Tsegaye Arassa is on alert. He's installed security cameras at his home and in his car.

Whenever he sets out on a drive he looks up at his rearview mirror several times during the trip to ensure he isn't being followed. It's a habit he grew accustomed to in Ethiopia.

"[In Ethiopia] there were these security guys following me sometimes," Tsegaye told The Feed.

"I look up at the mirror and immediately commit the plate number of the car behind me into my memory because of that experience."

He believes he's still being watched -- even though he's now lived and studied in Melbourne for almost a decade, having been granted refugee status in Australia because of the risks to him in his homeland.

In the last few weeks, the threat has escalated: he learned that the Ethiopian Attorney General had charged him with inciting ethnic and religious strife in relation to his activities in Australia on social media discussing issues he believes affect the Oromo community in his homeland.

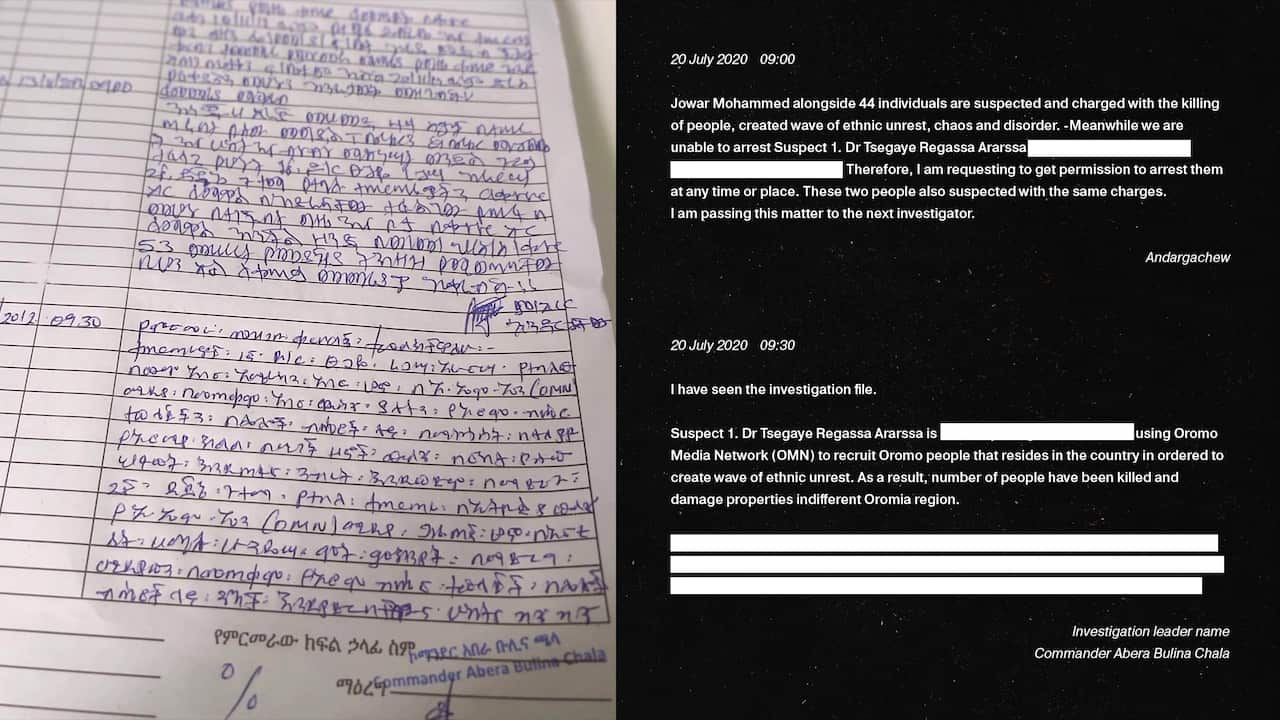

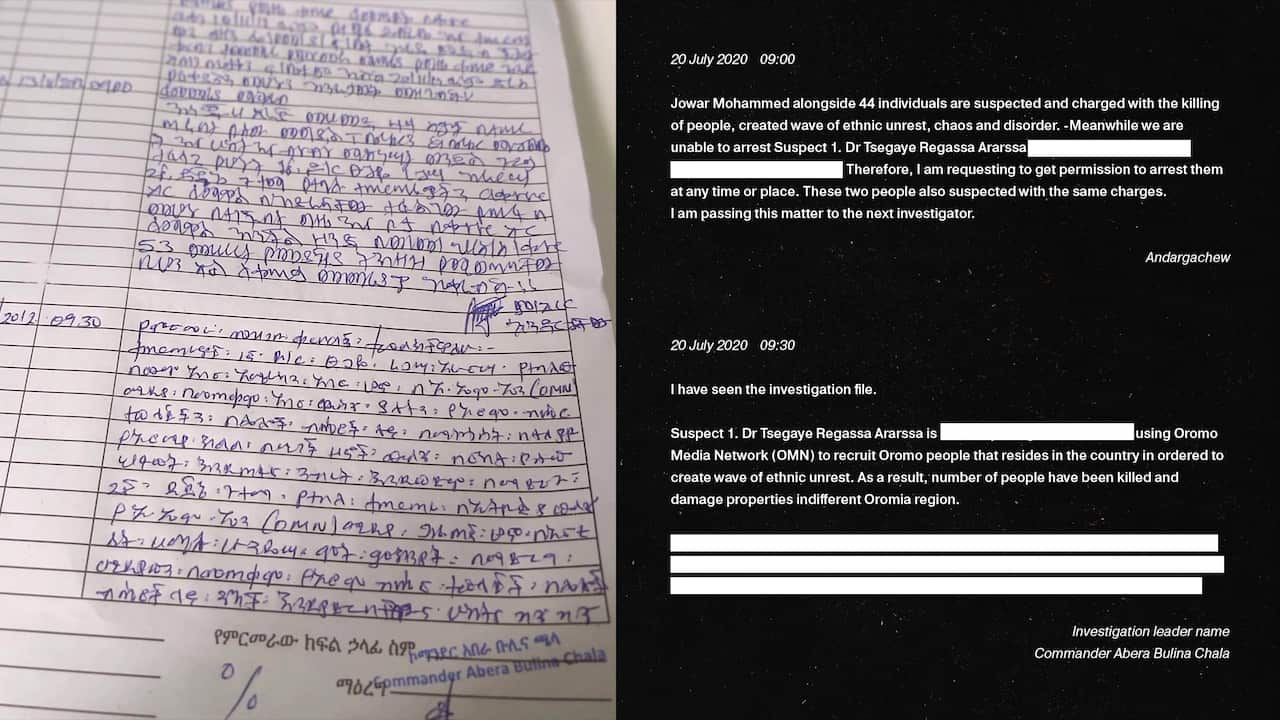

In July, as shown in documents obtained by The Feed, Tsegaye received a warrant for his arrest by the Ethiopian government, while the Ethiopian immigration department requested details such as when Tsegaye left Ethiopia, a copy of his passport and a photo of him.

The documents were sent to Tsegaye from his contacts in Ethiopia. He denies all of the accusations levelled at him by the Ethiopian government.

He denies all of the accusations levelled at him by the Ethiopian government.

An Ethiopian government document obtained by The Feed calling for the arrest of Tsegaye Arassa. Source: The Feed

Tsegaye is a former law lecturer at Addis Ababa University, and is currently doing a PhD at the University of Melbourne's Law School. He calls himself a public intellectual who specialises in constitutional law and federalism. Tsegaye has been a part of a movement to see the Oromo community, a marginalised ethnic group in Ethiopia, access political power in his homeland.

Tsegaye is among many in diaspora communities in Australia who have felt under threat as a result of their political opinions and activism back home. For him, it's been an ongoing issue since he left Ethiopia in 2011.

In August, ASIO revealed there are over 100 religious and ethnic communities that have reported being subjected to threats by foreign governments.

"Some foreign governments seek to interfere in diaspora communities to control or quash opposition or dissent deemed to be a threat to their government," an ASIO spokesperson told The Feed.

"Such interference has included threats of harm to individuals and/or their families, both in Australia and abroad. In some cases, foreign governments will seek to use members of the diaspora community in Australia to monitor, direct and influence the activities of the same diaspora communities.

"ASIO actively works with diaspora communities to help protect them from attempts at foreign interference."

In August, the Australian Multicultural Council raised concerns that refugee communities in Australia are among the most vulnerable to this kind of intimidation.

"The relationship between the countries of origin and refugee communities in Australia may be tense on occasions," the council wrote in their Senate submission.

"It is the responsibility of Australian government to protect refugee communities from attacks on them by the agents of foreign governments."

Security expert calls for Australian foreign interference commissioner

Katherine Mansted is a senior adviser of Public Policy at the Australian National University, and specialises in national security. She believes the public conversation around foreign interference tends to focus on Australia's big picture interests.

"So we think in terms of geopolitics, national security, protecting Australia's sovereignty, but the human story behind this, and human rights issues behind it often get lost," Mansted told The Feed.

"There is growing evidence that Australia's diaspora communities, particularly those from authoritarian and illiberal regimes in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, are being monitored by their former governments.

"And there is a growing kind of body of evidence that there are also incidents where people are either coerced to inform on others or have pressure exerted on their families back home, in order to censor debate and discussion here in Australia."

Mansted believes there needs to be a foreign interference commissioner, similar to Australia's human rights commissioner to increase transparency on potential activities of foreign interference.

"Because this interference thrives in darkness. And if you can throw some sunlight on it, it helps diaspora groups build resilience to it, be able to understand it, see it, push back against it."

'I was a target of a massive global campaign to vilify and mischaracterise me'

Tsegaye, currently a PhD student at the University of Melbourne, says his opinions of the Ethiopian government have led to material consequences all the way to Australia.

"So in 2018, I was a target of a massive global campaign to vilify and mischaracterise me, to literally demonise me. A group which called itself 'Ethiopians for peace' started a social media campaign on change.org and on Facebook," he said. During this period, Tsegaye was in the process of seeking asylum, and was waiting on a protection visa to ensure he would be able to stay in Australia.

During this period, Tsegaye was in the process of seeking asylum, and was waiting on a protection visa to ensure he would be able to stay in Australia.

Source: change.org

"They wrote submissions, they wrote letters, petitions to the immigration authority, asking them to deport me because at the time I was seeking asylum here, and to a certain extent, it delayed the process of my protection visa," he said. He denies all of the allegations that were launched against him.

"They wrote a lot of threats on Facebook and social media calling for my killing, my removal from the university," he added.

"I had to run to the police to report to the Cyber Crime Squad to seek protection."

There have been tensions between successive Ethiopian governments’ and the Oromo community in the country for decades. In 2005, Human Rights Watch reported since 1992 thousands of Oromo people were imprisoned on charges of “plotting armed insurrection” but found those accusations were tactics to imprison individuals who questioned government policies or actions.

“Security forces have tortured many detainees and subjected them to continuing harassment and abuse for years after their release,” the report reads.

More recently, Amnesty International released a report into human rights violations in Ethiopia by security forces in the Oromia and Amhara regions of the country.

Tsegaye took on a bigger role with advocacy and activism from Australia in 2015 when the #OromoProtests began - a series of demonstrations held in response to the Ethiopian government’s plans to extend the city of Addis Ababa into neighbouring Oromo towns and villages.

Tsegaye, along with others, worked on the Oromo Freedom Charter, which calls for peace, independence and self-rule in the Oromia region.

The heightened level of animosity that Tsegaye has felt wasn’t only online. One evening he was walking towards a carpark in Footscray, a suburb in Melbourne’s inner-west.

Then suddenly, he says, “people from dark corners shout my name and they call me names.”

“They use ethnic slurs which basically mean ‘you are rotten Oromo’. It is a pejorative name that Ethiopianists use against the Oromo community. It's like the equivalent of n***** in the United States for example,” he said.

From then on, Tsegaye decided not to visit areas in Melbourne with large east African communities like Footscray.

The threats began to subside for a period but after the political assassination of Oromo artist Hachalu Hundessa in June this year, multiple high profile opposition leaders in the Oromo region were imprisoned, including Jawar Mohamad, owner of the Oromia Media Network.

It was during this time while Tsegaye was being interviewed by the Oromia Media Network, an online media platform, on Facebook Live. He says a message popped up via live comments, telling him that his young son would be kidnapped.

“They called for that assassination they have assured themselves that they will commit it,” he said, “[They said] we know where you are. We are right there to kidnap the kid and to arrest you.”

A few weeks ago, Tsegaye got several calls from a number an anonymous number from his mobile to his landline -- which he says he didn’t answer.

“I've been so abused by phones, by emails by Facebook inboxes. I don't usually [answer] phones [calls] that I don't know,” he said.

After a few days of ignoring calls, his son received a call and rushed over to him.

"He came to me to say 'somebody from the Australian government called and he wants to talk to you', I said 'what'. Somebody from the Australian government in Canberra, called you?"

Tsegaye was alarmed. It wasn't so long ago that his son was being threatened.

The person on the line, Tsegaye says, was someone from ASIO.

"I don't know where he got this idea that I am threatened from, they didn't tell me," he said.

"[He was] asking me what kind of threats and attacks are directed against me and we spoke about it and we are still in touch and I'm going to send him all those things I've sent to the police."

'It's almost like we haven't left the police state'

Sara* fled Sudan when she was only seven years old after one of her parents was captured and imprisoned by former Sudan dictator Omar Al-Bashir.

"My parents were activists, they worked really, really hard for the freedom and safety of the Sudanese people," Sara told The Feed.

One of Sara's clearest memories from her youth in Sudan was in primary school when she was only five-years-old.

"We were at the front of the school gates. And I was trying to explain what unfair imprisonment was to them," she said.

"And there was a security forces car just outside the school. I was terrified but that was normal. Fear was normal when you're monitored by a state and that state wants you dead."

Sara says raids on their house in Sudan were regular, she remembers people coming into her home with and without military uniforms.

"We have a lot of books and a lot of those books weren't allowed. I loved the library, it was my favourite place to be in the house," she said.

"After a raid, papers and books were all over the floor, I thought 'oh my god they killed the library'."

Despite arriving in Australia as refugees in the early 2000s, she still believes her family is being monitored. She says if there's a group discussing issues within Sudan, there most likely will someone there to monitor the group, and take notes of who came.

"If there's a rally, photos will be taken and those photos will be circulated back to security forces back in Sudan," she said.

"It's the fake accounts being made with, like, the names and faces of activists that slander and destroy their reputation.

"It's almost like we haven't left the police state. The police state followed us. And it's also terrifying because you don't know who to trust in your community and who you can say something around."

'The police couldn't protect me. Nobody could protect me'

The federal government has put in measures to track foreign interference. Last year, the government set up a counter foreign interference taskforce. Currently, ASIO are in contact with over 100 different ethnic and religious groups trying to identify risks within diaspora communities.

Despite this Tsegaye has lost faith in Australian institutions, and isn't sure whether Mansted's recommendation of a foreign interference commissioner is something that can help his situation.

The only thing that will help Tsegaye, he says, is stopping the threats.

He says they have impacted almost every corner of his life; his mental health, his family, his career, his political action and immigration status.

"The police couldn't protect me. Nobody could protect me," he said.

"I have been to the police for four years now. The police only say there isn't any physical harm so far. Right? So okay, we can't do anything, just watch yourself and delete your social media activity.

"The police can't help you, what does ASIO do for you? What does a commissioner do for you? I really don't understand I mean, you know, it's a nightmare you live alone, that's all and you're not free. Nobody is here to help."

*Name has been changed

Share

Through award winning storytelling, The Feed continues to break new ground with its compelling mix of current affairs, comedy, profiles and investigations. See Different. Know Better. Laugh Harder. Read more about The Feed

Have a story or comment? Contact Us