Peter Gett was born in the bush.

Arid earth lifts in gold clouds around his boots as he walks across his land.

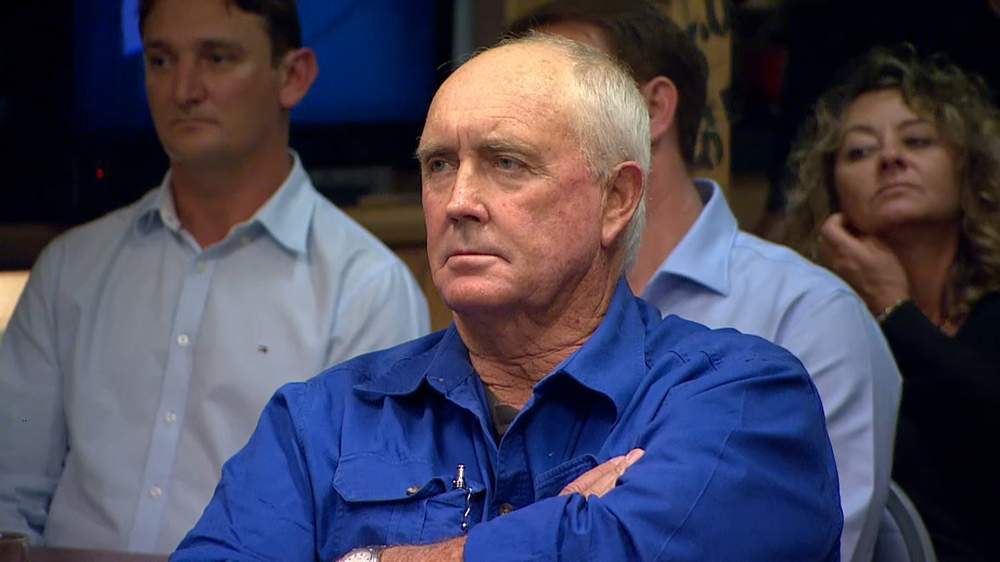

The 61-year-old believes farming is “in your blood.”

“We've been here in the district for over 100 years,” he says.

“My father took over from my grandfather. My brother and I have taken over from him. My son will be taking over from me and then my grandson’s coming along behind that.”

On Mr Gett’s property just outside Narrabri, in north-west New South Wales, cattle graze alongside rows of cereals. The typically inquisitive animals take little notice of the three coal seam gas wells hissing within metres.

Mr Gett welcomed oil and gas company Eastern Star Gas, and later Santos, on to his land more than a decade ago. He had always wanted to see what was under the ground and eventually got an answer: coal seam gas reserves.

Coal seam gas is mainly methane found within coal deposits trapped underground by water pressure. Drilling between 300 and 1,000 metres through layers of rock and pumping out saline water already in the coal seam lowers the pressure and releases the gas.

Coal seam gas wells outside Narrabri

Mr Gett’s wells have been exploratory, but are now ready for production. They are just a few of the 850 that gas giant Santos plans to drill in and around the Pilliga Forest.

The proposed project spans 95,000 hectares of land and Santos is awaiting state government approval to begin producing coal seam gas in the region.

Australia’s energy market operator says there could be a domestic gas shortfall on the east coast by 2019. Santos says the Narrabri project could supply up to 50% of NSW’s gas needs and deliver jobs.

Peter Gett has three coal seam gas wells on his property, located just outside Narrabri in north-west New South Wales.

The operations are fiercely contested across the state and beyond. The NSW Department of Planning received 23,000 submissions in response to the project.

The fight

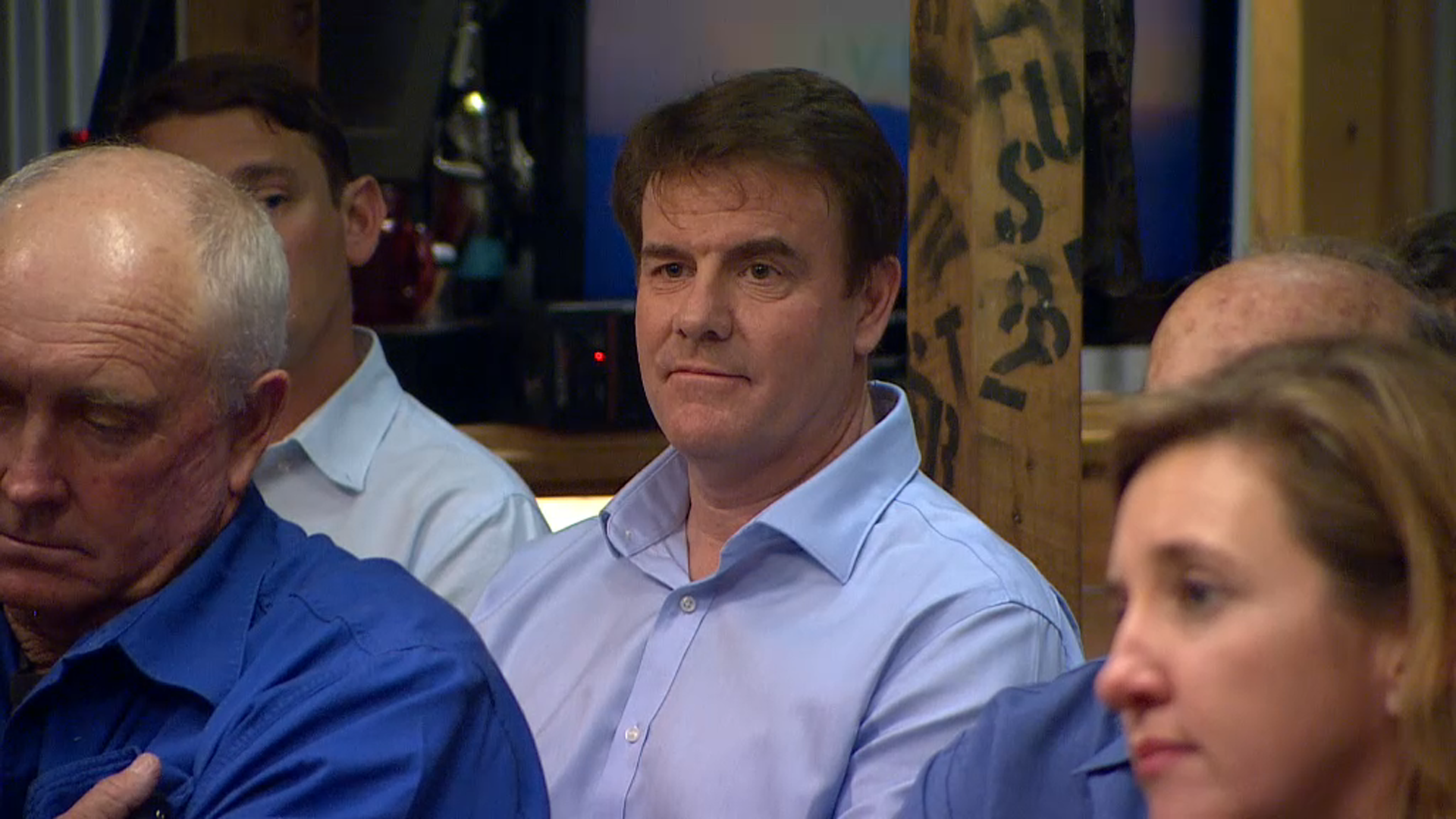

About 170 kilometres from Peter Gett’s gas wells live fellow farmer Adam Macrae, his wife Row and their five children.

The couple’s modest home, north of Coonamble, is powered entirely off solar energy. The floor inside is speckled with stuffed toys, the ground outside punctuated by children’s bicycles.

Energy infrastructure company, APA, is working with a Santos subsidiary to build a 461-kilometre underground pipeline to move gas from Narrabri to market.

The structure would cut through Mr Macrae’s land, which has been in his family since 1905.

“We want to leave this place in as good or better condition as what we found it,” says the 37 year old.

“That's at the heart of the issue.”

Adam Macrae, his wife Row and their family

Mr Macrae walks through the dried bed of the Castlereagh River while his children climb trees.

The location of the pipeline is also his access point to a cropping paddock he calls “one of the main economic powerhouses” of his business.

Mr Macrae lists his concerns about the project and its pipeline: soil disturbance, land clearing, restricted access to farmland, mental stress, and above all else, alarm over the very heart of agriculture – water.

“Water is the single thing that binds everybody in the community,” he says.

“We need the water that's under the ground - the great artesian water - and if that's in any way compromised, you're talking about the viability of entire communities.”

Adam Macrae, who owns a farm north of Coonamble in New South Wales, is concerned a planned coal seam gas pipeline that would run through his property could damage the water supply.

The Great Artesian Basin

In the 1800s, the European discovery of a vast water reservoir – the Great Artesian Basin – spanning one-fifth of Australia turned previously dry country to productive grazing land.

The below ground basin, which straddles Queensland, South Australia and New South Wales, stores 65,000 million megalitres of water. It could fill Sydney Harbour 130,000 times.

The first bore accessing the water supply was drilled in 1878. Within 30 years, 1,500 water bores had been sunk.

The sheer number of bores drilled caused pressure over the basin to drop and many required pumping or ceased flowing entirely. Since 1999, the Commonwealth Government has spent $124 million in conserving the resource.

Peter Gett has three coal seam gas wells on his property

In the coal seam gas debate, fears are often voiced about risking the Great Artesian Basin when water is removed from its coal seams.

Thick layers of clay typically separate underground water sources but a key concern is just how impermeable the barriers are and whether basins could be, or become, connected.

“The water thing is the main problem, the main worry with the people, that their water supply is going to be pumped out, dried up or contaminated,” says Mr Gett.

“It’s so far from the truth.”

Coal seam gas extraction can affect water in a number of ways: it could contaminate underground water if there’s a leak that enters a water source; affected water could travel between underground water sources; loss of pressure could cause fluid to move between connected underground sources; or it could contaminate the surface water that replenishes an underground source naturally.

Queensland v NSW

Seventy per cent of the Great Artesian Basin is below Queensland.

The state has commercially produced coal seam gas for almost 20 years, and with rapid growth of the industry in the last decade, it’s become the primary source of Queensland’s natural gas production.

In 2015, the resource began to be liquefied for export to Asian markets.

A 2016 Queensland Government impact report states water extraction for coal seam gas has increased to about 65,000 megalitres per year in the Surat Basin region, which forms part of the Great Artesian Basin, in eastern Queensland.

It also says of the approximately 22,500 bores in the region, 459 will have long-term effects from coal seam gas activities and 59 have already been decommissioned.

Professor Andrew Garnett, from the University of Queensland Centre for Coal Seam Gas, says the Narrabri area is less likely to experience the effects of extraction that were noted in Queensland.

“They’ve got higher risk of aquifer impacts in the Queensland geological scenario than in this geological scenario,” he says.

“Of course we're concerned about the water and everybody should be concerned about water and that's why you monitor it.”

Professor Andrew Garnett speaks on Insight about the effects of coal seam gas in Queensland compared to New South Wales

Mr Gett’s confidence in the Narrabri project rests on information he’s heard through hydrologists reports as well as Santos.

He did some land survey work in his early years and Santos formerly employed his son.

Mr Gett says the depth of the coal seams – which are between 500 and 1,200 metres deep around Narrabri – as well as the rock structure on top of them, mean the water used for stock and irrigation won’t be disturbed.

He feels the concrete and steel casing that clads extraction wells is sufficient in isolating the activities from the surrounding natural environment.

For Narrabri, Santos predicts change in ground water pressure will be less than 0.5 metres and bore owners won’t notice a change to their water supplies. The company also says it is drilling into the Gunnedah Basin, which sits below the Great Artesian Basin.

“The aquifers of the Great Artesian Basin and our target coal seams are separated by 250 to 400 metres of impermeable rock,” says David Banks, Santos Vice President of Onshore Upstream Projects.

Water produced from extraction will be treated so it can be re-used, while the salt by-product left over will be commercially sold or disposed of into a licensed landfill.

“We are looking at ways we could beneficially reuse the soda ash and other by-products, perhaps for the glass industry or for other industrial uses,” says Mr Banks.

David Banks from Santos appears on Insight

A CSIRO report predicts that while there will be changes to groundwater flow around Narrabri and the Pilliga Sandstone aquifer, which is part of the Great Artesian Basin, the affect will be minimal.

It predicts water loss from the Pilliga source will be about 0.3% of the annual extraction limit set by the regulator.

“The impact [from the Narrabri project] will be very small relative to other water users,” says CSIRO Research Director Dr Damian Barrett.

Dr Barrett from the CSIRO tells Insight coal seam gas extraction in Narrabri will have minimal effect on water

Dr Barrett says the average distance between underground water sources in the Pilliga region is about 6.5km.

“Water flows very slowly in the Pilliga Sandstone aquifer,” he says.

“The chance of wide-scale contamination of this aquifer is extremely low.”

It predicts water loss will be about 0.3 per cent of the annual extraction limit set by the regulator.

The concerns

The extracted water from coal seam gas reserves has the potential to cause environmental damage if leaked or spilled.

“Why would you compromise, not just agricultural businesses but entire communities and the water supply?” asks Mr Macrae.

In 2011, Santos acquired Eastern Star Gas and became the dominant coal seam gas producer from the Gunnedah Basin around Narrabri.

Eastern Star Gas recorded 16 leaks or spills between January 2010 and August 2011 in the area.

In 2014, Santos was fined $52,500 for failing to report a spill relating to coal seam gas operations around Narrabri. The company released a statement saying the offences occurred prior to their acquisition of Eastern Star.

The CSIRO says hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is used in up to 40 per cent of coal seam gas wells in Australia.

Mr Macrae says environmental sustainability is core to his farming business

“One of my pet hates is fracking,” says Mr Gett, who also believes in climate change.

“But this new technology they've developed here does away with fracking in this area.”

“They’re not going to use it underneath my land. That’s the main thing.”

Fracking involves injecting fluid made up of water, sand and chemical additives under high pressure into the coal seam.The pressure creates a fracture that allows gas to more readily escape.

When used in larger operations, fractures can spread to 300 metres from the well shaft.

While some question whether underground water sources will remain separated when fracking operations are used, in Narrabri, Santos says it has “no plans” to frack and is not seeking approval to do so.

Mr Gett’s wells are drilled horizontally, which increases access to the coal and trapped gas and often means hydraulic fracturing isn’t needed.

However, a University of Queensland review of the drilling technique in NSW found it can make sealing a well more difficult and can increase the risk of leaks, unless controlled.

Divided

Initially compensated about $1,500 for the use of his land, Mr Gett now receives more than $30,000 a year from Santos.

“I haven't used it for any overseas holidays, or expensive motorcars or whatever,” he says.

“We've used it to put in to our farm a bit of haymaking equipment and we've got a far better watering system for all our stock. Especially when all our dams are dry, we've still got good water.”

Mr Gett now has a fourth pilot well in the works on his property.

Despite their difference in age and in opinion, Mr Gett and Mr Macrae can agree on one thing – farming conditions are tough.

“Every season seems to be a bit harder than the last,” says Mr Gett.

Both men say meaningful rain hasn’t fallen for years.

“It's as bad as I've seen it here,” echoes Mr Macrae.

Mr Macrae says he hasn’t received information showing the pipeline project is safe or environmentally sound.

In addition to the pipeline, he’s alsoworried that a current Santos petroleum exploration license that covers Coonamble could lead to coal seam gas extraction like that in Narrabri.

“The challenge has been to try and help our community get the answers and the assurances that it's going to be okay,” he says.

“If we don't tackle it…don't seek the answers, don't push for the accountability that we're pushing for, no one else is going to do it.”

“No one else is going to do it for our kids.”

Santos says it is not planning to expand the current project beyond the Narrabri region.

A special edition of Insight travels to Narrabri to hear from those who may be affected by the project and its infrastructure.