Warning: This story may cause distress to members of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island communities and contains images of deceased persons.

Watch The Feed’s full documentary on YouTube.

A young man with a face covering and paint on his hands greets us in some bushland. We’re a 30-minute drive outside Melbourne and we’ve followed their directions to get here.

He gives us the pseudonym Chris and says he will escort us the rest of the way to meet the group.

After previously exchanging encrypted messages, this group has agreed to be interviewed on the condition they can obscure their faces and pick the location.

For a year-and-a-half, this anonymous group from Melbourne has been going after colonial statues – toppling, breaking or defacing them in the night. While there has been more than one group going after these statues, this one is the most active.

Attacks on Australia’s colonial statues often ignite intense debate. Are these colonial figures the people we should commemorate in our cities and towns, or is it time to check in on their legacies?

But this group is done asking questions. They say they see the issue clearly and are taking it into their own hands. They've come together to tear down and vandalise colonial statues.

We wade through long grass and reach an abandoned building in a park. Chris says the group spent the day preparing the space for our interview. Around us are messages, much like the tags they leave after they’ve targeted a statue. Now the paint on Chris's hands makes more sense.

Five members show up, and some take on the job of lookout during the interview.

They say it’s hard for them to be on camera, but they want to show that they’re "just really normal people that have decided to stay up late and go do something", one member, who goes by the name Lewis, tells us.

Knowing their actions are illegal, they do everything they can to avoid being caught, which they say would slow them down. But they believe in their mission and have been ramping up their actions since last year.

Disguises, motivations and a ‘list of priorities’

Dressed in all black, with socks over their shoes to cover their footprints, gloves on their hands and face coverings, they say it doesn't take too long to topple a statue, but it takes some planning.

“There's a list of priorities. Topple is obviously number one and then decap, number two, and graffiti number three," a member, who goes by Liam, says.

Reflecting on their toppling of the Captain Cook statue in Melbourne’s St Kilda last February, which made international headlines after a video was shared online, they said a small team assembled to take it down.

“We had another few people rigging so that as the statue started to fall, it would fall in a very specific way and not endanger the people cutting,” another, who goes by the name Nathan, said.

There's a list of priorities. Topple is obviously number one and then decap, number two, and graffiti number three.Liam, member of the group

“Much like felling a tree, really.”

Around days like the King's Birthday and Australia Day, when tension is heightened around how we remember our history, this group goes after statues of Australia’s colonial figures.

They say these statues spotlight a violent colonial system and all should be removed.

"They tell the history of white discovery, or I guess the history of white supremacy. And in some ways, by taking them down, it also tells the history of resistance," Lewis said.

None of the members are Indigenous but they say they have some community support. They have also received criticism from members of the Indigenous community.

The actions of this group – and others like them – have been strongly condemned over the years.

Back in 2017, former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull told 3AW radio in Melbourne that taking colonial statues down would be "Stalinist". Former prime minister Scott Morrison told Sydney radio station 2GB in 2020 the negative parts of our history are "not a licence for people to just go nuts on this stuff".

Others have called the people doing these actions “extremists”.

Toppling and trashing Australia’s most well-known colonial figures

The group doesn’t say how many times they’ve targeted a statue but say they’ve cut down the statue of Queen Victoria in Geelong. They say they've pushed down a monument to John Batman, who is often called Melbourne’s founder and was involved in inciting attacks against Aboriginal people during the frontier wars. Both monuments haven’t yet been reinstated.

They also decapitated the 73-year-old statue of King George V in Melbourne's Kings Domain, on the King's Birthday public holiday last year.

The statue is still standing without a head - because they've taken it.

"Pretty ugly king," Chris jokes as he pulls the bronze head out of a bin, where it’s been hidden during our interview.

"We feel that it's important that this king no longer has a head," Liam said.

"But we by no means take it lightly, and it is a serious piece of evidence."

Two weeks after the interview, the head resurfaced at a Melbourne concert for the group Kneecap, a trio from Northern Ireland known for its anti-colonial rap. After the show, the band posted a photo with the words: “Remember, every colony can fall.”

An ‘imbalance’ in our landscape

It’s hard to know how many colonial monuments and statues are in Australia as there’s no central register. But one volunteer-run site, Monument Australia, which operated until 2023, crowdsourced information on Australia’s monuments. By its count, there are hundreds.

Some of the most controversial statues are in Hyde Park in Sydney's CBD. There is a bronze Captain Cook statue from 1879 with the inscription “discovered this territory", which stands despite Indigenous Australians being the world's oldest continuous living culture.

In the same park, Governor Lachlan Macquarie, who helped establish Australia’s first bank, is described as a “perfect gentleman”. What it fails to mention is that as described in his journals from the time, Macquarie incited a campaign of “terror” against “hostile natives.” He ordered for the bodies of those who didn't submit to colonial rule to be hanged in trees as a warning to others.

The City of Sydney Council agreed in 2023 to take another look at the plaques of 25 colonial statues after its first Aboriginal councillor, Yvonne Weldon, said it was time to check in on how we told our history.

“Walking around Sydney, you’d be forgiven for thinking that no one was here before the British arrived," Weldon told The Feed in a statement.

"Sadly, the erasure of First Nations history, culture and perspectives is reflected in the public domain. There is not a single publicly funded statue commemorating a First Nations person in the City of Sydney. This imbalance in representation is unacceptable.”

Walking around Sydney, you’d be forgiven for thinking that no one was here before the British arrived.Yvonne Weldon, City of Sydney Councillor

Rather than pulling down statues, Weldon says she wants balance and truth-telling, acknowledging that consultation would be required in the process. But progress has stalled, she says.

“Council unanimously adopted my motion 18 months ago. It’s disappointing that little progress has been made,” she said.

Mounting attacks on Australia’s colonial statues

There is a growing trend in Australia of vandalising and cutting down these statues, says Richard Silink, a director at the International Conservation Service – one of just a few places in Australia that repairs these statues.

In response, one small group, The British Australia Community, is lobbying state and local governments to do more to protect these statues. Its president, in online statements, said there is too much “Anglophobia” in this country and not enough pride around the “contributions” of the British.

Statues have been targeted internationally too and yielded different results.

In the UK, footage of the statue of slave trader Edward Colston went viral during the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement. An impassioned crowd in Bristol publicly toppled his statue and rolled it into the city's harbour. After these scenes, almost 70 tributes to slave traders and colonialists in the UK were taken down or removed, according to The Guardian.

In the US, about 100 confederate monuments on public land came down in the same year, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. Over 700 monuments, commemorating an era when white southerners in the US violently sought to maintain white supremacy and slavery remain in the country.

The monuments that councils wanted removed

There are only two colonial monuments in Australia that councils have voted to remove or keep down.

A Captain Cook memorial in Melbourne – which was not on display at the time of last Tuesday’s vote after receiving significant damage – will not be returned, the City of Yarra decided, saying that it would cost $15,000 to repair. The memorial had been frequently targeted in recent years, according to the council meeting.

The anonymous group we spoke to did not list this as one of the places they targeted.

Victoria Premier Jacinta Allan said at a press conference on Wednesday morning: “

And we’ve got an alternative here that’s a win-win for everybody.”

We haven’t got the money to be the protector of every statue.Victoria Premier Jacinta Allan

Mayor Stephen Jolly said the Captain Cook appreciation society had come in “like a knight in shining armour” asking to take ownership of the monument’s plaques.

Jolly told council that it had to look at it as a “boring economic issue”, rather than a debate about whether it was appropriate.

Hobart divided over William Crowther statue

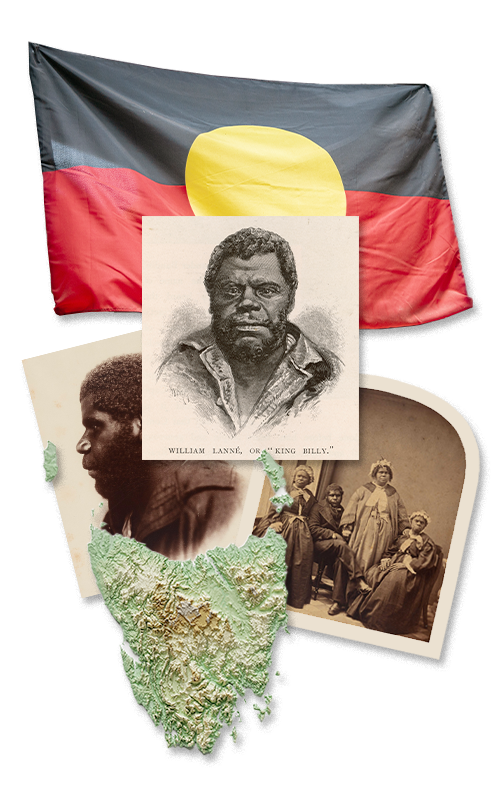

The statue of former Tasmanian premier William Crowther was voted by Hobart City council to be removed in 2022 after years of campaigning from the Tasmanian Aboriginal community. Crowther, a doctor-turned-premier, is accused of breaking into a morgue and stealing the skull of whaler and Aboriginal man William Lanne in 1869.

Although the majority of councillors voted to pull the statue down, councillor Louise Elliot led the charge to keep it up.

“I personally think the decision to remove the statue is disgusting. I think it's the ultimate virtue signalling act. This came off the back of the Black Lives Matter (movement) in the US where there were statues of people that had huge involvement in slavery,” Elliot told The Feed.

“Dr Crowther's story is nowhere near comparable to that.”

A number of historians, based on public records and witness reports made during an inquiry from the time believe that Crowther was behind the decapitation and theft.

Elliot says even if Crowther were guilty of stealing William Lanne’s head after he had died, she believes it would be inappropriate to apply modern standards to colonial figures.

“At the time, there was a competition for bones of Aboriginal people, which of course is outrageous to us and would not be anywhere near acceptable now.

“But at the time, it was normalised behaviour.”

Before the council could lawfully remove the statue, vandals chopped the statue off at the feet and spray painted the words “WHAT GOES AROUND".

No one has ever been arrested or charged for it and the anonymous group who The Feed spoke with deny involvement in this act.

Elliot says actions of this nature are “arrogant”.

“They believe they're heroes and that they're doing almighty great things and changing the world,” Elliot said.

‘Not a time to celebrate’

There are mixed opinions within Indigenous communities across Australia on how to deal with these statues, monuments and dedications to the colonial era.

Imogen Johnstone, a Kamilaroi woman, wants them to come down and stay down. She says it’s not a time in our history that should be celebrated or glorified in public spaces.

“I know for myself it represents death and the genocide of my ancestors,” Johnstone said.

She says this reluctance to pull down colonial statues wouldn’t be accepted for any other Australian figure accused of violent crimes.

“When they come down, there is a little bit of relief and also praise that someone's done it,” she said.

But she says it’s not as simple as just taking a statue down.

“On the other hand, [the people behind it] don't understand the consequences that it holds on Indigenous and First Nations people.”

After the King’s head was removed in Melbourne, Johnstone, who lives close by, was accused by a former friend of vandalising the statue.

“It actually causes a big issue of racism, and we're instantly made to be the stereotype of like a loud, violent, angry Aboriginal (person).”

Johnstone says unless the broader public is told why these statues should come down, people will continue to resist change and won’t learn what happened during colonialism.

Statue reprisals and simmering tensions

Indigenous monuments and statues have also been vandalised over the years.

In May last year, a public Aboriginal sculpture on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula was defaced with the words: “YOU TRASHED OUR STATUES SO WE TRASHED YOURS.”

When we asked the group about the criticism of their actions in the First Nations community and claims that their actions stoked more division, the members fractured.

Lewis said: “I think racism in this country has been here from day dot and maybe something like the toppling of a statue, maybe it flares it up, but maybe it's just exposing what's always around us.”

But Lewis said they were unsettled by the reaction.

“Maybe something we need to think more about or have more conversations about.”

Nathan stood firm and said he wouldn’t pin the division to the toppling of a statue.

“I would attribute that to so many leaders who are just trying to exacerbate political polarisation and othering within our communities,” he said.

Despite the backlash and ongoing investigation by police, Nathan says they plan to ramp up their efforts.

“At the end of the day, if you're the white Australian and you're angered by a statue coming down, take a good hard look at the fact that Aboriginal people have seen genocide, dispossession, endless violence perpetuated against them,” he said.

“If we don't escalate in some regard, it'll be business as normal.”

For 300+ bold and provocative titles, head to SBS On Demand’s We Go There hub.

Through award winning storytelling, The Feed continues to break new ground with its compelling mix of current affairs, comedy, profiles and investigations. See Different. Know Better. Laugh Harder. Read more about The Feed

Have a story or comment? Contact Us