Watch The Feed's Short Documentary on Australia's Trophy Hunters

This article contains images of animals that may upset readers.

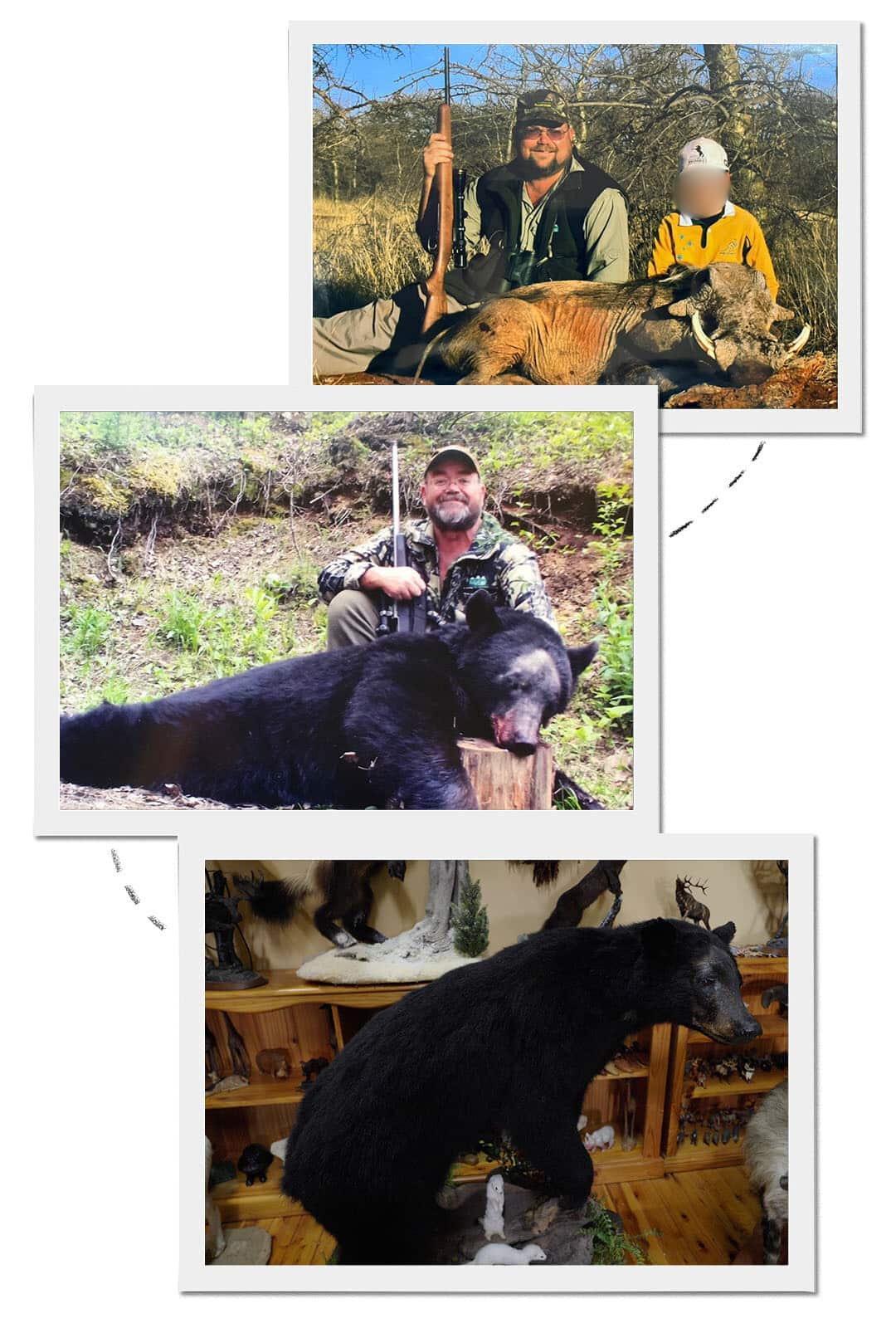

In a trophy room just outside Goulburn in regional NSW, glassy eyes watch from every direction. Antlers stretch toward the ceiling and the air smells of chemicals used to preserve dead things and the dust that inevitably settles over years of collecting.

Floor to ceiling, the walls are covered in taxidermy: some heads, some full bodies. Couches have skins thrown over them and coffee tables are decked with tusks.

Darren Plumb gestures toward mounted animals and says that almost everything in the room, he’s hunted.

Mountain zebras from South Africa, black bear from Canada, brown hyena from Namibia, Himalayan tahr, jackal, steenbok, oryx, kudu,and caracal.

"In excess of ninety," he says. Plumb, who is now a board member in NSW for the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party, has been hunting since he was five. Soon he’ll be 60.

"Some people run a marathon to get a medal," he says.

These are what he refers to as his medals — markers of achievement for someone who grew up in a small town of about 2,700 people, and went on to see rural corners of the world many travellers never reach.

"It can be said that it's hours of nothing and then 30 seconds of a total adrenaline rush," Plumb says.

"It's the camaraderie. It's not actually the killing of an animal, it's the getting out there, just trying to see if you could outwit an animal on their terms."

When asked how much he’s spent, he laughs. "I tried to add that up one night and stopped. It was just phenomenal."

At least $100,000, he offers.

He points out some of the more recognisable animals in the room.

"Warthog," he says, gesturing. "They’re cute because they’re ugly."

He says Disney has stacked the deck of public sympathy, turning some animals into familiar, likeable characters and leaving others without that glow.

For hunters, he says, that means the public respond with emotion, not context.

The fight over Australia’s hunting trophies

For years, Australians have boarded flights bound for Africa, North America and beyond to hunt giraffes, zebras, black bears, polar bears and more, and bring their remains home.

They call them trophies, but even among hunters, that word can feel uncomfortable.

At the federal election last May, the animal welfare organisation Humane World for Animals (HWFA), helped secure political support for a wider ban on trophy-hunting imports. Several independents, including David Pocock, as well as the Greens and the Labor Party, signalled they were in favour.

In a statement to The Feed, the federal government said: "The Albanese Government supports this initiative, with work being undertaken by the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water to progress it."

The proposed ban, if accepted as is, would be Australia’s toughest crackdown yet, blocking the 20 most popular hunting trophies from entering the country in a bid to deter people from travelling to hunt them.

Over the past decade, Australians have imported — or applied to import — more than 1,000 hunting trophies from 46 different mammal species protected under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), including 299 American black bears, 147 Hartmann’s mountain zebras, 47 hippos, 17 polar bears and 16 giraffes.

On the list are many of the animals that line Darren Plumb’s walls.

Some, like the red lechwe, a species of antelope, are recognised as near threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Others, like the American black bear — Australia’s number one imported hunting trophy — are classified as least concern, with growing populations.

Nicola Beynon, head of campaigns for HWFA, has been one of the leading voices behind the push for change.

"Trophy hunting has no social licence in this century. It's a practice that I think most people wish was left behind in the last century," she says.

While US hunters import the majority of global trophies, Australia is among the top 10 trophy-importing nations in the world, according to HWFA estimates.

In 2024, Botswana’s then President Mokgweetsi Masisi hit back at Germany after officials proposed tighter restrictions on elephant trophy imports, offering to send 20,000 elephants to Germany and asking how Germany could have an opinion when Botswana had rebounded elephant numbers to the largest population in the world.

Namibia’s former environment and tourism minister, Pohamba Shifeta, has similarly warned that blanket import bans could harm conservation and rural livelihoods, arguing that without alternatives to replace hunting revenue, "both our people and wildlife will suffer".

But despite pushback, Beynon says Australia has a right to back a prohibition.

"We've already prohibited the trophies of elephants, lions and rhinos, and there's all sorts of contrabands that we say we don't want in this country."

Putting a price on a head

Hunters such as Plumb see it differently. They argue that if people understood how the system actually works, the reaction might be less visceral.

"The keyboard warriors," he says, "have most likely never set foot in the countries where those animals are taken".

"If you take Africa, for example, the local communities look after their animals because they know there’s going to be someone like me that’s going to come over and shoot a zebra," he said. "I’m going to pay $1,000 to shoot that zebra."

To Plumb, the logic is simple: giving wildlife an economic value creates an incentive to protect it. He describes it as a cycle that feeds both community and funds conservation — and it's the common argument made by hunters.

He says trophy hunters only target old, solitary animals.

"So you're really looking for an older animal," Plumb says. "They either die of old age or, in my case, hopefully I shoot them, I do the taxidermy and put them on the wall and then I can look at them for the rest of my life."

He says meat rarely goes to waste, and hunts are regulated with government-issued permits.

"Meat and protein goes back to the communities," he says. "In Africa it’s all used. In North America and Canada, the meat by law has to be taken and used, it can’t be left on the mountain."

'Interfering with natural selection'

Nicola Beynon says that in practice, the idea that only specific animals are targeted is a fallacy.

"Hunters are going for the animals that have some of the most impressive physical traits," she says.

"You’re removing the strongest, healthiest animals, weakening the gene pool and the resilience of their populations … you’re interfering with survival of the fittest."

She also questions how hunts are carried out.

"These are tourists, they're not always skilled hunters," Beynon says.

"They can use hunting weapons that are cruel, like bows and arrows, which aren’t very good at getting a quick kill."

The exception, not the rule

In a reserve near Cape Town, South African freelance journalist Adam Cruise watches giraffes wander past, unbothered by the sound of a nearby vehicle.

Cruise broke the story of Cecil the lion — the research-tagged animal killed in 2015 after being lured out of Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe.

The well-known male lion was killed by an American trophy hunter. Zimbabwean authorities said the lion had been shot with a bow and arrow and then tracked for hours before being killed with a rifle.

The global backlash helped trigger Australia’s move to restrict lion trophy imports.

"It was really nice to see those giraffe just ambling slowly past and not being skittish. On a trophy hunting ranch you would see they would run away straight away at the sound of a vehicle," he says.

Cruise has spent years examining the claims made by hunters and industry bodies and says the argument that trophy hunting benefits local communities frustrates him.

He calls it patronising and a convenient excuse to hunt.

He points to the practice of distributing meat, particularly elephant meat, to communities already dealing with human–wildlife conflict and describes it as an insult.

"I mean, it's like it's, you're in a zoo and the zookeeper comes along and tosses a piece of meat into your cage. That doesn't help people at all. It doesn't stave off hunger because it's once in a while."

"In 50 years of trophy hunting, these communities remain as poor as ever."

In 50 years of trophy hunting, these communities remain as poor as ever.Adam Cruise, Freelance Journalist

Follow the money

Independent research, including peer-reviewed studies in major conservation journals, shows that in many African countries, only a small share of trophy-hunting revenue reaches the communities living alongside wildlife.

Studies by Economists at Large and research published in journals including Biological Conservation tell a similar story: in many places, much of the money leaks out to foreign-owned operators, quotas are weakly managed, and the benefits end up concentrated among a small local elite — meaning many communities see little direct gain.

"Most of that money is going back to the trophy hunting company, which is also often foreign-owned. When they are employing locals, they're employing very few of them and on very low wages," Beynon says.

But there are exceptions hunters often point to — and researchers agree they’re real, just not the norm.

Namibia: A rare success story

Namibia’s community conservancy model is widely cited as the most successful version of trophy hunting in Africa.

There, communities co-manage land and receive guaranteed revenue-sharing from hunts. A study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America shows this model has supported anti-poaching patrols, habitat protection, and local salaries.

Researchers emphasise, however, that the model succeeds because locals have real decision-making power and strict governance structures, not because trophy hunting inherently produces conservation outcomes.

In Pakistan, animal numbers surged

In Pakistan’s northern regions, trophy hunting of markhor, or screw-horned goat, and Himalayan ibex operates under a CITES — approved community management program.

In these regions, 80 per cent of trophy fees go directly to local communities, with the remaining 20 per cent returning to government conservation programs, according to Pakistan’s Wildlife Department and United Nations Development Programme reporting.

Multiple studies published in conservation journals and CITES case reviews show that markhor populations rebounded significantly in areas where communities controlled revenue and protected habitat.

In 2024, it was widely reported that a permit to hunt a flare-horned markhor sold for roughly US$180,000 ($270,000), the highest amount ever paid for the species.

‘It’s neocolonial’

Robbie Kroger, a South African Australian American hunter and content creator, runs an organisation with a mission to rebrand hunting’s image. He’s furious about Australia’s proposed ban.

"Australia through this ban is acting like a colonialist, actually a neocolonist".

"I cannot defend a rich, fat white person sitting behind an animal," he says. "I can defend this picture of us with all the schoolchildren that we just fed", showing a picture on his phone of himself and three other men standing with a group of schoolchildren.

Kroger doesn’t pretend the model is perfect. But he says hunting keeps land from being cleared for agriculture and in his view, that makes it a trade-off worth taking.

"Forget everything else. If we’re protecting habitat in Africa alone, for example, hunting protects 1.5 million square kilometres of habitat," he told The Feed from Memphis.

"Wouldn’t you want to use every tool we have?"

And he says in some remote areas, it’s the best viable option for generating income.

Kroger pulls out a photo of a local man he calls Peter, who lives in rural Zimbabwe. He says there isn’t a tourism lodge within 100km of Peter. Where tourists won’t go, hunters will.

"He will tell you that hunting elephants has changed his life from a protein perspective," Kroger says.

For Kroger, cruelty happens in nature anyway, so why not get paid for it?

"Mother nature, she’s a cruel, violent bitch. She’ll bring disease, she’ll bring starvation … Are you either going to get someone to pay you to do it or are you going to pay to do it?"

"It simply comes down that they hate the idea of hunting."

'Agriculture in disguise'

Cruise argues that while some species numbers have increased, the context matters.

"A lot of hunting people say our numbers of species are actually going up," he says.

"And that is true, but you’ve just got to look at the nature of what these species are. They’re not wild, they’re ranched."

He describes many hunting ranches as "agriculture in disguise".

"It falls under the agricultural ministry. It is not under the environmental ministry and the profits are agricultural. So admit it as such."

On many trophy properties, Cruise says target species are effectively farmed — artificially fed and selectively bred for larger horns or whiter pelts.

"It’s kind of like cattle ranching where the target species that hunters like to shoot are overstocked on small patches of fenced land," he says. "It’s not really the protection of nature or biodiversity."

A line in the sand

Plumb says that from his own trips, he’s seen the benefits firsthand — and that even if the system has flaws, he believes he’s contributed to something positive.

But he also acknowledges past mistakes, including "taking an immature animal" or "a long time ago, probably climbed over a fence I shouldn’t have".

On one point, Plumb and Beynon agree: a ban like this won’t stop people from travelling overseas to hunt if they really want to. Some within the hunting community told The Feed that Australians had hunted a lion just months ago and plan to bring back a sculpture instead.

"There won’t be any real-world effect," he says. "If a person wants to go to Africa and has the money to shoot a lion, they’ll shoot a lion."

But for Beynon, Cruise, and others pushing for change, that’s beside the point. For them, the ban is about where Australia chooses to draw the line.

Through award winning storytelling, The Feed continues to break new ground with its compelling mix of current affairs, comedy, profiles and investigations. See Different. Know Better. Laugh Harder. Read more about The Feed

Have a story or comment? Contact Us