Listen to Australian and world news, and follow trending topics with SBS News Podcasts.

TRANSCRIPT

For most of Australia, it's just a regular Monday.

But two hours drive from Melbourne, the small country town for Morwell is buzzing.

Erin Patterson is about to take the stand and Anita Lester is getting ready to capture that moment.

"I was actually in a media room for that one, which is an offset room from the actual window that she was sitting at. The reason being is this particular case has just captured the nation. It's like a full on folkloric story that people have really attached to. So, I don't get in very easily. I walk in, there's only reporters in this room, and I was very lucky, they gave me front and centre seat."

The Mushroom Trial amassed a global following, with Patterson facing three counts of murder and one of attempted murder after serving her former in-laws beef wellingtons containing death cap mushrooms in 2023.

On this not-so-regular Monday, Patterson is getting ready to testifying for the first time.

"The adrenaline is so high when the suspect walks out onto the stand. You suddenly get mounted with so much pressure. You don't anticipate. It doesn't matter how many times you've drawn someone in real life, and you have to kind of block out the noise."

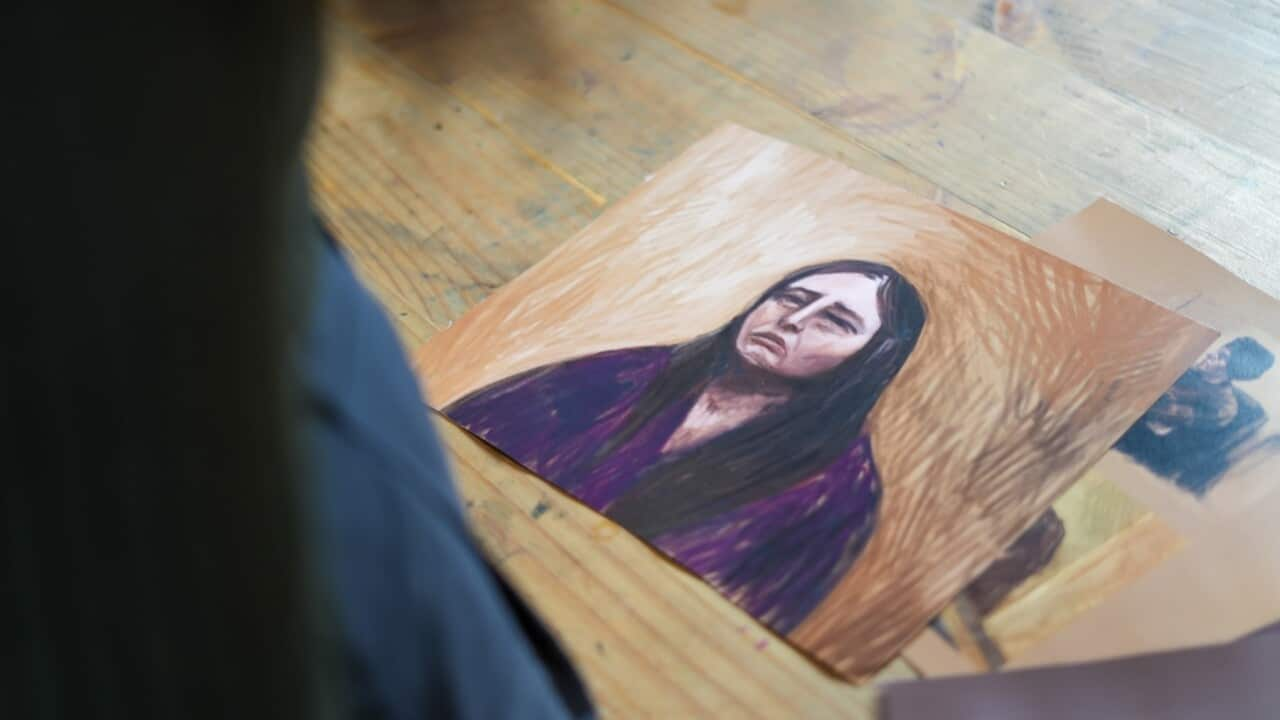

Ms Lester's sketchy picture of a distressed Erin Patterson will become synonymous with the Mushroom Trial.

But it's not the first she has been a part of.

The musician and visual artist's first stint in a courtroom was in 2023 for the trial of Malka Leifer... a former school principal convicted on 18 counts of rape and child sexual abuse.

"I have a relationship with a newspaper that just invited me to do it on a whim. I hadn't really known any of the technicalities and thought it would be an interesting experience. I was really lucky the surrounding publications, outside of my commissioning editor, were really interested in my piece and syndicated it. And then I started getting calls from all the different networks, and now I seem to be one of the first people people call."

Since then, Ms Lester has drawn other high-profile figures including notorious gangland boss Tony Mokbel, and accused Easey Street murderer Perry Kouroumblis.

Courtroom artists are commissioned by media outlets, called in during key moments in high-profile cases.

Cameras are banned in most courtrooms in Australia - so those images, those drawings, are still the only peek inside most people will ever get to see.

"The art of courtroom drawing started in the 1700s where people would go to public hangings and draw the people being hung for newspapers and because it captured the essence of the story, it became a tradition. Now to protect the the rights and the privacy of not only the people on trial in very vulnerable situations, but also the jury, they've been able to retain the boundaries around what is allowed inside and outside of court. I'm just so happy that I'm involved in this very old tradition, because it's so magical in its own way."

They often have just minutes with the subject - as was the case when Ms Lester first drew Patterson at a filing hearing in 2023.

"This is prior to the frenetic energy around the case. There was already a lot of interest in the case, but I arrived there, I had a really great seat in court. She walked out for two minutes. I had to draw her and and then the court room proceedings were postponed for months."

When Patterson took the stand this June, Ms Lester had more time.

"I watched her speak for about 20 minutes, which meant that I had, realistically, about 10 minutes to draw her. A lot of people who draw from life, they develop their own techniques of snapshotting people's features in their mind. It helps them recount them, contextualise them. So I tend to stare at the suspect for about a minute before I do anything. I just like, snap, snap, snap, snap, and then I do my base sketching. So I just like, do the roughest, ugliest sketch you've ever seen, just to put things down on the paper, and then it's a process. It's like kind of a meditation. You have to try really hard not to listen to what is actually going on in the courtroom. Sometimes the details are quite interesting. Sometimes they're quite in full on, often a little bit traumatizing. And then the process just goes and you have as much as time as you have. And what usually happens is the courtroom closes, I run outside, I find the closest seat, it's usually directly outside of the courtroom, and I put on headphones, and I just draw and finish the drawing, retaining the information that I've collected in those minutes."

RANIA YALLOP: "So what medium are you using to do the drawings?"

ANITA LESTER: "I think I'm one of the first people in Australia that was granted access for a digital medium, which is so lucky. I don't think it would be that possible to do it with watercolor or pencil. A lot of people do. Ideally, I would love to do that, but it's so impractical in that setting. The first time I was in court, there was someone who had this amazing, little portable station, but I was looking at him half the time thinking, what a nightmare like I'm so happy that I have this option.

RANIA YALLOP: "What do you think the pros and cons are?"

ANITA LESTER: "You never can recreate the emotive quality of paint and pencil. I mean, there's just nothing like it. I try my very hardest to emulate the textures of what I might be using in real life. I thought about this a lot, especially after my first few sittings, what would I ideally like to be using? And it sort of just was so clear to me that it was pastel and charcoal. So I have designed my own brushes on my digital platform, and they have a trail of dust, digital dust, so they do actually look a little bit like charcoal."

RANIA YALLOP: "What are you trying to capture? Is it like you're trying to get an exact image of what's there, or is there more to it than that?"

ANITA LESTER: "I think definitely not. I think, if I'm being critical about my earlier drawings, I was fixating a lot on trying to get accurate representations of the person. You definitely need to get a likeness that is, without a doubt, the main priority. But I think what has resonated about my work, if I can be kind of self observant, is that I am focusing mostly on the gesture and the emotion of the sitter. So perhaps why this particular drawing that I've done of Erin is has been so visceral for people, is because I captured her misery, I thought. And then it seemed like people also had that experience of the of the image. And just like, as a side note, I was sitting there and she looked so curmudgeon the whole time. And I was thinking, Ah, do I? Do I give her the frown that I am seeing? And I, and I kind of concluded that, yes, that was the right thing to do, and you don't cheat the details. That's that's sort of like what I think you have to be as honest as you can. One thing that has been asked of this drawing is, where is her famous, tiny neck, or a big chin, if I'm being polite, double chin. And the truth is, it was obscured by a shadow. So I could, I could have drawn her double chin, but it would have actually taken away from the integrity of the image, which is why you have a courtroom artist, so they can recount what they actually experience. You do have to put on your journalist hat a little bit when you're doing courtroom art, because you're you are giving the people what they want. You're giving them this experience that you're having, but the experience of the story that is being told as well. So you know, when I spoke about Erin's frown and her sad, the sadness in her mouth, there was a moment where I could have opened her mouth a little bit. She definitely was animated. She was talking enough that I could capture a moment where her mouth would have been more straight, but I felt as though it would be a more fascinating proposition for anyone looking at the drawing to exaggerate the emotion that I was feeling and that I was capturing. So you are part journalists, part artist in that setting."

The Patterson piece stands out from Ms Lester's other work.

All her other courtroom drawings include both the person and the surrounding courtroom... with microphones, glass screens, sometimes detailed paneling on the walls.

But this picture of Erin Patterson is just her, centred in the frame, with a loose, sketchy background.

"So do you know how I was telling you that trying to get a realistic likeness was a mistake that I sort of made early on?"

RANIA YALLOP: "Yeah."

ANITA LESTER: "This is a really good example of that. As much as these drawings are effective and they the details that capture the courtroom well, I feel like I missed out on capturing the emotion of the sitters. With these two sitters, uniquely, I only had 10 minutes with each of them. So what I generally did was I'd draw the surrounding area. I would spend quite a bit of time drawing the box, the glass."

RANIA YALLOP: "Because they weren't in the box already, you kind of had more time to do the box and then add them in afterwards?

ANITA LESTER: "Correct, yeah. So this one, I made a decision not to put in her microphone and the background. I just felt like I just wanted to focus on her. She was so distressed this day in court, I actually felt a bit bad for her, if I'm being totally honest, controversially. I just wanted to focus on her. I wanted to take away any distractions, I think emotionally, a lot of the time, if I do a lot of the surrounding imagery, there is a level of like me, kind of protecting myself a little bit, focusing on other things. Yeah, like I said, it can be quite intense, actually, the process of drawing, I'm not very sensitive, but it can be."

RANIA YALLOP: Are there things that you're privy to in court that you can't recreate in those artworks?

ANITA LESTER: "You learn a lot about the people on trial during these appearances, especially some of the more high profile cases you read about, and you come in with this pre conceived idea about the person, I think going back to the humanity of the experience like I think what people don't realize when people are on trial, they're terrified. They're being put under a microscope like that could be the guiltiest person in the world, don't get me wrong. And there have been experiences that I've had where the person on trial is so clearly not a good person, but when the lines are a bit blurred, you are privy to seeing something more vulnerable and like, almost like childlike a lot of the time. So that's one really interesting dynamic."

RANIA YALLOP: "Do the accused ever notice you?"

ANITA LESTER: "Oh yeah. Oh yeah, yeah. That is the weirdest part of it I think. You often get stared down for most of the for most of the trial. Marco lifer stared at me for probably two hours. I was sitting as far as I am from you, turned back at her because she was behind me in the courtroom, and she was just eyeballing me the whole time. And it's very unnerving. So was Tony Mokbel. I was standing, I was the sole figure through the doorway, and he just would look at me constantly."

RANIA YALLOP: "This is, you said before, you know, one of the biggest news stories, one of the cases with the most attention in decades in Australia. How does that feel to be involved in it?"

ANITA LESTER: "It's very surreal, actually. That drawing that I did, that is now everywhere, I got the call, I was in a court one hour later, and two hours after I got the call, it was in the papers already. So that's the turnaround, and that was just a tiny little snippet of my life, but now I'm intrinsically tied to this conversation. It's wild, it's two hours of my life has become the thing that I am now associated with, which is so weird. But, you know, people are doing their own versions of it and filming it and doing homages to the drawing. And I'm getting fan, you know, fan DMs and heaps of people like, I probably get something about it every day, like, can you tell me something about the court and you know, like, Do you have any details that you're not allowed to tell? Which is just such a silly question that I get all the time, maybe this is my chance to say I am not going to be in contempt of court, so don't ask me questions."

In a time when information and photographs are abundant, Ms Lester says there's something about court art that makes people slow down.

"I have become really interested in courtroom art since kind of going down this journey. I think my favourite pieces are not the ones that look exactly like the person on trial. I think they're the ones that capture movement, that capture the emotion, and, more importantly, that capture the humanity of the person on the stand. I think that we take photos for granted. And I think the reason why art is such a pure expression of a person is because it's not this normal consumption of an image we are seeing, something that we recognise, but is different, and it's emotive, and it's a moment that's really like tangible."