As seafood sales soar around the festive period and in the lead-up to Australia Day, consumers may wonder if they always get what they pay for?

Food fraud is a rapidly growing problem worldwide, according to experts.

"The act of purposely selling fake, mislabelled or substituted food for economic gain is food fraud, and it is a global multibillion-dollar problem," Food Fraud Advisors principal consultant Karen Constable said.

"We have increasingly complex supply chains and ways of buying and selling big bulk commodities."

"So globally, the industry actually thinks that food fraud is getting bigger and worse."

A 2021 AgriFutures Australia report estimated Australian food fraud losses at up to $3 billion annually. High-risk sectors include seafood, wine, and honey.

Globally, food fraud is estimated to cost up to $73 billion annually, according to Australian government figures.

Additionally, the health risks are huge. According to NSW Food Authority, there are around 4.68 million cases of food poisoning each year nationwide.

That has motivated a diverse group — including Sydney Fish Market — to work with nuclear scientists to determine exactly where our food is from.

In a lab south of Sydney, a dedicated team of scientists is making progress on a solution to this growing food fraud problem.

The research is led by Bangladeshi-born Dr Debashish Mazumder, who holds a Master of Science from Imperial College London and a PhD from Australian Catholic University.

For the past decade, he has worked to verify food origins at the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO).

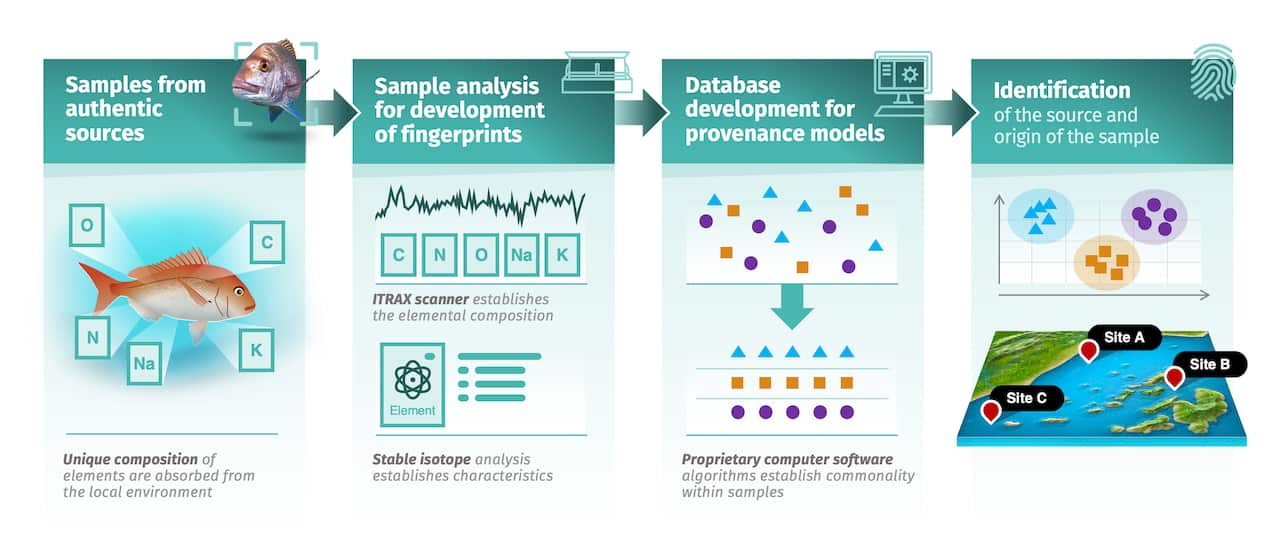

"The technology we have developed analyses the environmental 'fingerprint' of a food," he said.

"We decode this environmental fingerprint through a machine learning algorithm which can, with a high degree of accuracy, confirm a sample's source or origin."

ANSTO's powerful tool can help determine the provenance or origin of seafood, other animals, and plants.

The system uses stable isotopes, X-ray fluorescence scanning, and customised computational modelling. Scientists can also draw on ion beam analysis and neutron activation analysis.

With this technology, Mazumder can place a thin slice of a frozen snapper onto a tray, and moments later, data appears on a laptop screen.

The numbers reveal a specific combination of trace elements like copper and calcium. This is then matched against data from a specific site, such as an ocean or estuarine fishing ground.

In this way, scientists identify where the fish bred, fed and grew.

"So far we have analysed 59 different species of seafood, which is a huge resource for Australia," Mazumder said.

"And overall, we have achieved around 85 per cent accuracy."

A portable X-ray fluorescence scanner adapted from the mining industry can also be deployed to external sites.

The project, funded by the federal Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry through its National Agriculture Traceability Grants Program aims to help Australian business and industry to better tackle food fraud.

With this sophisticated equipment, scientists can determine if a fish — like barramundi — was line-caught in the Northern Territory or farmed in Asia.

"Food fraud is basically tricking a customer about the source and the quality, for making money," Mazumder said.

"So, this technology ensures that the label is correct."

Australian seafood is generally considered high-quality, safe to eat and at low risk of contamination — due to stringent regulations, effective management regimes, and generally clean, unpolluted marine environments.

"Our fisheries management is regarded as one of the best in the world. So that is why we have a great reputation for high-quality premium seafood," Mazumder said.

Australia's seafood industry is valued at up to $4 billion annually and employs more than 17,000 people.

However, the country also imports around 60 per cent of all the seafood consumed.

And that’s where the fraud risk multiplies.

"As Australians, when we think about buying premium Australian seafood, we really want to know that we are getting what we paid for," she said.

"But there remains a risk that cheaper seafood from overseas can be substituted for Australian-grown."

From July this year, new laws will require Australian hospitality businesses — such as restaurants and cafes — to label seafood dishes as Australian-grown, imported or mixed. Failure to comply could result in fines.

But the problem goes both ways.

Food sold overseas as Australian-grown and fetching premium prices may in fact also be mislabelled.

"Foods sold offshore such as cherries, lamb or prawns that are labelled Australian, may not be," said Constable.

"And it is very hard to prosecute food fraudsters without some technology to back you up."

Jes Sammut leads the aquaculture research group at the University of New South Wales and works with the ANSTO team. He said industry supports technology to better identify food origins.

"Seafood for instance, has very long supply chains from where it's produced right through to the retail sector," he said.

"And all along those supply chains, there are different participants who may be involved in fraud, or fraudulent activities.

"So, it's critically important that we have technology that can verify where something has come from and how it was produced, whether it was wild caught or farmed."

Globally, contaminated food causes 600 million illnesses and 420,000 deaths each year, the World Health Organisation reports.

Mazumder said contamination remains a serious problem in Australia, too.

"Contamination could be bacterial or viral, or with metals like mercury, lead or other toxins," Mazumder said.

"In fact, contaminated food impacts people every day in Australia, and billions of dollars are spent on public safety in relation to food," he said.

As part of its new food provenance project, ANSTO is collaborating with scientists offshore to build a vast database of foods and harvesting sites.

"We are creating a database of many food products from all over Australia, and now Southeast Asian countries are with us," said ANSTO science program leader Patricia Gadd.

"And this database has a robust number of samples and of different types of food products as well."

Food products include export items like mangoes, rice and turmeric.

Australia's native Kakadu plum — also called the gubinge — is very high in vitamin C and is among foods vulnerable to substitution.

"We purchased packets of Kakadu plum powder from nine different online suppliers, and all of them were based overseas," said Mazumder.

"And when we tested them, all the samples were fake, and we did not find one genuine Kakadu plum powder."

Mazumder has devoted more than a decade to this work. He hopes it will eventually reduce food fraud and help to save lives, worldwide.

"One day, consumers might be able to use this technology on a mobile phone to scan the barcode [of a product] and see its elemental composition, which is related to a particular the environment, and confirm the product they are buying coming from an authentic source," he said.

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.

Sharing business secrets of inspiring entrepreneurs & tips on starting up in Australia's diverse small business sector. Read more about Small Business Secrets

Have a story or comment? Contact Us