Listen to Australian and world news, and follow trending topics with SBS News Podcasts.

TRANSCRIPT:

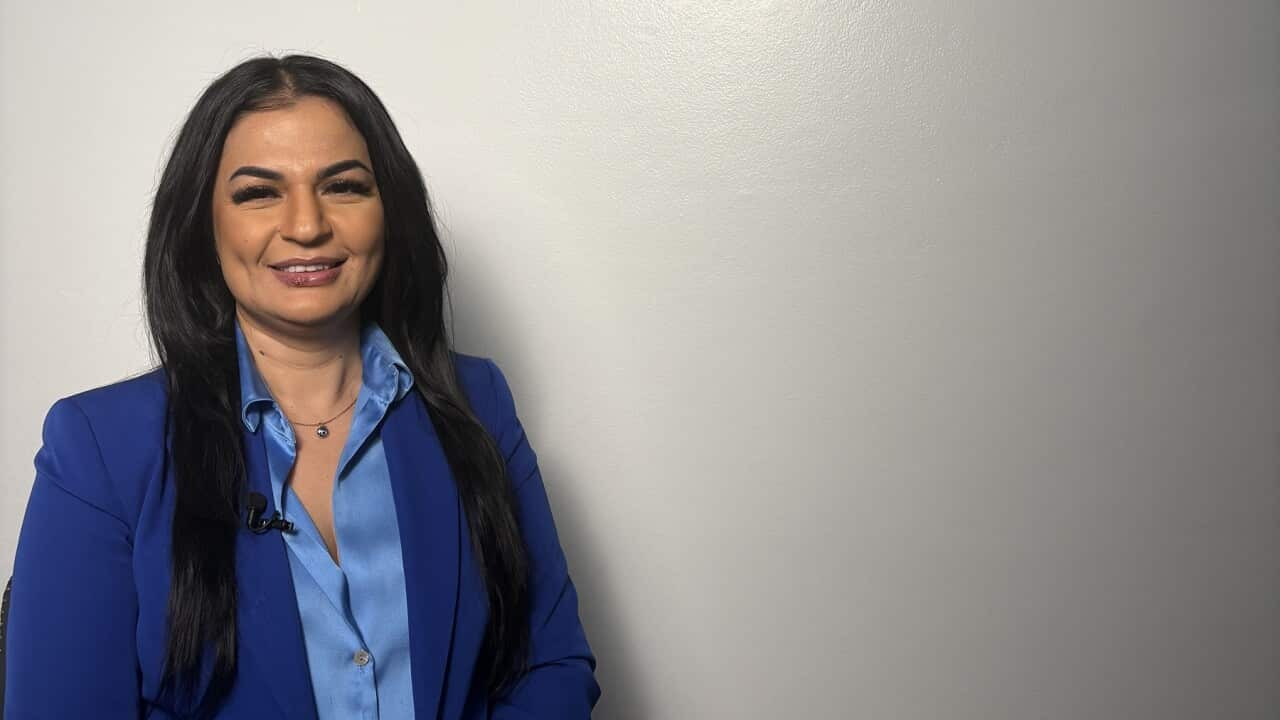

It's been more than 25 years since Tahera Nassrat was forced to flee Afghanistan.

"I was working with Medicines Sans Frontiers, and that's where we had to evacuate and leave Afghanistan, not by choice. We were forced to evacuate and leave."

Fearful that her work with an international organisation would make her a target for the Taliban, she initially fled to Pakistan.

"I was so scared, of course. Because I'm a woman, and it's against Taliban belief, you as a Muslim woman, you can't work with foreigners. I had to leave family, friends, country, memories. Everything you believe is yours, you're forced to leave. I left the country not by choice, but because I was forced to take leadership on my life from a very young age."

Her journey as a refugee eventually led her Australia, and Tahera now lives and works in Parramatta in Western Sydney as a tax accountant and business coach.

She's the founder of the Afghan Peace Foundation, an organisation that provides financial guidance and employment support to others from refugee backgrounds.

"We do a lot of employment for refugees to connect them to the jobs. Of course when a refugee comes to a new country, they're faced with a lot of trauma. My involvement is to educate."

She's one of almost 1 million people to settle in Australia through the country's refugee and humanitarian program since the end of World War Two.

Director of Policy and Research at the Refugee Council of Australia Rebecca Eckart says the millionth permanent humanitarian visa is expected to be issued imminently.

"We believe that about 998,000 visas were granted up until June of this year. So we do expect that over the coming months, that millionth visa will be issued. And that means we'll have had the benefit of over the past 80 years, people who have come through our refugee and humanitarian program arriving in Australia."

In the five years after World War Two, Australia welcomed over 170,000 European refugees.

The Vietnam War also prompted a large-scale response, with 100,000 settlements over 10 years.

Annual intake was expanded to 22,000 in the 1980s, and in the 1990s, a new Special Assistance visa was introduced in reponse to conflicts in former Yugoslavia, East Timor, Lebanon and Sudan, among others.

The focus then shifted to support refugees from the Middle East, Africa and the Asia-Pacific, including a special annual intake of 12-thousand Syrian and Iraqi refugees from 2015.

Ms Eckart says nearing our millionth humanitarian visa is a reminder of the diverse individual stories that make up this history.

"Today there's millions of people who are connected to our humanitarian program, either directly or through their parents, grandparents, or great grandparents. It's a really momentous time.”

Professor Daniel Ghezelbash is Director of the Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law.

He says the milestone also offers a chance to reflect on how Australia can improve its response to global displacement.

"Look, I really think it's a cause for celebration and a moment to mark the transformative contributions that refugees and their families have made to our society and our economy over many, many decades now. But also to use this moment to reassess some of our current approaches and to try and return to our better instincts."

Australia's humanitarian program intake is made up of two key groups.

Between 1947 and 2023 most permanent visas - more than 850-thousand [[876,851]] - were issued to those who applied for protection from outside Australia.

Just over 81,000 [[81,183]] had been issued to those seeking protection after arriving in Australia.

Professor Ghezelbash says Australia's approach is not consistent.

"I think our relatively generous resettlement program stands in great contrast to the way we treat asylum seekers. And so I think that's really the room where the biggest concerns and the biggest criticism of our policies come from."

In 2001 Australia implemented a policy of offshore processing for asylum-seekers arriving by boat, and the law was amended in 2013 to prevent boat arrivals from ever gaining permanent visas.

The offshore processing policy has received bipartisan support since 2012 - but Professor Ghezelbash says Australia's asylum policies have been the subject of widespread international criticism.

"The policy of pushing back asylum seekers at sea have essentially completely shut off access to asylum for people who arrive without authorisation, which are actually the people who are generating most need of protection. And so these policies just aren't unlawful under international law. They're incredibly harmful for the people that they target."

As Australia prepares to welcome its one millionth refugee on a permanent visa, he says there is cause for celebration alongside urgent calls for reform.

"I think we need to reflect on the ways we can better balance the legitimate concerns about border security with providing people access to protection at a broader level. What these policies do is they send a really bad signal internationally and Australia should be a leader when it comes to promoting protection, but in fact, we've been doing the exact opposite, setting up these models of deterrence, which have been emulated around the world."

Ms Nassrat says a shift in narrative is needed so that those who seek protection are no longer seen as a political problem.

"I hear people say 'oh you're a refugee, you're always a burden to the government. I'm here, sitting around the same table as you, I'm contributing. Refugees come to a country like Australia, as they do to any other country, with a rich culture, with capability, with responsibility. They want to contribute."