The Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Sector (ACCHOS) has been widely lauded for its success with managing the spread of COVID-19 in Indigenous communities - its approach has even been said to be ‘leading the way’ in how to deal with the virus.

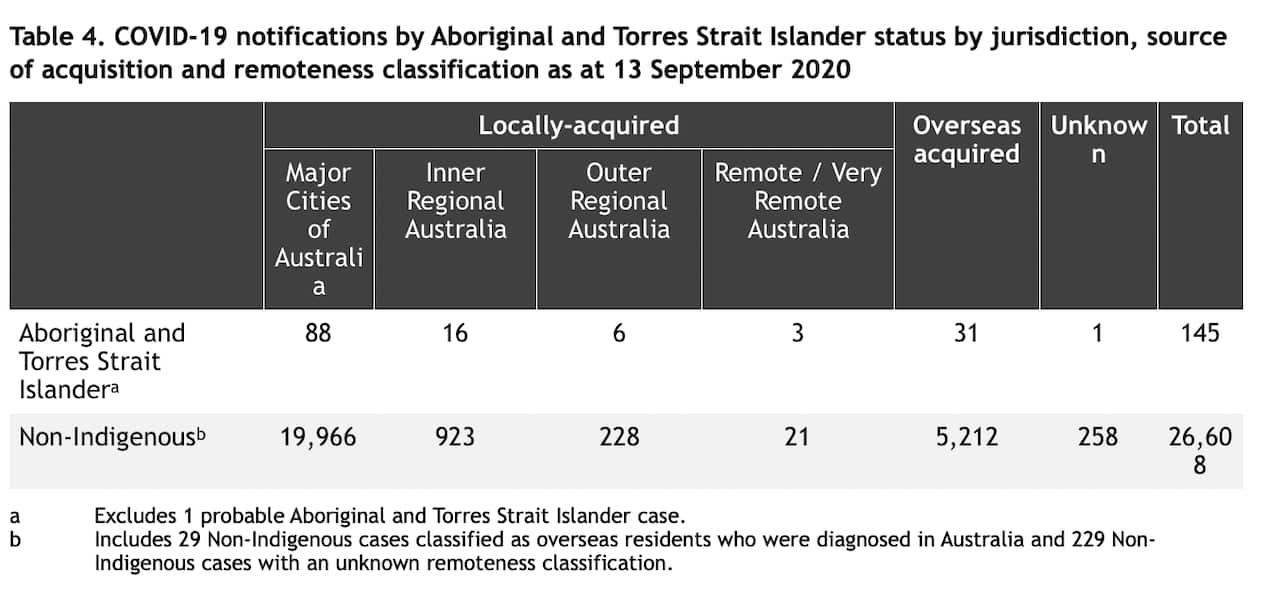

Out of 28,000 COVID cases recorded in Australia, as of September only 145 of those were Indigenous Australians - or 0.005%.

Multiple leaders in the sector have cited autonomy and the connection its services have with their local communities as one of the key reasons for its success. But they also acted fast - in many cases, ahead of the federal government, and used common-sense and effective approaches involving face-to-face contact and bringing rapid testing into remote areas to prevent, rather than patch pandemic issues.

But it perhaps hasn’t received as much coverage as other health initiatives. “The quality level of leadership, expertise, and reach achieved by ACCHOS is not widely recognised across mainstream Australia,” said Vicki O’Donnell, a Nyikina Mangala Aboriginal woman from Derby, and the CEO of the Kimberley Medical Services.

There is a clear gap in life expectancy and broad health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians - and fears were justified that this community could be severely impacted.

It’s a fear that’s been realised in the US. Native Americans have the highest infection rates in the country and are only second to African-Americans and Hispanic-Americans in terms of COVID-19 related deaths.

The Indian Health Service (IHS) - unlike ACCHOS in Australia - is an agency within the US Department of Health and Human Services.

The IHS treats over 2.2 million Native Americans with members from over 560 tribes. It’s been described as being underfunded and invisible in terms of the overall health system in the US.

While in Canada, Indigenous communities have had similar success in dealing with COVID-19 to First Nations people in Australia. The rate of COVID-19 infections within Canada’s Indigenous people is less than a quarter of non-Indigenous Canadians.

And they also took an autonomous and community-led service approach.

For Olga Havnen, the CEO of the Danila Dilba, this has been crucial.

“That notion of self-control, self-determination, local control, local knowledge, local networks, and relationships [are] absolutely vitally important,” she said.

“If I had to seek permission through some sort of government agency and department I reckon I'd still be waiting.”

And as a result, not many cases have been recorded: 88 cases have been diagnosed in capital cities, 16 in inner regional areas, six in outer regional Australia and just three in remote communities.

How did the Aboriginal health sector respond to the pandemic?

Danila Dilba is an Aboriginal medical service based in Darwin, and their pandemic response was managed by Havnen.

The language of the health messages was absolutely key.

"So even this thing of talking about viruses or germs doesn't make sense to a lot of Aboriginal people because they don't necessarily subscribe to germ theory," she said.

Instead, Havnen framed the messages with terms like “illness or sickness” to ensure the message would be understandable. This focus on language is in contrast to to experiences in other communities, with Victoria’s health agencies forced to address translation issues in communicating crucial COVID messages.

But Danila Dilba's work didn't stop there. They provided care packs and drew on their mobile outreach to Aboriginal communities in Darwin. Misinformation has been rampant in every community -- but in using this, Danila Dilba was able to address this directly.

"Some Aboriginal people would say, 'Oh, well, you know, that's a disease or an illness sickness that comes from overseas, it belongs to white fellas, this isn't going to affect us','" she said.

"Other people believed that the sunlight or exposure to sunlight would kill whatever the disease is."

Havnen says the fight against misinformation isn't over, and she isn't prepared to rest on Danila Dilba's success so far.

Havnen also believes the swift action by ACCHO's around Australia was borne out of the response to the devastating flu outbreak that impacted APY Lands a few years ago.

"The deaths rate there, as I understand was sort of six times higher than the normal population," she told The Feed.

That flu outbreak only affected a small number of people but the impact wasn't lost on Havnen, and others within the Aboriginal health sector.

She says the impact of highly infectious diseases doesn't only disproportionately affect Indigenous communities because of their poor health outcomes but also because often communities live in crowded living conditions.

That's why Havnen's health service in Darwin took immediate action. Danila Dilba is in contact with 80 per cent of Darwin's Indigenous population, and was able to distribute public health messages before both the NT and federal governments.

The Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Service

For the Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Service, acting fast and with clarity was a high priority.

The chief operations officer Rob McPhee told The Feed its medical service sent out language-specific health messages before those developed by the federal government in English.

"As restrictions were introduced, we partnered with Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Culture Centre and West Australian Aboriginal Translation to continue providing up to date information for the community in Kimberley Kriol and other Kimberley languages," McPhee said.

The medical service credits its success in large part to the "powerful connection" it has with the Kimberely Aboriginal community.

But Dr Lorraine Anderson, a Palawa woman from north-western Tasmania, who worked on this response says its success has not been without its challenges.

In the first few months of the pandemic, testing logistics in remote Aboriginal communities were extremely difficult. If there was a suspected case, the person would need transport to regional centres for testing and had to quarantine away from their community while they waited for results.

But in May, the Kimberely Aboriginal Medical Service increased remote clinics and conducted Point of Care COVID-19 testing on GeneXpert machines.

"This testing became available in Kununurra, Halls Creek, Derby and Broome and also at remote Aboriginal communities of Bidyadanga, Balgo, Beagle Bay and Billiluna," Dr Anderson told The Feed.

And Balgo became the first remote Aboriginal community in Australia to undertake testing for COVID-19 on a GeneXpert machine.

Tharawal Aboriginal Medical Services

The most recent Census in 2016 found that Sydney is among the largest and fastest-growing areas for First Nations communities in the country with one in nine Indigenous Australians residing in the city.

It’s why Sydney based Tharawal Aboriginal Medical Services took action as soon as it was clear how dangerous the virus was, and it impacts on vulnerable groups like the elderly. It came to the decision to isolate over 100 elders in their community for just over three weeks.

“Our main interest was shown with our elders because we treat our elders like gold because they are ones that carry all information in terms of cultural issues, so we keep them close to our chest,” told CEO Darryl Wright The Feed.

Wright, a Dhanggati man, says keeping in communication with the elders isolating was paramount. The organisation kept in contact through text messages, Facebook, and Zoom exercise classes.

Tharawal organised deliveries of food, medicines, and other essential supplies, as well as doctor visits and regular check-ups for the elders within the community.

Tharawal also cultivated relationships with Woolworths and the local pharmacy to ensure it was able to get all the essential products to the elders isolating.

The medical service organisation also had a relationship with the Reiby Juvenile Justice Centre, they provided over 500 meals to Tharawal a week to deliver to elders in isolation.

Wright says they also set-up a drive-through at the centres’ car park for those who wanted to get out of the house for their medical check-up.

Healthcare workers would meet clients outside for approximately ten minutes to administer any kind of medicine they needed or check-up on their well-being.

Tharawal organised a pop-up testing clinic that ran for a month and tested 1500 people without any positive cases. The clinic was closed towards the end of September, as the numbers in NSW continued to decrease.

“There was one sort of sickness but it had nothing to do with the virus. So that was really worthwhile,” Wright said.

Uncle Ivan Wellington was among the elders in the community who were isolated, he says, he never felt alone because of the support of Tharawal.

He’s been friends with Wright for just over twenty years.

“I needed that support. Because I knew that I couldn't go out into the community while the sickness, the pandemic was there and they gave me that,” Uncle Ivan told The Feed.

“Tharawal came to my door, they came to my window."

Through award winning storytelling, The Feed continues to break new ground with its compelling mix of current affairs, comedy, profiles and investigations. See Different. Know Better. Laugh Harder. Read more about The Feed

Have a story or comment? Contact Us