Listen to Australian and world news, and follow trending topics with SBS News Podcasts.

TRANSCRIPT

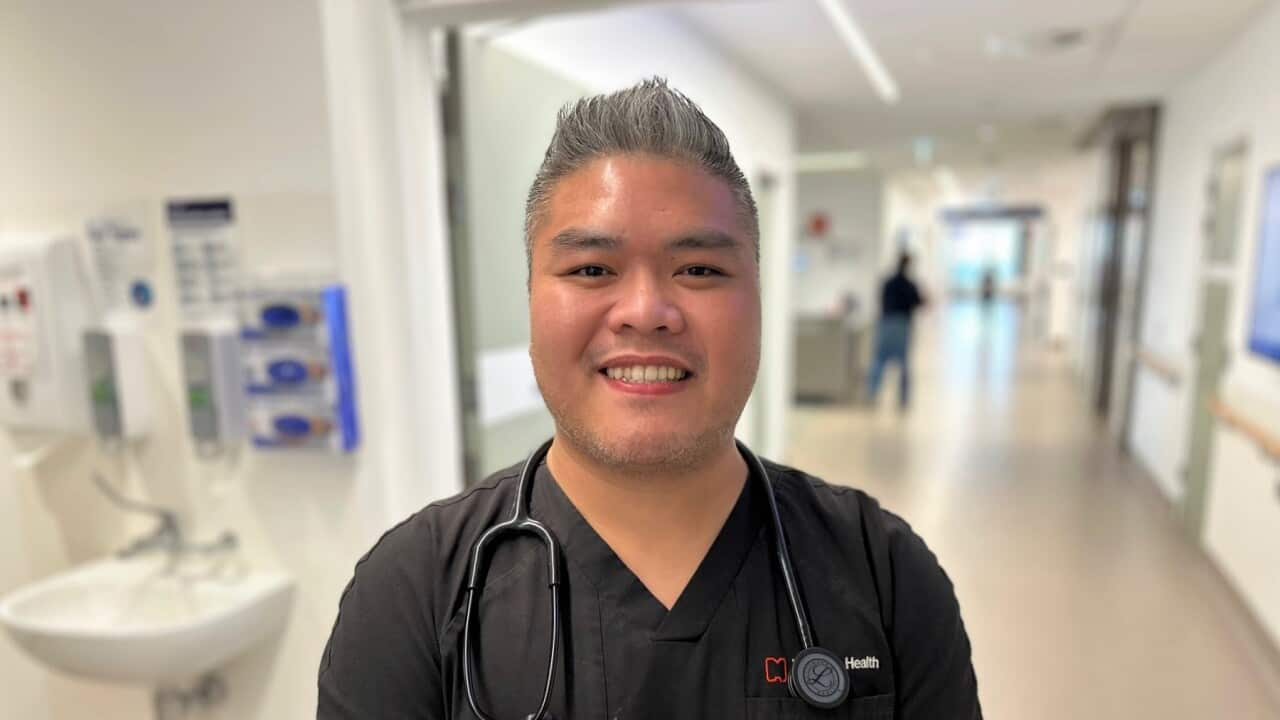

Khoa Nguyenworks as a critical care nurse at a major Melbourne hospital. The 31-year-old is incredibly proud to help save lives on the medical frontline.

“It is rewarding but challenging at the same time. I love the fast paced, rapid response that you could do to help the patient to be back on their feet.”

But his journey to the Victorian Heart Hospital was anything but smooth. During a gap year to earn money for university fees, Mr Nguyen took a labouring job on a farm in South Australia.

“So we would get up at four, so getting ready and we'd be at the farms around 5, 5 30. Sometimes it's raining and it's hot as well. But yeah, I didn't want to take the break and I just had to keep going because otherwise I wouldn't get paid that day.”

Mr Nguyen shared a trailer with several others, working long hours for perhaps a few hundred dollars a day. Even then, he said his wages were docked -- allegedly to pay for upfront costs.

“They already said we provided you with all the equipment all the safety gear, accommodation and then that's deducted from your salary. The accommodation and the equipment couldn't cost that much - but I didn't know where to seek help so I just agreed with that.”

What’s worse, he says when the workers asked for their full wages the contractor paid only part of the money owing.

“He said we'll keep it here just in case you break equipment and you do something to the accommodation, as well as the bond. And they said after the season then we'll pay you back. When the season finished and we asked for the money to come back and they said ‘okay, I'll give it to you next two days’. And he just took off.”

Mr Nguyen said the group had little money left for fares home or to buy food.

“We drink plenty of water just to feel our stomach and survive because we got no contact, we didn't know where to seek help. I was stuck there two-and-a-half months. Two and a half months I had to stay in the trailer.”

Mr Nguyen reckons he was owed up to $10,000 in back pay. He doesn’t recall the name of the contractor nor has he tried to recover the funds.

“During that period I thought of giving up, I thought ‘oh this is not for me. I don't want to continue anymore. This is so hard for me’.”

It’s an all-too-common problem, according to Associate Professor Bassina Farbenblum ((BASS-in-ah Fahr-ben-bloom)) from the faculty of law and justice at the University of New South Wales and also co-executive Director of the Migrant Justice Institute.

“We have a pervasive problem with workplace exploitation for international students and people working on temporary visas in Australia. Migrants are especially vulnerable. So, for international students, they want to stay and finish their studies. And so employers know how desperately they need to protect that visa and how much they need their job.”

It’s not just international students who struggle.

A University of Melbourne survey of 2,800 young workers released in July this year found that one third were likely underpaid, two thirds were forced to pay for work-related items such as uniforms or protective equipment, almost one-third were not paid compulsory super. Associate Professor Farbenblum says information is key.

“Fair Work Ombudsman's website has some really good resources and that includes working out what your hourly rate is. If you are not getting leave, so if you're not getting sick leave and holiday leave, you're probably a casual worker, which means you're entitled to a 25 per cent loading. And then if you're working on nights and weekends, you might be entitled to penalty rates. Keep records of all the hours you're working. So, send a text message to your employer saying, confirming I'm working these hours on Sunday. If you're not getting payslips, which you should be, at least you've got a documented record of the hours that you're working. So, if you do want to try to claim the wages that you're owed later you've got a really good record of the hours you worked and ideally the amount that you were paid. So, the more you can document, the better.”

From January this year, intentionally underpaying an employee’s wages or entitlements, including international students, became a criminal offence. Penalties include up to 10 years in prison and fines of more than one-and-a-half million dollars. Associate Professor Farbenblum welcomes the move.

“There are also a number of new offenses in the Migration Act and these are particularly important for people on visas and they relate to employers using a person's migration status to coerce them into accepting certain conditions at work or even in the workplace. It might be accepting living arrangements related to the workplace. But we have to do much, much more to ensure that these protections are accessible to migrant workers who are exploited everywhere in Australia. And we have to make our court systems more accessible because right now we are making some dent in some of the worst cases, but we've got a really long way to go.”

Mr Nguyen finally escaped the farm and returned to Melbourne. His parents initially paid for his studies, later Mr Nguyen took multiple jobs to finish his degree.

“It was pretty hard because I was struggling with the money at that time, I was still struggling financially. I couldn't have enough money to pay for my tuition fee. Of course my parents keep borrowing money from everywhere, but of course it wasn't enough.”

In fact, Mr Nguyen worked so hard to raise the $36,000 annual fees, he says he collapsed at university due to low blood sugar. Even so, he refused to quit.

“I was scared of making my parents disappointed because they sacrifice their life. They worked tirelessly to get me and my siblings where we are today.”

With thousands of international students signing on for three months summer holiday work, Phil Honeywood, CEO of the International Education Association of Australia, expects more reports of exploitation.

“Australia has put in place the regulatory frameworks and the appeal mechanisms to the best in class, world-class standard of employment undertaking. However, there'll always be unscrupulous players who will take advantage of young people's naivety. Really what we need young people to do is if they're signing on the dotted line to get independent advice about the contract they're signing. Ideally it would be from their education providers, job service or indeed their legal service. Make sure that if that first wage does not hit the bank account within the agreed time period, be that one week or maximum fortnight I would suggest, then clearly questions have to be asked. Make your family and your friendship group aware of where you are and how to communicate with you because often we've got mobile phone issues in rural communities. This summer is going to be really the time when the rubber's going to hit the road as to whether the architecture is correct, as to whether enough information is being provided.”

Despite speaking only three words of English when he arrived in 2012, Mr Nguyen recently finished a second masters’ degree, in advanced nursing. He is married to his childhood sweetheart with a young daughter, and is proud to have finally achieved his goal.

“This is like dream comes true. Like I've been, thanks to those hard times that I feel more mature, I feel that I can - doesn't matter what challenge, unexpected challenge or difficult times come to me, I am always ready to fight the battle.”

And he has this advice for other international students working to pay their way.

“It's important to actually know your rights, know the kind of visa you are on and don't be afraid to ask for help if you find any exploitation, any red flags.”