Listen to Australian and world news, and follow trending topics with SBS News Podcasts.

TRANSCRIPT

"Like, my mum and dad met in jail, and jail was just a bit normal growing up, and then, you know, when I started going into jail, like, I've done so many sentences it's not funny. I can't event count 'em."

That's Rocket Bretherton - a Noongar woman who grew up around drugs and domestic violence and first when to prison when she was roughly 15.

These days, she's a multi award-winning podcaster, speaker and campaigner for change - who's been working with the Justice Reform Initiative for more than three years.

Rocket says she served around 30 sentences across Queensland and the NT.

"I was all the time just waiting to get done, waiting to go back in the jail. I knew it was coming. I was dealing drugs to support my habit, and I knew that what I was doing, what I was going to get caught for, I was going to end up in jail, but I didn't really care because I sort of looked forward to going back into jail for a bit of a rest."

It wasn't easy breaking that cycle.

"I tried many times to get off the drugs when I come out of jail, but there's absolutely no support. When you come out of jail, you sort of just dumped out the doors, and if you're on a suspended sentence, you dumped at corrections ((Department of Corrective Services))."

For some people, these cycles of harm and offending can begin even younger, and in some jurisdictions, children can be sent to jail as young as 10.

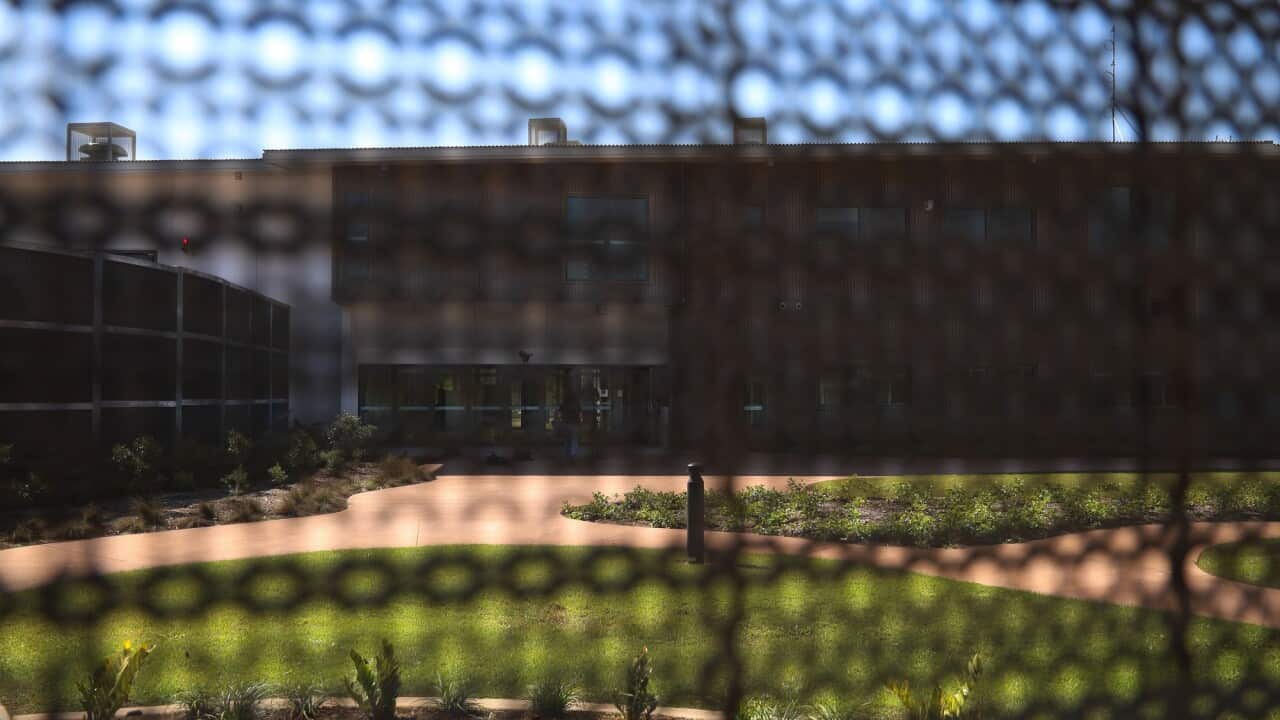

What happens when they're incarcerated will be the subject of a Senate inquiry that was established this week [[28 Oct]]...

"The ayes have it."

... through a formal motion from Greens Senator David Shoebridge.

The terms of reference will allow the inquiry to investigate whether children’s rights are being infringed, and how this sits with Australia's obligations under international law.

Allegations of abuse, the use of restraints like spithoods, and issues with overcrowding as well as the role of rehabilitation and diversion programs are likely to be a key focus.

The outgoing National Children's Commissioner Anne Hollonds says youth justice and detention systems present some of the most serious human rights issues in the country today.

"The most vulnerable children in the country. That is what we're talking about. These are children who have serious problems, mental health issues, developmental disabilities, learning problems, trauma. They're victims of harm themselves and victims of crime themselves."

Ms Hollonds handed down a major report on youth justice and detention systems in August last year.

It found state governments so-called 'tough on crime' policies are not based on evidence, and don't reduce crime.

Ms Hollonds says investment in upstream systems - like education, housing, health and child protection - are the key to driving real reductions in youth offending.

"I guess the question arises. What does it take to get action on evidence? What we've seen is that we are neglecting our responsibilities towards these children until they commit a crime and then we punish them harshly in ways that other countries are not doing, by the way."

Her report recommended the federal government intervene and establish a national taskforce, as well as a cabinet minister responsible for the welfare of children.

She also recommended enforceable national minimum standards that set out the lowest acceptable level of care - and that will be considered by the inquiry as well.

"This is a landmark inquiry that's looking at a very big problem that crosses all the federation boundaries. This is a whole of nation crisis."

A previous inquiry into youth justice has already considered Ms Hollonds' report - but it had its work cut short by the federal election.

That inquiry was chaired by Liberal Senator Paul Scarr.

"The evidence we heard was significant and deeply disturbing, and we received submissions from over 200 important stakeholders."

The inappropriate use of solitary confinement and watchhouses were key concerns, as well as the number of children in detention who were unsentenced or awaiting an initial court hearing.

"Three quarters of the children in detention are on remand, and that number has increased by approximately 10 per cent over the last few years. And within that number of approximately 800 children there is a disproportionate number of First Nations children. We're talking about 60 per cent."

Senator Shoebridge says the system is failing.

"And I don't think you could come away from hearing the data that we heard about the incarceration rates of First Nations people across the country and not think that it is a deeply racist system (that is) targeted against First Nations Young people."

Earlier this month, the Minister for Indigenous Australians, Malarndirri McCarthy, expressed her alarm at the high incarceration rates for First Nations people - particularly youth.

She told Senate estimates the government is exploring the idea of leveraging federal funding to push states and territories to meet targets under the National Closing the Gap Agreement.

Over-representation in the criminal justice is one of the 17 targets.

"And it is the frustration in terms of trying to reach out to states and territories about adhering to the agreement. There's no penalty in the agreement. And what I'm trying to do now is look at the federal funding arrangements that are made with each state and territory, over whatever the agreement might be, as to how we can input into that so that there is some kind of penalty with regards to why you're not achieving these targets."

For First Nations people like Rocket, the evidence shows that early contact with the justice system can often lead to further offending.

"You've just got to ask yourself, why are we stuck on this system that's not working. We know that the younger a person goes to jail the more likely they are to keep coming in contact with the justice system. Yeah, what we're doing at the moment is not working. We need to be looking at other stuff."

Rocket says she started to change her life when she felt valued and heard.

A program in prison allowed her to make a podcast while she was inside.

"You know a lot of people reached out to me and just said: 'Oh my God, I just can't believe the life that you've had'. And I think I always sort of grew up thinking what I had gone through as a youngster was very normal, and everyone had to go through that."

Rocket also received a visit from Arrernte lawyer Leanne Liddle while she was developing the Northern Territory's Aboriginal Justice Agreement, and she was asked to give her advice.

"I basically said it needs to sort of be like a six-month program. It needs to be an alternative to prison, and it needs to be wraparound support. You need to get help with your trauma, you need to do domestic and family violence courses. You need to be able to study - if that is what you want to study. You need to be able to get a job ready. You need to be able to work on what has caused you to offend in the first place, which might be a drug and alcohol problem. But there's also other issues below the drug and alcohol problem, you know, that led to the drug and alcohol problem."

Under its terms of reference*, the Senate inquiry has been specifically directed to seek input from people with lived experience of the youth justice system - and search for effective alternatives to the current approach.

The inquiry is receiving written submissions until December 19 - and is due to report by March next year.