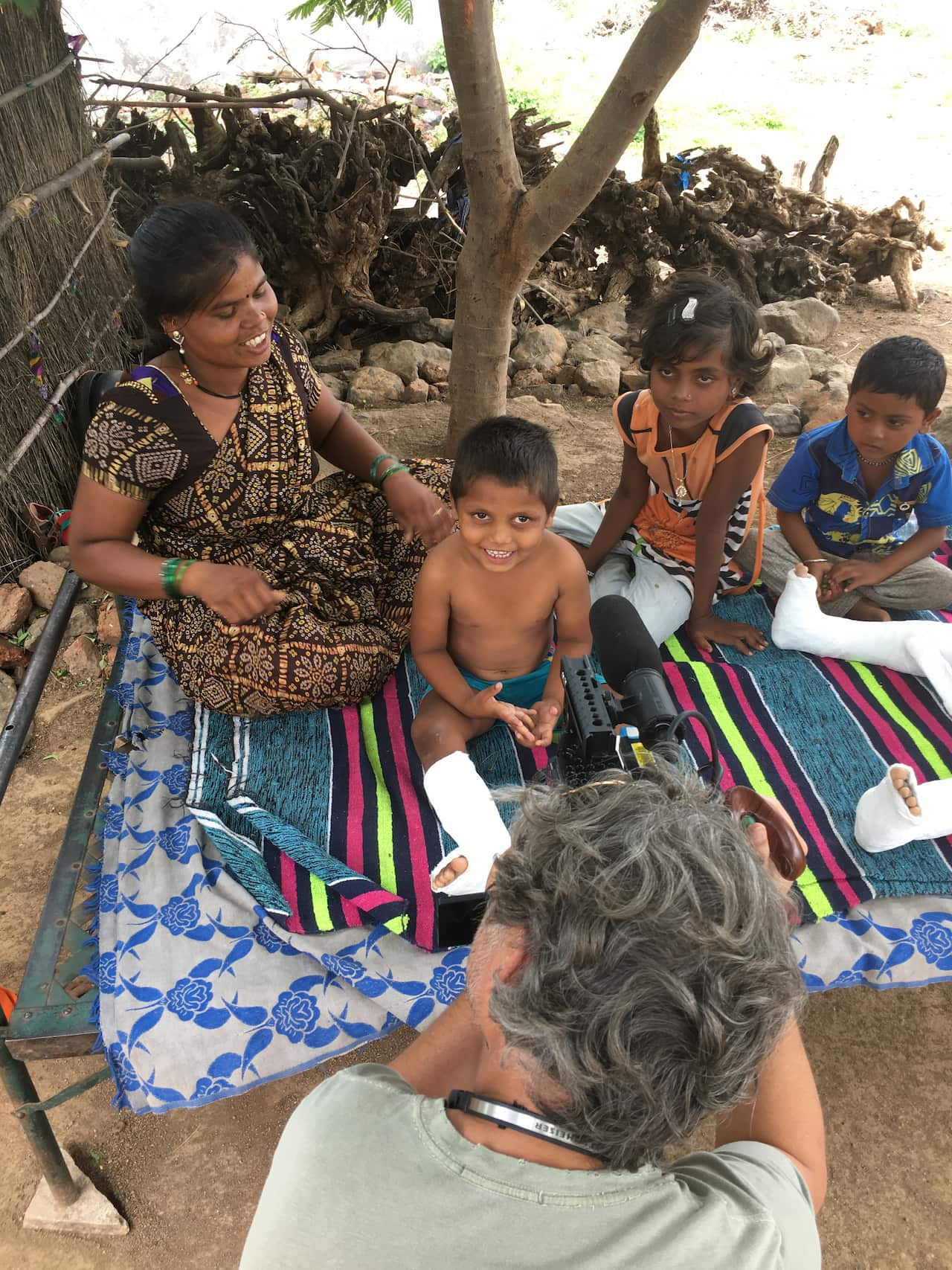

It’s also where Aditya and his older brother Virat, aged 7, have grown up with cerebral palsy.

Out here, their family watched on, as the muscles in their legs grew tight. Twisted and contracted, Aditya can barely walk on his toes when we first meet. Virat cannot walk at all.

Before the Lifeline Express, like so many of India’s 1.3 billion people, Aditya and Virat’s parents tried everything to help them - even though they’re already living below the poverty line.

“We travelled to so many places,” their father, Haridas, tells me. “Hyderabad, Umargaon, Solapur, we went to every clinic we could. We are daily wage earners – so whatever I earnt in the week was spent on travel alone.”

At home, Haridas tells me he’s borrowed money from others in the village. He owes close to $INR200,000 (almost $AU4000) and earns less than $AU3 a day.

One of the major reasons that India’s poor incur debt is the cost of health care. With the public system limited to cities and largely overwhelmed, its private practitioners who pick up the slack, meaning the already impoverished have to pay for treatment out of their own pockets. What’s more, in such remote areas like Trikoli, private practitioners can often mean quack doctors.

“We spent $INR3000 on different kinds of massage oil and tried it for a month but nothing happened. We were conned,” says Haridas, looking at the ground.

Having access to the Lifeline Express, then, is nothing short of a miracle. It performs all its operations for free.

Desperation and a little luck ultimately led Haridas to the train. Like everything in India, he found out about it via Whatsapp. On a trip to town, his brother saw a flyer for the train and texted him a picture.

Together with his wife, they travelled more then 4 hours from Trikoli to meet the train in Latur. Taking a series of buses and trucks, they carried Aditya and Virat the entire way. I imagine them piled in to the trucks that shuttle along India’s highways, overflowing with faces and limbs. What I can’t imagine, is doing so with two children who can barely walk.

It’s this context that gives the Lifeline Express its nickname: the magic train of India. Operations like Aditya and Virat’s are truly against all odds. Something that isn’t lost on their family.

Without the simple operation to release the tendons in their legs, Aditya and Virat’s bones would have eventually become deformed. Both would have been wheelchair bound by the age of 18– except, they wouldn’t even have a wheelchair.

When they instead return home with their legs in fresh casts, their faces are smothered in kisses and caresses.

“Did it hurt? Did you cry?” whispers their great grandmother, inspecting their legs, trying not to bump their toes. Crouching with her elbows on her knees, she wipes her eyes with the corners of a red and gold sari and begins to cry.

“It’s like our children have been reborn,” says Haridas, watching on. “All this happened because of the doctors’ blessings. They came to us like God and helped us.”

Update: Haridas recently sent Dateline a short video of the brothers beginning to take their first steps. Watch below:

Dateline is an award-winning Australian, international documentary series airing for over 40 years. Each week Dateline scours the globe to bring you a world of daring stories. Read more about Dateline

Have a story or comment? Contact Us