For centuries the fabled city Samarkand has been a magnet for merchants, travelers and conquerors. Set in the valley of the Zerafshan River in Uzbekistan, this turquoise oasis still beguiles modern-day visitors following in the footsteps of Alexander the Great and the mighty Tamerlane. Reflecting its past as a cultural crossroads, this Silk Road stopover has buildings, gardens, fountains and other cultural treasures whose extraordinary beauty and achievement inspired Islamic architecture across the entire region – from the Mediterranean to India. Sky-blue mosques and sand-coloured minarets, fluted domes, madrasas and monumental mausoleums, their ceramic-tiled and mosaic surfaces dazzling with floral motifs and geometric patterns – the effect is as dizzying and utterly compelling as a mirage in the desert.

For hundreds of years the journey to Samarkand necessitated a Herculean effort. Arduous expeditions, carrying goods between far-off cities like Xi’an and Shiraz, made the trek on two–humped Bactrian camels over endless steppe, through inhospitable mountains and across shifting sands like the Taklamakan Desert, a parched expanse roughly the size of Italy.

Why? What made men endure scorching heat, numbing cold and howling winds, losing their minds – and lives – in a bid to reach Samarkand, hidden behind a barricade of mountain, grasslands and sand? The answer is trade, because from the sixth to the thirteenth centuries Samarkand experienced an age of unmatched prosperity. It became Asia’s great shop window, one of the world’s finest marketplaces, where everything from rare spices to yak-tail fly whisks were bartered and sold.

Throughout the centuries the wealth of Samarkand has been legendary. Merchants sought bags of rice and carrots from the Himalayas, cuts of sugar cane, bundles of lemons, plaits of garlic and sacks of soy beans from eastern Asia. Exchange on the Silk Road travelled in both directions too.

Traders found safety in Samarkand in the form of shelter, dealers and brokers. Mercenaries too could be hired for the onward journey to fend off slave raiders and bandits. Long after the merchants had departed their good and traditions stayed on in this oasis. Sogdian – the language of Samarkand’s middlemen – became the language of the commercial world. This is a city that been at the crossroads of food culture for centuries.

Modern-day Samarkand is no longer the mythical place it once was but the journey to this incredible city is always an exciting one.

Siyob Bazaar, Samarkand. Source: Getty Images

Seven cuisines

Seven ethnic groups have left their mark on Samarkand over the centuries – the Tajiks, Russians, Turks, Jews, Koreans, Caucasians and the Uzbeks themselves.

Tajiks have lived in Samarkand and Bukhara for centuries and large numbers still do. In mountainous Tajikistan itself, bordered by Kyrgyzstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the northwest, Afghanistan to the south and China to the east, their cuisine displays a mix of Russian, Uzbek and perfumed rice dishes, reflecting Persian roots.

A sizable population of ethnic Russians continues to live in post-Soviet Central Asia. Smoke and brine – traditionally used to preserve food in Russia – infuse the air in homes and restaurants. Sweet earthy borscht and piroshky (fried buns stuffed with potatoes and meat) are ever-present in markets and cafes.

Turks have traded and lived in the region for centuries and Turkish cuisine is imitated and admired across Central Asia. Nowadays, popular Turkish restaurants in the Central Asian region tend to serve pides – similar to pizza – mutton casseroles, spitted and grilled lamb, while kebab varieties run into the dozens.

There are Jews living in Bukhara and Samarkand who claim to be direct descendents of the ten lost tribes of Israel, although historians suggest it is more likely that they arrived at the behest of the fearsome tribal leader, Tamerlane. As he blazed a trail through Asian in the fourteenth century, he brought Jewish dyers and weavers from the Middle East back to his splendid blue tiled city of Samarkand. Over time, oppressive leadership and collapse of the Soviet Union meant that these Jews became one of the most detached Jewish communities in the world. Through it all, many culinary traditions were guarded and preserved, even though today, only around a thousand Jews remain in Uzbekistan. Uzbek Jewish cuisine is a comingling of Persian vegetable-studded pilafs and Russia’s heavy meat dishes. It is characterized by light spices – a little cumin, coriander, turmeric, pepper and chilli – and delicate flavours intensified by herbs, onion and garlic.

The people of Central Asia have never developed a taste for fiery food but one exception is the Korean diaspora, known as the Koryo-Saram. Stalin deported half a million Koreans to Central Asia during World War II, many of whom stayed on and have become the purveyors of pepped-up flavours. Dishes like pickled cucumber and beef ribbons give more than a nod to chilli, and cabbage-heavy kimchi – Korea’s national dish – is increasingly popular in Central Asian capitals.

The Caucasians – Georgians, Azeris and Armenians – are all historically connected to Central Asia. During the Persian Empire, fierce Armenian warriors left their homelands to travel the Silk Road, fighting beside local warlords in exchange for trading rights. Clergy from the Caucasus also left their monasteries to join far-flung theological debates. During the fourteenth century, a group of Armenian clergy travelled as far as the Chinese border to build a monastery named after Saint Matthew. They took their culinary traditions with them and many cultural interchanges resulted. Small communities of Armenians reside in all the nations of Central Asia.

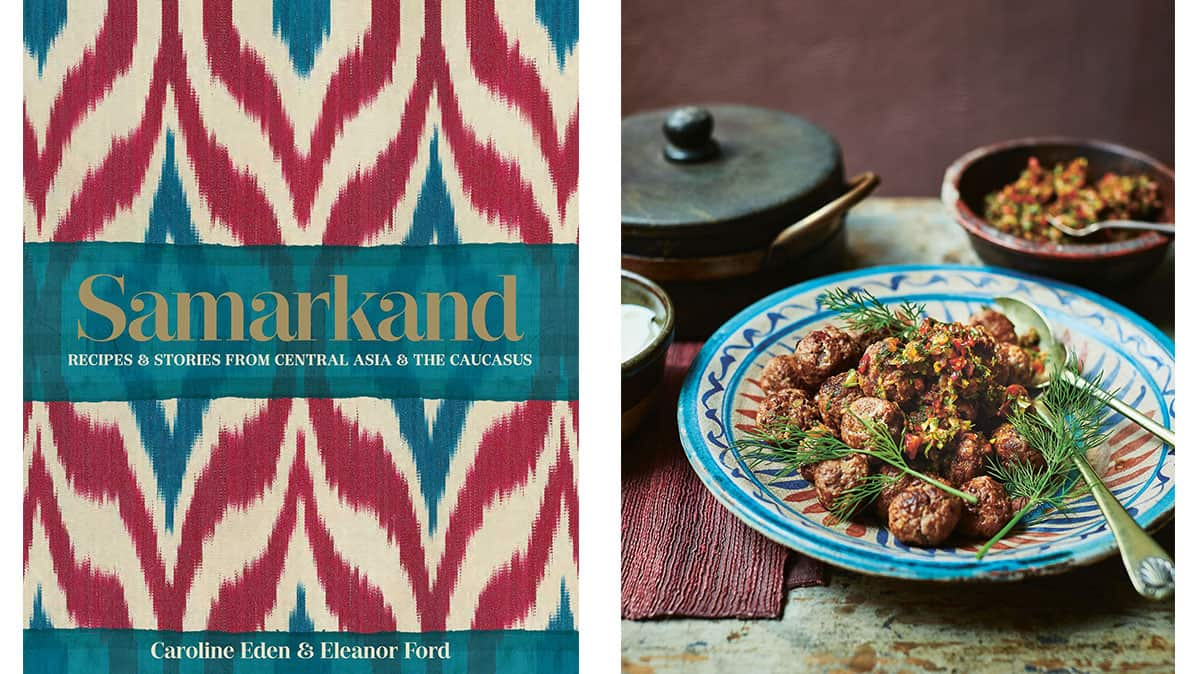

Source: Laura Edwards / Kyle Books

Dazzling bazaars, golden bread and a blanket of stars

When I first arrived in Samarkand in 2009, weary from exploring the Pamir Mountains, its atmosphere shook me. The skyline is filled with monolithic Soviet blocks, colossal sky-blue domed mosques and pale desert-hued minarets. At street level, tangled bazaars overflowed, cauldrons of plov bubbled on the side of the road and butchers hacked away at the sides of beef on tree stumps used as cutting blocks. Melons the size of a horse’s head were crammed into the boots of Lada cars, shop fronts were festooned with dizzying bolts of ikat and suzani fabric bearing pomegranate motifs, while legions of babushki (elderly ladies) pushed vintage prams which carried not mewling babies but golden discs of bread. It’s like time travel, I said, echoing the words of countless travelers before me.

At daybreak, before the arrival of pilgrims, I had wandered alone in the otherworldly necropolis of the Shah-i-Zinda as imams chanted. That night, I ate tandoor-fresh bread and sliced crescents of juicy melon with a jewel-handled knife beneath a blanket of stars. Can any other place on earth provide such a feast for the senses?

Over the ensuing years I completed a dozen or so trips to Central Asia, Turkey, Russia and the Caucasus. On these adventures I dined in mountain villages, in city centres, by glittering lakes and out on the steppe. I ate borscht while playing backgammon with war veterans in Soviet-style canteens, slurped gently seasoned laghman (noodles) in yurt cafes and enjoyed unending hospitality in people’s homes. By avoiding the ‘tourist’ restaurants it is easy to eat well in the former Soviet Union; hospitality is a cult in all these countries. It oils the wheels and it is justifiably legendary. In Samarkand, you can expect a genuine welcome, for ‘the guest is the first person in the home’.

I fast discovered an enormous diversity of food cultures, from Russian-style borscht to Turkish-style shashlik, and dished that at first seemed familiar but were not – like the omnipresent plov, which is similar to a Persian pilaf, and samsa, which is like an Indian samosa. Everywhere I went I feasted on fruit fit for kings – all of it always criminally cheap. The aromatic apricots in the Pamir Mountains of Tajikistan, the famous golden peaches of Uzbekistan and the bullet-shaped grapes in Kyrgyztan, made me realized what we in the West have lost in flavor in the name of convenience. Most of all, I discovered that this food culture straddles many borders is a bit like matryoshka, those brilliantly kitsch Russian dolls. As soon as you unveil one, another presents itself. And at the heart of it all was Samarkand, which has sat at the crossroads of food culture for centuries. As a mere city its location is narrow but its scope is extraordinarily wide.

Edited extract from Samarkand by Caroline Eden and Eleanor Ford (Kyle Books, $49.99), available now.

Cook the book

Suzma is a tangy yogurt cheese, which is spooned into soups, mixed into salads or eaten with bread and fresh tomatoes as a simple meal.

Source: Kyle Books / Laura Edwards

All over the Caucasus, people traditionally stuff aubergines with walnuts and pomegranate seeds to be pickled and preserved for the long winter months. This is a fresh version of the Georgian dish badrijani nigvzit, using grilled aubergines instead, but with the same flavours.

Source: Laura Edwards / Kyle Books

Adjika, literally ‘red salt’, is a spicy and fragrant pepper paste from Abkhazia, a breakaway region of Georgia. You’ll find it completely addictive.

Source: Kyle Books / Laura Edwards

Throughout Uzbekistan different cities and provinces product their own distinctive non - the word is Persian, pronounced nahn. It is usually baked on the searingly hot clay walls of a tandoor oven. At home, using a pizza stone and the oven cranked to maximum is the best way to achieve the characteristic chewy elastic texture.

Source: Laura Edwards / Kyle Books

Share

SBS Food is a 24/7 foodie channel for all Australians, with a focus on simple, authentic and everyday food inspiration from cultures everywhere. NSW stream only. Read more about SBS Food

Have a story or comment? Contact Us