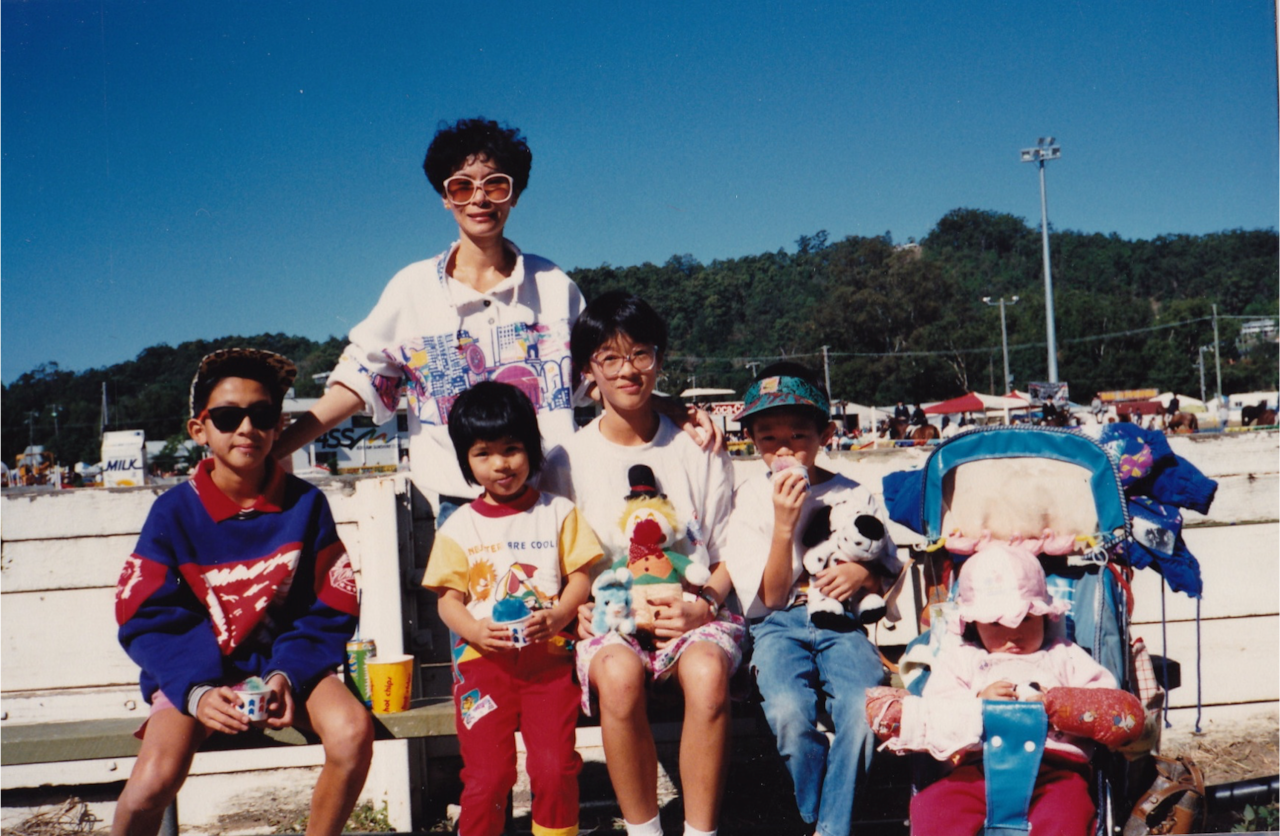

Children take care of themselves at a certain point, especially if you have a few of them. Like most Asian kids, my four siblings and I were supervised and well-behaved, but the sheer volume of us also meant that we had just enough freedom to go slightly feral sometimes. When my baby sister was a toddler, she would do massive poos in the corner of the dining room and hide them behind curtains, applauding stupidly when we eventually found them, screaming. On school holidays, we’d go on neighbourhood expeditions where we’d tie our bikes together with 'occy’ straps, before scraping off half our shins as soon as we started pedalling downhill. We’d also look for weird fish in the canal, get our hands dirty with mud and parasites, before walking to the shops to touch strangers’ dogs on their wet noses. My mum was constantly telling us to wash our hands, but I’d occasionally use those unwashed hands to shovel food into my mouth. Kids are sort of gross – I’m surprised more parents don’t douse them with Dettol at the end of each day.

Needless to say, we were all prone to getting sick. And when one of us got ill, we passed around the same old germs like a badly kept secret. We dragged each other along the bitumen and bled; we got food poisoning together and spewed. We had vomited so much that we had buckets specially reserved for it. Worms, lice and chickenpox came and went, ravaging us all in two intense waves of rashes and Pinetarsol baths. Every other day, there was a sibling spitting out a tooth or walking around with a bloody nose, while common colds descended on us like something biblical.

Early on, our family doctor – this bald, Indian dude named Dr Pratap – told my parents that when we were sick, one of the best things they could give us was flat lemonade or Lucozade. These became standards when we were recuperating. Their gentle hiss and syrupy smell would combine with the odour of Vicks VapoRub and foong yau, this intense Malaysian oil made of menthol, camphor, eucalyptus and lavender that Mum would rub on our stomachs when we had a stomach ache or felt nauseous. Even now, smelling any of those things immediately makes me feel better.

The one other smell that still has the same effect is boiling rice. Its aroma wafting into our bedrooms meant Mum was making congee, something that would take the entire day to do properly if we didn’t already have cooked rice left over. Every family has its own thing for sick kids: Jewish mothers make chicken soup; Asian mothers make congee.

A lot of Westerners are unfamiliar with the stuff, but if you come from an Asian background – whether Japanese, Malaysian, Indonesian, Vietnamese, Burmese, Korean, Filipino, Sri Lankan or Chinese – you’d have your own version.

This chicken congee (arroz caldo) is a Filipino version of this Asian staple.

My Cantonese family called it jook (rhymes with 'book’), which was rice boiled with so much water that it broke down to become the consistency of a slick porridge. It’s what a lot of Asians have for breakfast and what we crave when we’re so sick, we can’t hold anything else down. It makes sense – the key ingredients are two of the most digestible substances in existence: water and rice.

If you go to your local Chinatown, you’ll find restaurants that specialise in the stuff. In Sydney, there’s one hokey-looking place that offers so many varieties of congee they have four menus for it all. Besides the basic congee, they’re able to pack in pillowy-soft fish fillets, razor-thin slices of ginger and spring onions, gravelly combinations of minced pork and peas, paper-thin offal, chunky squid strips, shredded chicken and egg whites whisked into ribbons. They also have pickles that’ll make you wince with both the flavour and the concept; pickled turnip strips smell like dog’s breath. Century eggs – equally feared and loved – are fermented in ash, clay, lime, rice hulls and lots of salt, until the eggs turn black like something cauterised. They smell horrible, look like hell and taste incredible.

But for me, the best accompaniments are the long, deep-fried dough sticks you can dip into the congee. The Cantonese call them yau ja gwai, and they’re the kind of oily, crisp, salted goodness that can make napkins transparent and eventually give you a heart attack if you’re not careful with your level of consumption.

During my travels travels through Asia – Thailand and Japan, China and India to name a few countries – I keep finding variations of the comfortingly familiar. In Cambodia, I contracted a stomach virus that nearly sent me to hospital and gave me these intense, pulsing cramps that were so painful, I actually lost consciousness. I was convinced I had contracted the same dysentery that had infected my fellow volunteers, but after 30 hours passed out and sweating on a bed, I slowly made a comeback. The first thing the hostel served me was what they listed on the menu as 'rice soup’. The rice was barely broken down and floated in the stock, but it was still what I was looking for. It was congee, Cambodian-style.

Cure in a bowl: feel better by making a bowl of Chilli and garlic congee with shitake mushrooms

Grief is a type of sickness, too. In my mind, the world is divided into two groups of people: those who can’t stop eating when they’re sad, and people who starve their way through it and can’t possibly imagine eating anything again. In Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – her memoir about the death of her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne – she recalls how her friend, author Calvin Trillin, knew her well enough to anticipate that she wouldn’t be able to eat properly after John had suddenly died. "Every day for those first few weeks," Didion writes, '[Calvin] brought me a quart container of scallion-and-ginger congee from Chinatown. Congee I could eat. Congee was all I could eat."

My friend Romy, who’s a writer and a cook, wrote about grief and eating in an essay, and quoted the famous American food writer MFK Fisher. In Fisher’s book, An Alphabet for Gourmets, there’s a chapter called S is for Sad, where she talks about 'the mysterious appetite that often surges in us when our hearts seem about to break and our lives seem too bleakly empty".

Romy wrote that trying to reconcile food with mourning is a difficult concept. 'To be ravenous," she wrote, 'could be seen as an affront to the dead. Nothing says living like succumbing to the need for sustenance – hunger."

I’ve been lucky enough not to experience too much death in my family, but already I know that when the inevitable happens, I won’t be able to eat. The only thing I’ll be able to stomach will be congee, and my family will make big vats of the stuff.

Growing up, Mum’s version of congee was always super-simple: white rice, cooked until it was waat (the Cantonese word for slippery or smooth), served with a couple of drops of sesame oil, a splash of soy sauce and lashings of ham choy – 'salty greens’ that are actually mustard plant leaves pickled in salt and vinegar, which smell like wet rags marinated in a sour mixture.

Nowadays, when we visit my mother, she’ll often have a giant rice cooker of congee waiting for us when we park the car. She’s changed a few things though, and her signature congee now boasts softened peanuts and whole mussels, as well as the requisite ginger that’s been there from the start.

I can tell you now: there is nothing more fortifying than a bowl of this stuff, and nothing more satisfying than trawling the bowl to retrieve a juicy mussel out of the goop, dripping with soupy goodness and laced with soy and shallots. And to think: all you need to do is boil rice; it’s a recipe with a single step. Most of the time, I can’t think of anything better to eat.

More of Benajmin Law's childhood memories come back to life in The Family Law season 2. Tune into SBS for the brand new second series starting Thursday 15th June at 8.30pm. Find more about the new season, plus articles by Benjamin Law and his mother Jenny Law, here.

SBS Food is a 24/7 foodie channel for all Australians, with a focus on simple, authentic and everyday food inspiration from cultures everywhere. NSW stream only. Read more about SBS Food

Have a story or comment? Contact Us