"Your robot don't fight, you don't get paid," struggling robot-boxing promoter Charlie is told. So his robot fights. Welcome to the futuristic world of the new film, Real Steel. In many ways, it is quite a bit like the world we live in today - people still drive cars, watch TV, play videogames and talk on cell phones. The big difference, is, when it comes to boxing, the human is out and the robot is king. As a human boxer, the only career option left is to buy, train and fight tall humanoid robots in arenas filled with baying, intoxicated crowds.

The story follows exactly one such former boxer - the strapping Charlie (Hugh Jackman). Heavily in debt, he just doesn't have the business head it takes to run a robot-fighting business. He won't listen to advice from his girlfriend Bailey (Evangeline Lilly) - who triples up as his landlady and sexy robot technician, and whose father trained Charlie as a boxer. His luck only starts to change when he is reunited with his estranged 11-year-old son Max (Dakota Goyo), a surprisingly well-adjusted nerd (given his age and the fact that his mother just died) who combines his father's love of boxing and robots - and general daring and bravery - with a little more sense and self-belief. After a near-death experience, Max and Charlie embark on a quest to get to the top of the world of robot boxing with a most unlikely machine - an old model called Atom that they find in a robot scrapyard.

What ensues is a schmaltzy story of two flawed characters completing each other's lives and of their robot underdog prevailing over the slick, well-funded but soulless creations of the rich and glamorous. Somehow though, it doesn't get bogged down by the cheesy, well-worn plotline. That's partly because Jackman and Goyo have real chemistry and are likeable as characters. But it's mainly because the film's premise - a world where robot fighting is the norm - is novel and intriguing. I was almost grateful for the non-challenging human plot as it left my cognitive resources free to focus on the robots.

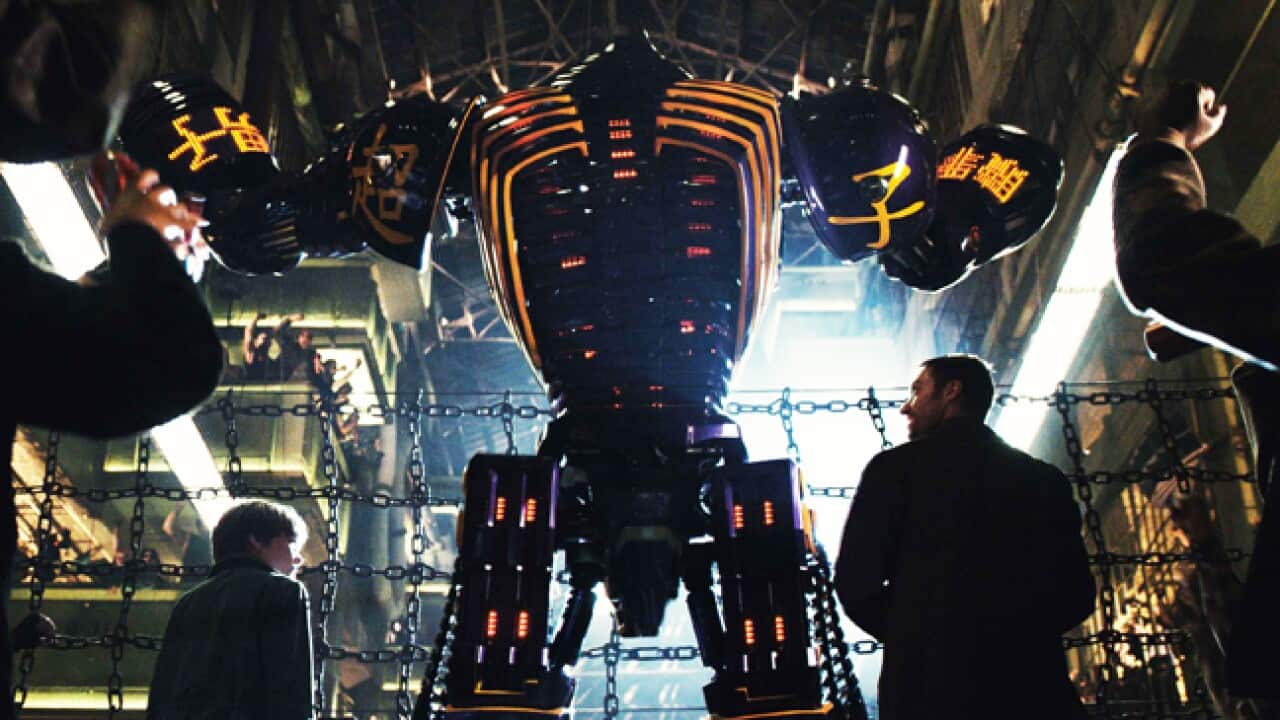

And what robots they are. Part CG, part puppetry, these lean, leaping, fighting machines (which look as if they are at least 3 metres tall) - with names like Ambush, Midas and Noisy Boy - are gorgeous, lurid and awe-inspiring in equal measure. Adorned with tattoos - one even has a neon orange Mohawk - they strut into the arena from behind curtains made of chain-mail. When "hurt", they spew purple, blood-like liquids and even writhe around. The fights are more violent than boxing yet simultaneously less upsetting as no one is actually hurt.

So, how would today's robots fare in a futuristic boxing match? One of the closest things we have today is the annual RoboGames, in San Francisco, which features boxing, sumo and kung-fu robots. Many of the robots are not humanoids - instead they have wheels and a low centre of gravity, giving greater stability, but the contest does feature humanoid boxers, too. Simone Davalos, the Robogames co-organiser, describes these humanoids as "amazing, beautiful, intricate" but says they bear little resemblance to the powerful machines in the film, who survive massive blows to the head. "Real Steel is a long way off," she says. "At present the robots average 18 inches high and they tend to be unstable."

Instead, she says the most realistic thing about the film is the audience, which is similar to the one at the RoboGames: "A heaving morass of seething humanity of all ages and stations, frantically screaming for, essentially, really loud and exciting applied physics and engineering."

Robot stability is an area of active research - and not just because of the demands of boxing. Chris Atkeson and Ben Stephens at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania work on making humanoid robots that are stable when struck. Domestic robots with this capability could survive bumping into other passengers on the bus or babysit children who might tackle them without falling and harming the children, explains Atkeson.

Earlier this year, the pair got volunteers to try to push over an adult human sized humanoid, the Sarcos humanoid robot (watch video here). Atkeson says the robots could handle a force of 40 newton-seconds without falling ever, similar to the force applied by a professional human boxer (PDF), although to survive a boxing match, a robot would also need the ability to predict what the opponent will do next.

In the film, the key to the eventual success of Atom, Max's rehabilitated "junkyard dog" of a robot, is a "shadow" function that has, for some reason, been abandoned in more modern boxing robots. When in shadow mode, Atom is able to copy the motions of his human owner. The moves can be saved and then re-deployed in a boxing match - to great effect when his human teacher is Charlie (formerly one of the best human boxers the world had ever seen).

Atom's shadow function could be achieved by teaming up a sophisticated camera with computer vision algorithms to process the human actions. AI could then be used to map those actions on to his own body and copy them.

Rather like stability, such learning from demonstration (LfD), is a skill many real-life roboticists would like their creations to have, says Sonia Chernova of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts. It would allow a robot to be easily taught how to operate a new piece of machinery, or fold your clothes just the way you want, say. "It is highly unlikely that engineers at a factory will be able to predict and pre-program every useful capability a priori," she says. "Users need the ability to expand the capabilities of the robot by teaching it."

The Microsoft Kinect sensor, an add-on for the Xbox 360 games console, uses a 3D camera to transpose players' movements onto animated video games characters. It has been a boon to LfD because it can also be used to map movements onto robots. One of Chernova's students has used the technology to teach a small humanoid robot - the Nao - to move by demonstration, as the website version of this story shows in the video above.

The biggest obstacle is that robots do not have the same joints as humans, so they can't make the same movements. "All the key components are there," says Chernova. "The speed and precision required to teach boxing in this way is not."

Before the film began, I wasn't sure what I would make of Real Steel: I love robots and films about robots (in July I was a judge at the first robot film festival in New York) but I am squeamish about human boxing. As it turned out, this was the perfect combination for me.

These machines aren't the destructive, autonomous bots of the Terminator films, nor are they creepy copies of humans common in other sci-fi. Instead, apart from a couple of instances where it seems that the audience is supposed to think there is some kind of spirit or soul inside of Atom (can he "understand" Max?), which are easy to ignore because this nonsense isn't really followed through, the film portrays a much more realistic vision of how humans and robots might one day live together.

The robots are doing something that they are good at (better than humans) and that is entertaining and inspiring, without having to take on qualities or features that are freakish. What's more it takes the place of humans from doing something that is violent themselves. Bring on the robot boxer - I might even start watching boxing then. And as Heather Knight, the brain behind the robot film festival and a roboticist at CMU, says: "Why stop at boxing? It would be great if we could have robot gladiators instead of human warfare."