From the 1950s to the 1980s, it was not uncommon for young mothers forced to give up their children in the face of societal and family pressure.

The practice of forced adoption was widespread - thought to have affected 1 in 15 Australians - and its impact on the physical and psychological health of young mothers and the children they gave up, devastating.

Now, a University of New South Wales study is looking to shed light on the other side of that experience: the young fathers who had little say in their child’s adoption.

But in the study’s preliminary two years, assistant researcher Paul Cornefert has only been able to bring a dozen men to the table for an interview.

“It’s really difficult identifying them and getting them to come forward,” he explains.

The study wants to get behind that steely masculine veneer to find out about the feelings and experiences of birth fathers who have gone through the adoption process.

In 2013, then Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, apologised to the hundreds of thousands of parents who had been forced to give their children up for adoption.

From the 1950s up until the 1980s, it was common practice to remove children from their parents who were deemed too young or ill-prepared to raise their child out of wedlock. Much of the focus since then has been on the mothers and the trauma they experienced having their baby taken from them. Very little, however, has been done to understand the father’s side of the story and how it has affected them.

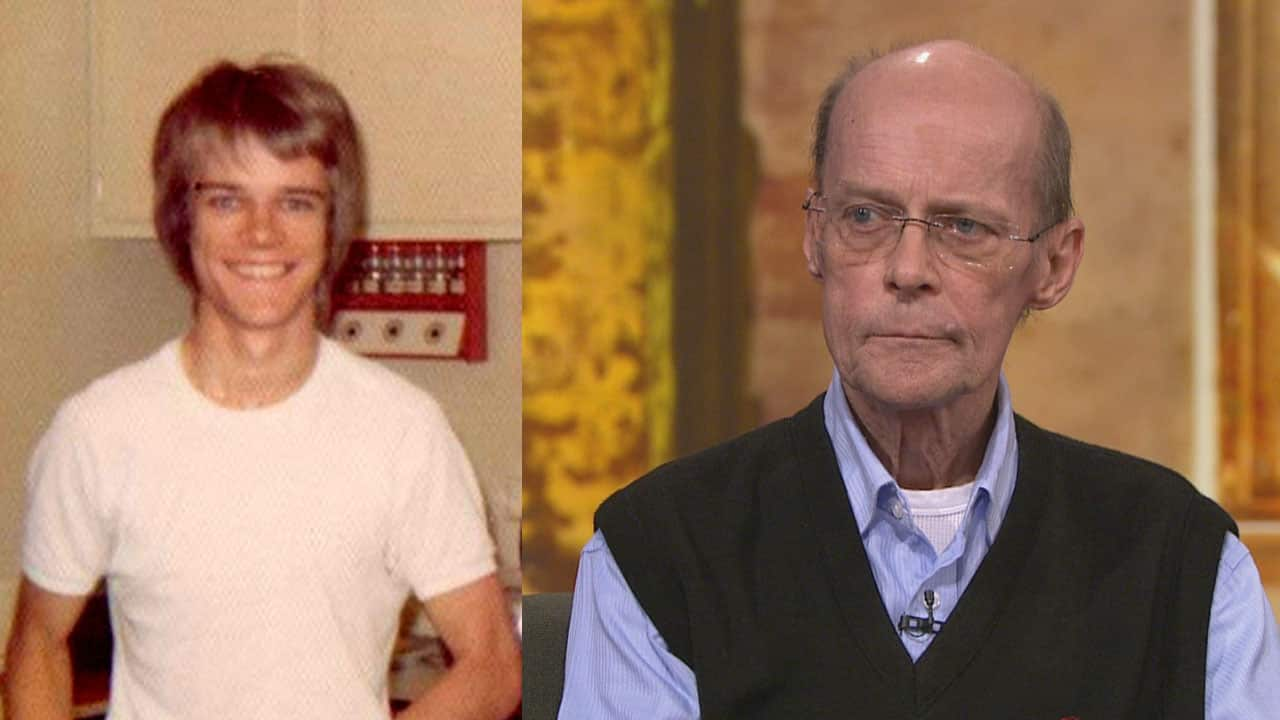

“I wasn’t consulted at all, it was like I hadn’t existed,” recalls Gary Boyce as he reminisces the events of 1972. Back then, he was 19 when his girlfriend gave birth to a baby girl. “The decision was made by Jane’s parents that the child would be adopted,” he says on this week’s episode of Insight. The baby girl was taken away before he could ever lay eyes on her.

Ken Lumsden only found out he was a father after his daughter, Emma, was born in 1979. His girlfriend’s parents refused to allow him see her and she never told him she was pregnant. Life moved on for Ken as he found a wife and had other kids. He never looked for Emma but never stopped thinking about her either.

Emma Law grew up wondering about her birth parents, “I could never understand why my birth parents gave me up. Did they want a boy? Or girl with blonde hair? Was there something about me they didn’t like?”

Reconnecting with her birth mother was possible because her name was on the birth certificate. Her birth mother had no information, other than a name, of her father though. She eventually found Ken last year and they have been close ever since.

Gary’s name was also omitted from his daughter’s birth certificate, making a potential reunion with her all the more difficult. This was the practice in the vast majority of adoption cases before the 1980s.

“Many mothers say even if they wanted to put the father’s name down they were discouraged. Pregnancy was seen as a woman’s responsibility. It was seen as unfair to put the father’s name down. It would sully his good name. There are sexist reasons for this,” says Darryl Higgins of the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Higgins and the Institute of Family Studies were behind a landmark study in 2012 that looked into past adoption experiences. They wanted to hear from all perspectives and spoke to over 1,500 people. Of that number, only 12 fathers were willing to participate.

Cornefert hopes more fathers will come forward to share their experiences, hoping the study will expand knowledge of this issue.

“There is little known about the feelings and experiences of Australian birth fathers about the process of their children being adopted… it can cause lifelong hurt.”

For more information about the Birth Fathers study at UNSW, visit their website.

Insight: Forgotten Fathers | Catch up online now:

[videocard video="705552963527"]

Insight is Australia's leading forum for debate and powerful first-person stories offering a unique perspective on the way we live. Read more about Insight

Have a story or comment? Contact Us