Like so many farming regions these days, Robinvale in Victoria depends largely on one crop – this sleepy little town is the epicentre of Australia’s $500 million almond industry.

“While this might be a very efficient way of growing crops, unfortunately, it’s very hard on many native insects,” says Dr Tim Heard, Entomologist.

When the almond trees come into bloom, Robinvale looks like a picture of health. But aside from the almond trees, the landscape is lifeless – animals depend on insects and insects depend on plants. So when there’s no diversity at the base of the food chain, ecosystems struggle.

To that end, Robinvale’s almond farmers rely on shipping in bees to pollinate their crop.

Trevor Monsoon co-ordinates Robinvale’s pollination party. And it’s a big party. Bees from all around Australia are invited. “I have 185+ beekeepers on the books that I deal with. They vary from 20 hives of bees to 5,500 hives,” says Monsoon.

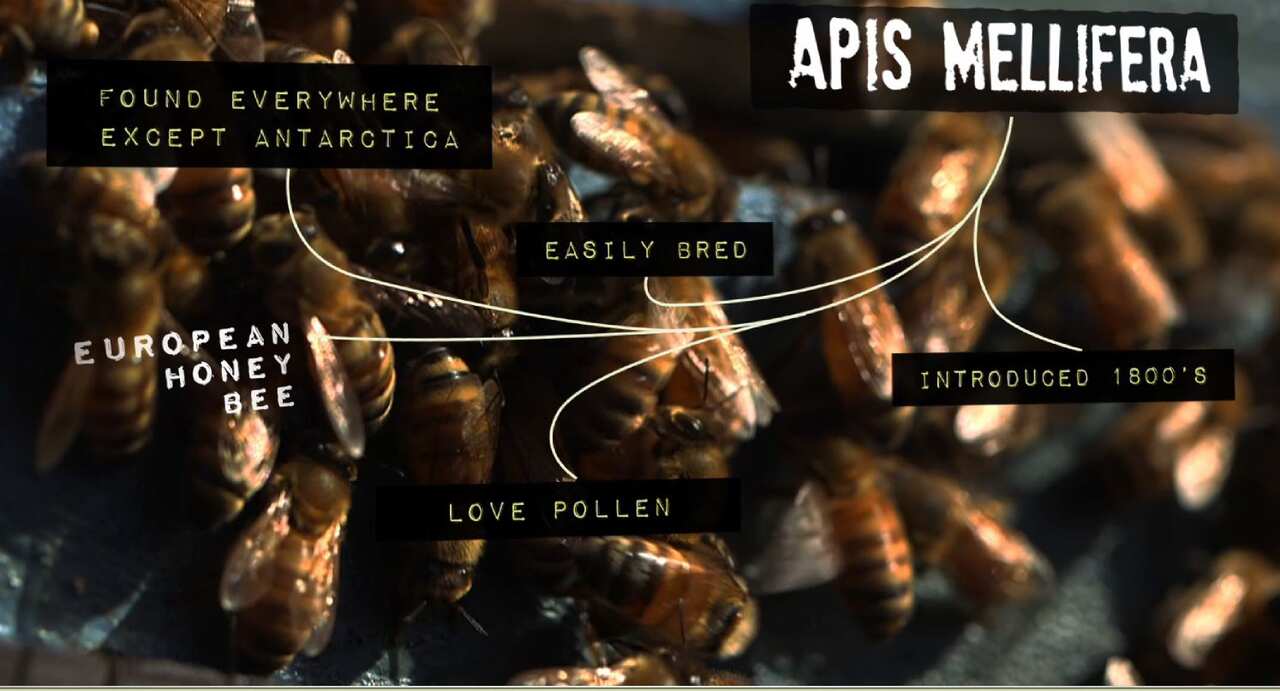

Australia has around 2,000 native bee species, but it’s the European honey bee that powers commercial agriculture in this country.

Generally speaking, the European honey bees working the fields in Australia are pretty healthy. They have developed resistance to most global diseases except the varroa mite, a tiny parasite that inhibits the bee from collecting pollen and feeding its young.

Everywhere around the world where the varroa mites have spread, bee populations have diminished and the price for pollination has increased substantially. Of course, that cost is then passed on to the consumer.

It’s time we start cultivating contingency colonies of native bees.

Experts talk about the arrival of the varroa mite in Australia as a matter of when, not if, and it’s time we start cultivating contingency colonies of native bees.

However, while native species are more disease-resistant than the European honey bee, they are not a sure-fire substitute. Firstly, there just aren’t enough native bees to do the work that European honey bees currently perform. Secondly, native bees struggle to perform in cold climates; so farmers in the southern half of Australia won’t be able to rely on shipments of native bees to pollinate their seasonal crops.

Farmers like Brett Newell are future-proofing our food supply by designing portable hives that allow native bee colonies to be managed. Meet Brett in the video below:

#TheFeedSBS airs 7.30pm weeknights on SBS VICELAND. Live Stream | Facebook | Twitter

Through award winning storytelling, The Feed continues to break new ground with its compelling mix of current affairs, comedy, profiles and investigations. See Different. Know Better. Laugh Harder. Read more about The Feed

Have a story or comment? Contact Us