Dowry or bride price practices are alive and well in Australia, not only in sections of the Indian community, but amongst the African and Islamic communities too.

In Melbourne, 25-year-old South Sudanese man Chol Goch was proud to negotiate and pay a high price for his new wife, Ajah Wuoi.

“It’s alright because that’s what I want. If I get her, doesn’t matter, I would pay a million bucks if I had a million bucks,” Chol says on Insight.

Ajah grew up expecting a dowry and felt more respected by her community after she recently brought the high price of $70,000.

“It shows how much he respects your family and how much he loves you so much because it’s not easy to give a dowry like that you know. But they have to do it, especially when you love the woman and if you want that girl to be your wife,” says Ajah.

Salpha Dut, from the same community, has been working 11 hours a day, seven days a week for the past two years in Hobart to save up for his wife who is waiting for him to afford a dowry of 250 cows before her family will let her move to Australia.

“Whatever hours I could get my hands on I’ll take it because I want to save up for my wife,” says Salpha.

Despite the hardship, Salpha doesn’t have an issue with paying a dowry.

“I don’t have a problem with it because that’s the price for a wife. My father paid, my grandfather paid, I have to pay for her because I would feel really, really bad to have someone’s daughter without paying,” he says.

But not everyone within the community is happy to accept the traditional way of doing things without challenging it. South Sudanese lawyer Nyadol Nyuon is against dowry and says it promotes gender imbalance.

“I think that a younger generation is attempting to find a middle ground where we don’t push away our elders but at the same time we’re able to live I suppose a much more decent life or life that recognises women as equals,” Nyadol says.

She’d like to see it abolished but she recently married and accepted her husband paying a large price for her to keep her family happy. She says this highlights the cultural clash within new communities in Australia as they negotiate old traditions in a new setting.

“I feel very conflicted and I felt as if I wasn’t strong enough to have stood up to my culture and say I actually don’t want him to pay this amount of cows for me,” she says.

In Sydney, Sheron Sultan, a model from a South African background, asked her Austrian boyfriend Nick Toth to pay lobola, the bride price, as she wanted to uphold her culture and keep her ancestors and family happy. But the couple struggled with the concept of paying for a wife until they interpreted the tradition in a new way to make it their own.

“I had told my parents that I’m not going to let me uncles decided how much I am worth," says Sheron. "I mean it’s a great gesture, I love it, I respect my culture, it has formed my identity. But at the same time I am marrying someone out of my culture so therefore I have to respect his side as well." Similarly in Brisbane, Naseema Mustapha personalised her Islamic dowry by requesting her husband-to-be, Mohamed Bah, to buy and slaughter a goat to cook it and feed the poor.

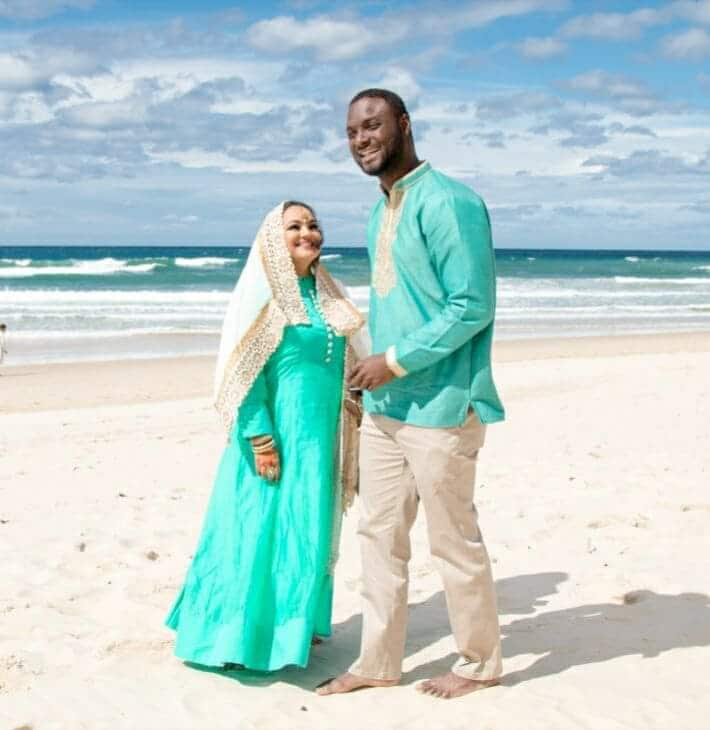

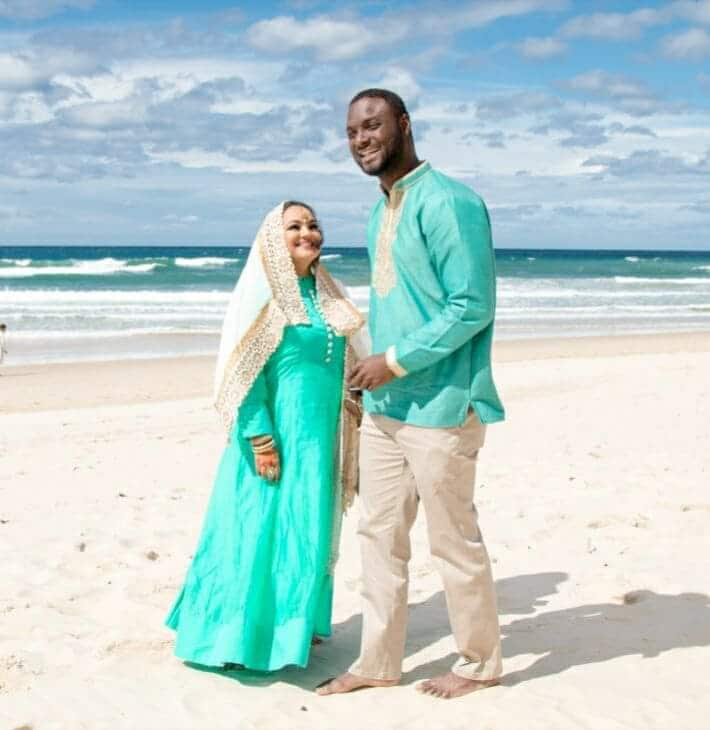

Similarly in Brisbane, Naseema Mustapha personalised her Islamic dowry by requesting her husband-to-be, Mohamed Bah, to buy and slaughter a goat to cook it and feed the poor.

Naseema and Mohamed on their recent wedding day. Source: Supplied

“Every Muslim who gets married, if they’re having an Islamic ceremony, it’s a condition of the Islamic ceremony. So everyone I know who has a Nikah does a dowry but it varies tremendously,” says Naseema.

Some have experienced the darker side of dowry. Roopa*, a 24-year-old Indian woman living in Melbourne, describes how the Indian dowry custom destroyed her arranged marriage. Roopa was a student when she first met her husband in Melbourne after their parents fixed the marriage in India. Everything was going smoothly until the day after the wedding in India, when she claims her in-laws and husband started demanding money from her father.

“It was shocking for me when he suddenly changed,” she says.

Roopa says her husband’s family demanded money and goods from her family in India and threatened their son would’nt speak to her until her father paid them.

“It has affected me like it has stopped my life. I can’t trust anyone,” she says.

*Name has been changed.