In Brief

- CEO remuneration has surged, with the top 300 chief executives leading companies on the ASX earning an average of $3.86 million.

- But the average full-time Australian adult worker earns roughly $107,172 a year.

The wage you earn is not always a reflection of how hard you work, and there are some key factors experts say can influence your pay.

Employee Earnings and Hours data released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) on 23 January provides a snapshot of the most highly paid Australians, as well as the hours they are paid for.

Workplace expert John Buchanan of the University of Sydney says wages can reflect how labour markets work with higher pay for more sought-after skills, but there is also an ethical element to the debate around how much people should be paid.

I think the relative pay structure is problematic these days because people at the top have been rewarding themselves in ways that are out of kilter with what's been going on with inflation and productivity.

Buchanan points to senior managers and chief executives, including university vice-chancellors, on salaries of more than $1 million.

He says the difference in pay between vice chancellors and other academic staff has widened.

An Australia Institute (AI) analysis released last year found vice chancellors in Australia were among the highest-paid in the world, with average wages reaching nearly $1.3 million by 2023. Their wages have almost quadrupled since 1985, when they were paid $300,000 on average (based on 2024 figures, adjusted for inflation).

In comparison, median wages for other workers in the university sector have risen by just 39 per cent, from $62,159 to $86,673.

Some professions are 'massively overpaid'

Buchanan says the increase for vice chancellors reflects a broader trend around executive pay.

Chief executive officer (CEO) remuneration surged last year, according to a survey released by Odgers and OpenDirector. It found the top 300 chief executives leading companies on the Australian Securities Exchange were earning an average of $3.86 million, up 10 per cent from the year before. (Total remuneration includes base salary as well as any allowances, superannuation, bonuses or commissions.)

However, "realised pay" can be higher because it includes funds received when options and shares vest.

As reported by the Australian Financial Review in November 2025, Australia's top-earning CEO last year was Develop Global's Bill Beament, who took home $59.6 million in realised pay — partly because options in the company were converted into shares.

Buchanan says those in the finance sector also enjoy higher wages because they have access to the large amounts of cash flowing through the industry.

"They're not making the economy any more efficient," he says.

I think you've got to stand back and say 'what's fair?'

Similarly, Buchanan says managers are able to "extract money out of cash flows they've got full visibility of".

"I think executives, key parts of the finance sector, and key parts of — particularly in the private medical sector — are massively overpaid."

Employees who work the longest hours

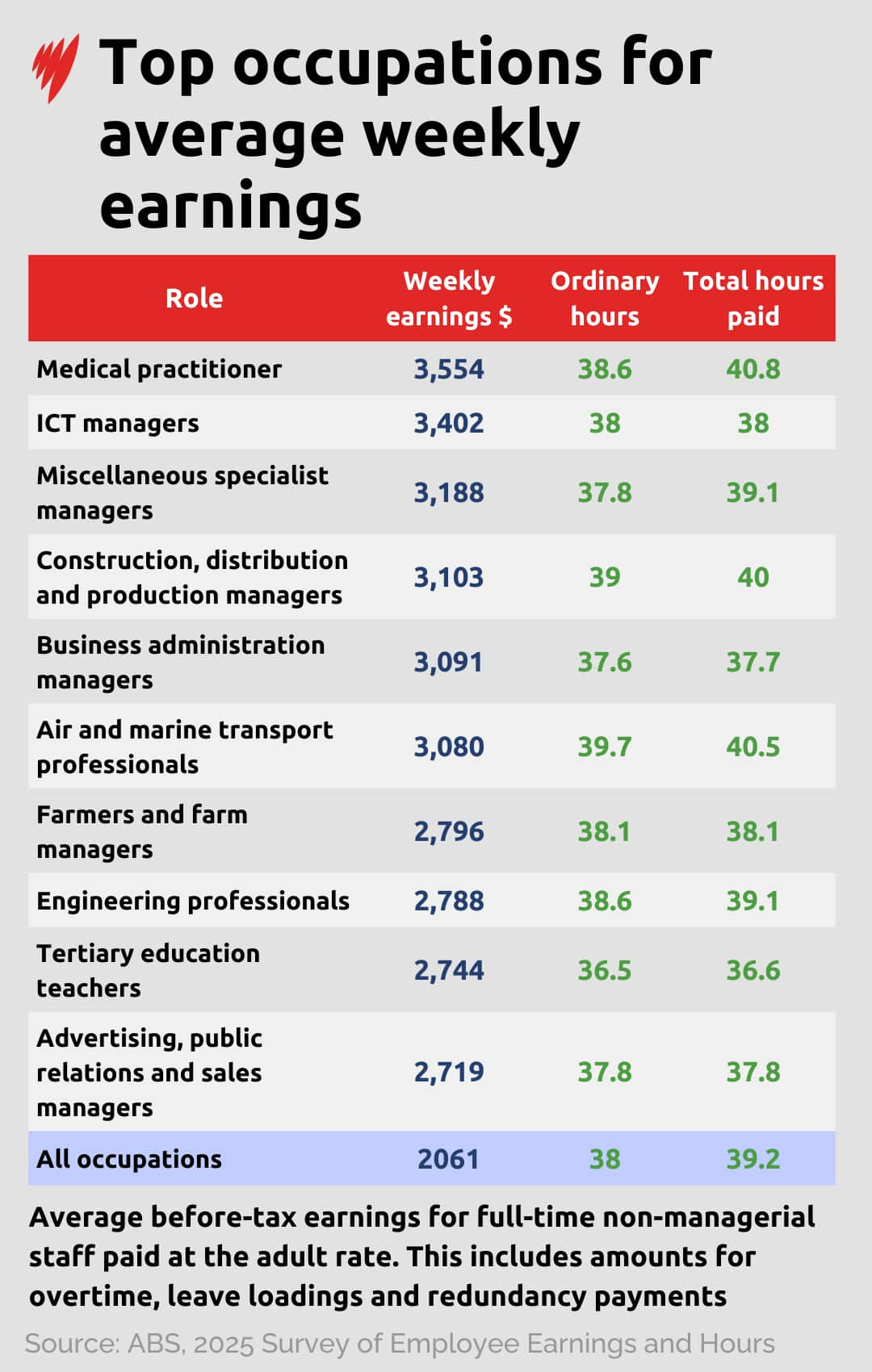

If you exclude chief executives and other high-level managers who have strategic responsibilities or oversee a significant number of employees, the average full-time Australian adult worker earns $2,061 a week before tax, according to the ABS. That's roughly $107,172 a year.

Their "ordinary time hours" are 38 hours per week for those working full-time. These agreed hours of work don't include overtime payments, leave loadings or redundancy payments.

If you include paid overtime, figures for "total hours paid for" show adults work an average of 39.2 hours a week.

None of those who work the longest hours feature among the highest-paid workers.

Truck drivers, who work 46.5 hours a week on average — much more than the overall average of 39.2 hours — earn $2,078 a week before tax.

The top earning profession in Australia is medical practitioners, who earn on average $3,554.10 per week, and work around 40.8 hours.

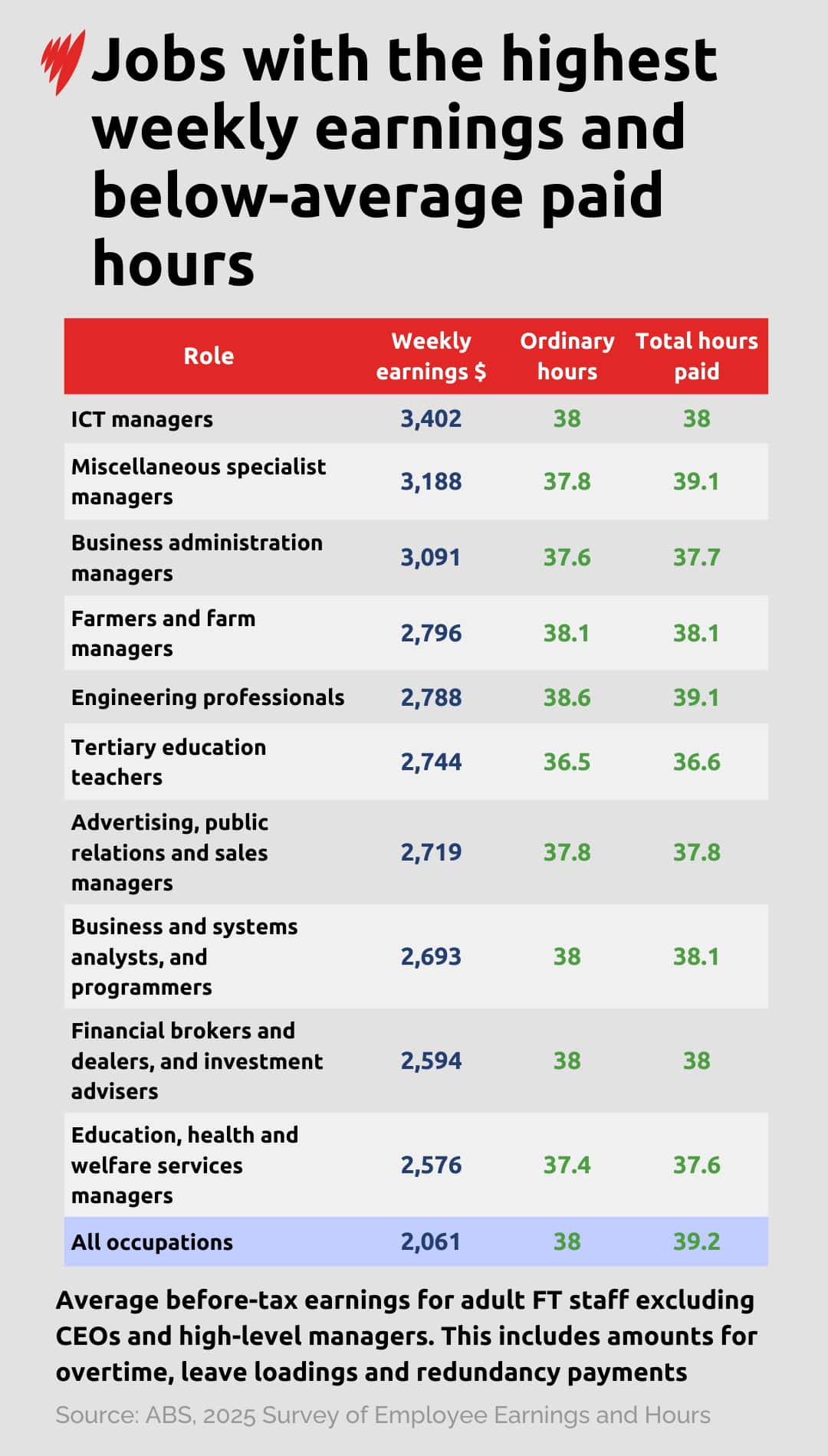

Several occupations with the highest earnings clock below-average paid hours.

These include miscellaneous specialist managers (specialist managers not classified elsewhere, including high-level officers in military, police and fire services); business administration managers; tertiary education teachers; as well as advertising, public relations and sales managers.

The working hours and average pay of chief executives and other high-level managers are not included in this data. A spokesperson for the ABS says it's drawn from a sample size of 50,000 jobs and "doesn't support this level of detail".

Employees who work the shortest hours

Among those who had the lowest paid hours, only one profession also appeared on the list of top earners — tertiary education teachers.

But experts say figures for paid hours may not reflect actual hours worked.

Associate professor in economics at Queensland University of Technology, Leonora Risse, points out that academics often perform unpaid overtime, such as marking student assignments and responding to student emails.

"Often you're doing research papers or ... when inspiration hits you're going to sit down and write. You [also] do your readings," she says.

"You're not going to wait until you're officially clocked on.

"Whereas if [your job involves going] to the site and you can only do that job on-site — whether it's retail or it's mining — when you clock off, you clock off."

This means that for jobs that require you to be on-site — such as those in construction or mining — you are also more likely to be paid for any extra hours.

Why are some people paid more than others?

When it comes to high-paying careers, Buchanan says some are justified by the high level of skills and education required, while others are industry-specific.

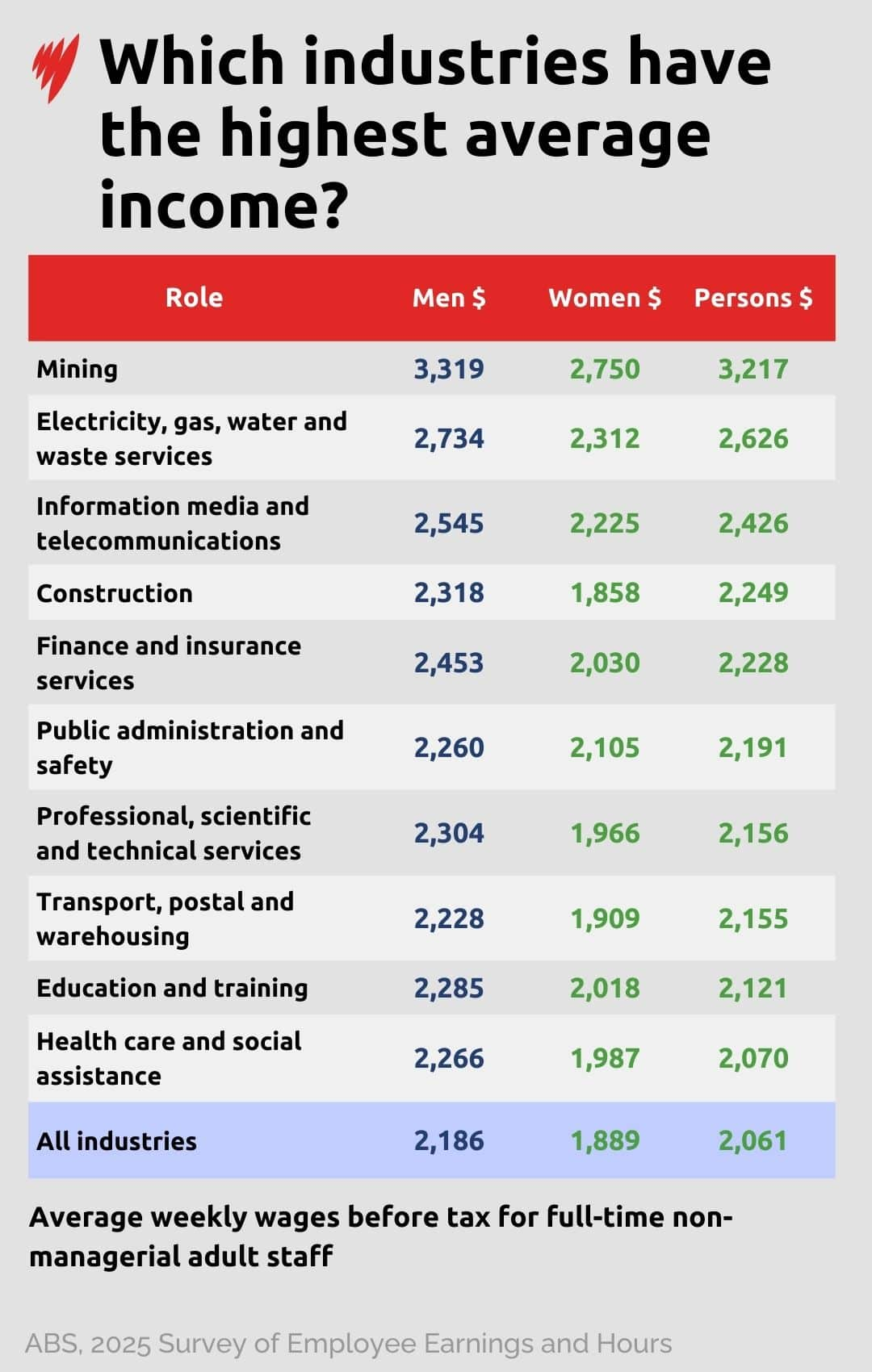

He notes mining — the highest-paid industry on average — is very capital-intensive and requires large investments in infrastructure and other assets to operate. But its product can be produced with few employees, which means workers can be well paid without dramatically impacting overall operating costs.

Around two per cent of the working population 17 years and older are employed in the mining industry in Australia. 18 per cent are employed in healthcare and social assistance, and 10 per cent are in education and training.

The relatively low number of employees in mining also makes the industry more vulnerable to stoppages or union strikes, so employers may be more likely to agree to worker demands.

"It doesn't take many people to tie up an awful lot of capital," Buchanan says.

Risse agrees and says working conditions also play a part, with higher wages potentially reflecting what's called a "compensating factor".

"It's remote work, it's dangerous, it's risky," she says.

But Risse says this explanation only goes so far, as other frontline workers or those in nursing can also face hazardous conditions, and this hasn't bolstered their pay to the same degree.

Another factor to consider is that those working in the mining industry are often FIFO (fly-in, fly-out) workers. When they're on-site, they often work very intensively, which can be seen in their longer-than-average working hours. This could make them eligible for overtime, night shifts, weekend rates or other penalty rates that push up their pay packets.

These factors may also help to explain why those in the electricity industry — who need to be highly skilled and sometimes work in remote areas overseeing large projects — such as power plants and transmission lines, are among the highest-paid.

Highly educated and skilled

Although people working in mining-related industries are among the highest-paid in Australia, they don't top the highest-earning occupations.

Medical practitioners, ICT managers (employees who oversee an organisation's technology systems and infrastructure) and miscellaneous specialist managers top the list. Doctors earn on average $3,554.10 a week, if you include overtime payments, while ICT managers earn $3,401.60 a week.

Many of the professions in the top 10 also worked average or below-average paid hours. The main exceptions to this are medical practitioners, construction, distribution and production managers and air and marine transport professionals.

AI chief economist Greg Jericho says the high rate of pay for some occupations — tertiary education teachers, for example — reflects the level of skill required for the job.

"You can't teach at universities unless you've pretty much got a PhD," he says.

"It is not something where you are quickly replaceable by another person.

"Generally, the more skilled you are or [the more] skills required for a job, the harder it is always going to be to find people who can do that job."

The workers getting an unfair deal

Buchanan says wage differences between skilled and unskilled jobs have remained remarkably stable for centuries, but the big change Australia has seen in the last 15 years has been the decline in public sector pay.

"Teachers and nurses have taken a big hit, and public sector doctors [have been] affected by public sector wage caps [particularly in NSW and Queensland]," he says.

He points to psychiatrists working in the public sector, who are relied on to assess those with mental health issues in the criminal justice system, but whose wages are capped. Buchanan says this can have a disincentivising effect.

"They could make double or triple their money by looking after the 'worried well' [in the private sector]. That's not a good incentive structure to have in your society," Buchanan says.

We should actually be saying, if you are looking after people who are putting our society at risk, technically you're actually performing a more important social function in my view, but that's not the way the labour market's working.

Another anomaly in the wages system is that women doing similar types of work to men are still underpaid.

Even among medical practitioners, there are inequities. The ordinary average earnings for men is $96.20 an hour, while women earn $77.30 an hour.

Risse points out that many of the higher-paid industries are also traditionally male-dominated, and those at the bottom are female-dominated or disproportionately represented by low-skilled or unskilled migrants.

"[Wages are] also a reflection of society-wide dynamics [around] what type of work is considered relatively more important and the way in which pay reflects status and power in society as well."

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.