In Brief

- New analysis shows federal and state debt is on track to reach World War Two levels.

- Higher debt can result in poorer public services and undermine living standards.

Australia's federal and state debt is rising, according to a new report, placing the country at financial risk in "unprecedented times".

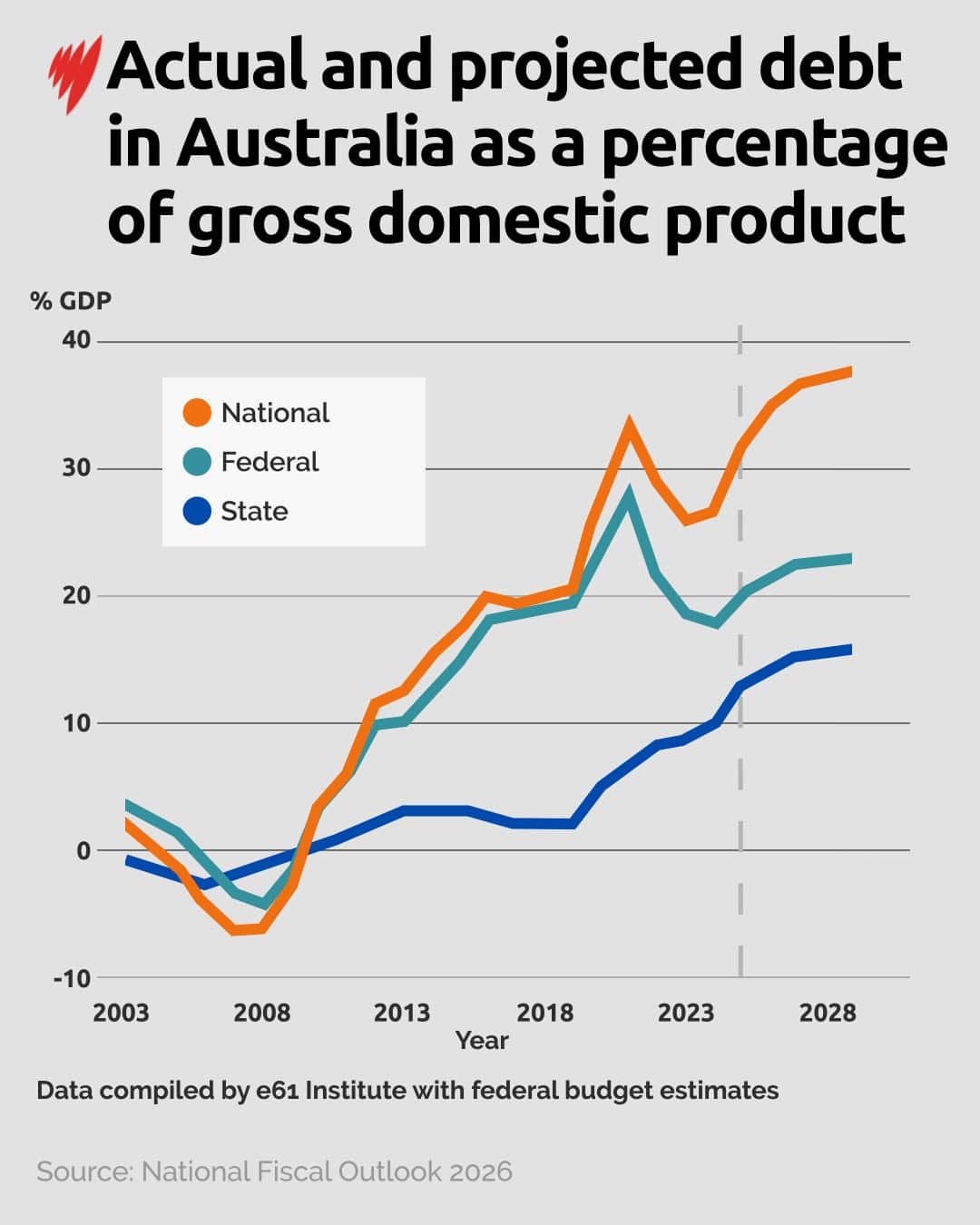

New analysis from economic think tank e61 Institute suggests Australia is on track to see debt reach 37 per cent of the nation's gross domestic product (GDP) in two years.

The group's CEO, Michael Brennan, said the rising levels of debt would impact the government's ability to invest in services and burden future generations.

"When you have greater levels of debt, it restricts your ability to invest effectively in different sectors," he said.

"Spending more in one area, such as health and education, means spending must then contract in other key services, such as the police."

If combined federal, state and territory government debt reaches the think tank's projection by 2028, it would be at its highest level since World War Two as a share of the economy.

What is driving up debt?

Brennan said that as GDP increases, it's common for governments to spend more on social systems.

"It's a fair social expectation from Australians that a wealthier country should invest more in quality healthcare and education," he said.

Public expenditure has increased from 34.7 per cent in the early 2000s to 38.2 per cent in 2024, covering spending by federal, state and territory governments, according to the report.

Social services represent the largest area of expenditure, encompassing welfare benefits, childcare assistance and the NDIS. They make up roughly one quarter of total outlays. Health ranks second, followed by education.

Per capita health expenditure has doubled since 1999, while spending on education has remained steady.

The report argued the expansion in social spending stemmed from a move away from tightly means-tested benefits, such as family payments, toward "in-kind" support — like the childcare subsidy and the NDIS, which are less focused on low-income recipients.

"Across the board, debt has been rising, and it's in part due to universal systems that don't do means testing, which are expensive and inefficient," Brennan said.

Others argue that universal services improve access and reduce stigma, and can deliver long-term economic and social benefits.

Tax reform and spending restraints are two ways the government could look to reduce debt, according to Brennan.

The government also needs to look at where it can build savings into its current systems, he said, which could look like running programs with fewer physical staff.

How do countries acquire debt?

Flavio Menezes, a professor of economics at the University of Queensland, explained that countries like Australia acquire debt to finance budget deficits when spending exceeds revenue from taxes and royalties.

Budget deficits can be "desirable and necessary", he said, when providing financial support in response to major shocks like a natural disaster or pandemic to stimulate the economy.

However, a budget surplus paired with a "healthy economy" can prevent government demand from crowding out private demand, thereby easing inflationary pressures and reducing debt.

While deficits and surpluses can both have advantages, Menezes said global "shocks" in recent years make navigating debt harder for the government.

"We are living through unprecedented times," he said.

"The energy transition represents the most profound structural transformation in human history. It is unfolding in the aftermath of major global disruptions: the financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic …

"These shocks are compounded by longer-term structural trends, including population ageing and decline, as well as newer phenomena such as slowing global trade and increasingly fractured geopolitics."

Who is this debt owed to?

Menezes explained that government debt is owed primarily to investors — both domestic and international — not directly to other governments.

In Australia, borrowing occurs mainly through:

— Commonwealth Government Securities: Bonds and Treasury notes issued by the Australian Treasury on behalf of the Commonwealth and sold via auction

— State "semi-government" bonds: Issued by state borrowing authorities and backed by state revenues

Whoever buys these securities is the creditor. In practice, this includes:

— Domestic institutional investors: Superannuation funds, banks, insurers, and asset managers

— Foreign private investors: Overseas pension funds, insurers, and global asset managers investing as part of portfolio allocation decisions

— Foreign central banks: Holding Australian government bonds as foreign exchange reserves

What does more debt mean for the country?

As global uncertainty continues and the government looks to support people through economic ups and downs, public debt levels are likely to remain structurally higher than in the past, according to Menezes.

"Higher public debt is to some extent unavoidable," he said.

"It can affect the economy through several channels: rising interest payments may crowd out essential public spending over time, and political constraints can limit governments' ability to adjust fiscal settings in the future, particularly if debt continues to grow faster than the economy."

What ultimately matters, he said, is how the debt is used and whether economic growth exceeds the real interest rate on government borrowing.

"When public debt finances productive investment and supports long-term growth, higher debt need not undermine living standards.

"By contrast, if debt funds are low-return spending in a low-growth environment, it can place sustained pressure on future incomes, public services, and living standards."

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.