"One thing that I really like about the Spanish," my friend John Hemingway wrote in a recent blog post, upon his return to Montreal from Madrid, is that when they get fed up with something, usually having to do with their government (local or national), they protest. And when that doesn’t work ... they riot. ... [W]hy aren’t people in the USA taking to the streets in the towns and cities that have filed for bankruptcy? Why aren’t [they] as mad as hell and burning cars and trash cans like their cousins in Spain?"

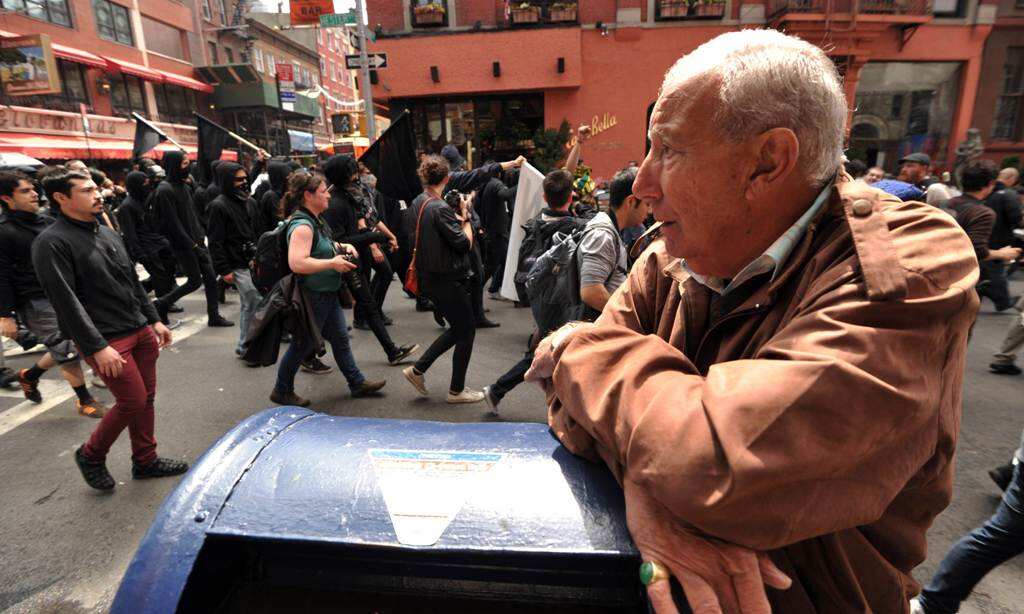

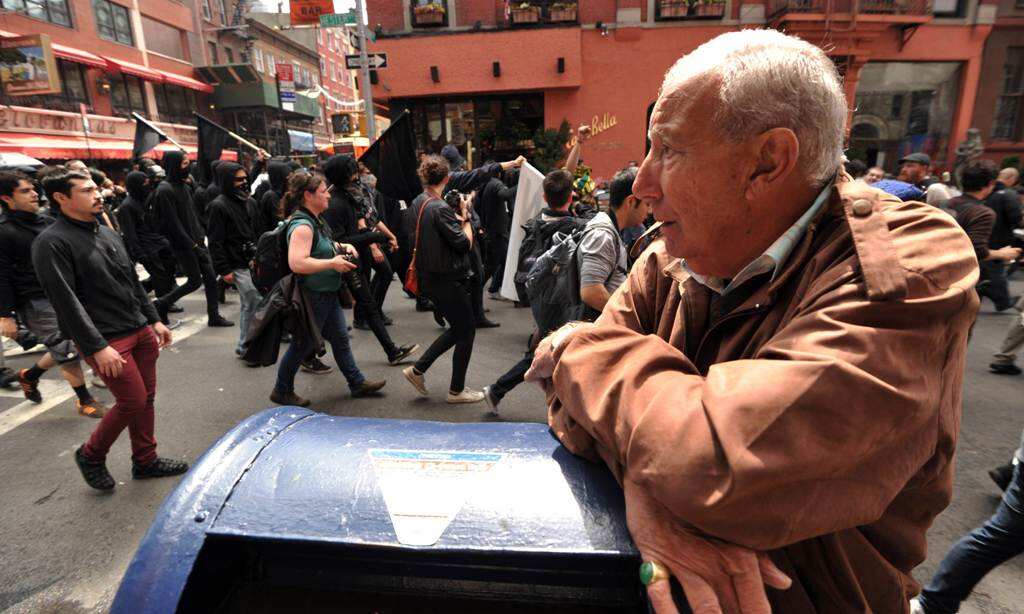

As someone who has covered a number rallies and riots over the past two years, primarily in Spain and Russia, I could certainly see where he was coming from. When the news seems to be one unending reel of protest footage from any number of countries—Ukraine being only the most recent example—it is very easy to wonder why, faced with deep systemic problems of our own, we are not reacting with similar gusto. It is easy to get swept up in the romance of revolution: the mainstream media's breathless, often overly simplistic coverage of such events is testament to that fact.

To do so, however, is to make a couple of closely related assumptions, neither of which necessarily hold up under scrutiny. The first is that mass protest in its various forms—rallies, riots, occupations—is the most effective way of effecting change in our particular circumstances. The second is that the absence of such actions on our streets indicates the absence of any action at all.

The reasons for these assumptions are obvious enough. Mass protest is both highly visible and highly romantic—indeed, it's highly visible precisely because it's highly romantic—and as such has come to define the terms in which we tend to think of progressive action. Sous les paves, la plage, and all that.

There is something to be said for the first of these characteristics and not a hell of a lot to be said for the second. There are undoubtedly circumstances—especially at the birth of a movement—when high visibility is necessary to get one's message out and to lay a foundation for the harder work of coalition- and institution-building, political development and base expansion that is integral to forming an opposition movement that can remain viable in the long run. The problem is that this work all too rarely begins: the romantic fervour and ideological intransigence of the moment tend to bring with them a certain revolution-or-bust mentality that mistakes the protest or occupation itself for the work that needs to be done and gauges the success of an action less on its ability to effect change than on its ability to simply keep going or maintain its numbers. Romanticising mass protest also tends to blind us to its other, rather more important shortcomings. While it is easy to watch events unfold in Kiev and raise a Molotov cocktail in a toast of solidarity with the protesters, it is nevertheless worth remembering that the present situation was to large extent brought about by the failure of the last such uprising there. The inability of the Orange Revolution's leaders to sort their shit out in the wake of their victory in 2004 is precisely what helped to return Viktor Yanukovych to office, legitimately, in 2010. What we are perhaps beginning to see in Ukraine is a cycle in which uprisings lead only to more uprisings and never to lasting systemic change. (I guess we'll see what happens in 2024.) It is also worth pointing out that the current violence in Kiev is reportedly being spearheaded by a far-right nationalist group, Pravy Sektor, which has little time for the pro-EU sentiments that originally brought thousands into the streets. Indeed, liberals tend not to fare very well in revolutionary situations, which are better-suited to more organised, ideologically stringent and, ultimately, methodologically ruthless groups. It is for this reason that protests—from Moscow's Pushkin Square to New York's Zuccotti Park—have a self-defeating tendency to scare away moderates and other potential converts to their cause.

Romanticising mass protest also tends to blind us to its other, rather more important shortcomings. While it is easy to watch events unfold in Kiev and raise a Molotov cocktail in a toast of solidarity with the protesters, it is nevertheless worth remembering that the present situation was to large extent brought about by the failure of the last such uprising there. The inability of the Orange Revolution's leaders to sort their shit out in the wake of their victory in 2004 is precisely what helped to return Viktor Yanukovych to office, legitimately, in 2010. What we are perhaps beginning to see in Ukraine is a cycle in which uprisings lead only to more uprisings and never to lasting systemic change. (I guess we'll see what happens in 2024.) It is also worth pointing out that the current violence in Kiev is reportedly being spearheaded by a far-right nationalist group, Pravy Sektor, which has little time for the pro-EU sentiments that originally brought thousands into the streets. Indeed, liberals tend not to fare very well in revolutionary situations, which are better-suited to more organised, ideologically stringent and, ultimately, methodologically ruthless groups. It is for this reason that protests—from Moscow's Pushkin Square to New York's Zuccotti Park—have a self-defeating tendency to scare away moderates and other potential converts to their cause.

The argument that the Occupy movement failed, pushed by those with a vested interest in having us believe it to be true, is based to large extent on the rather pedestrian fact that the tents eventually had to come down. In fact, Occupy's greatest successes have all taken place since the occupations themselves disbanded or, more commonly, were forcibly removed. This is the most pertinent riposte to the suggestion that mass protest remains the most effective method available to activists, at least in our present circumstances, and also puts paid to the idea that nothing is being done to fight wealth inequality simply because nothing is happening in the streets. I spoke to Occupy.com's Carl Gibson about what has been going on since the physical encampments that first brought the movement to prominence were taken down nearly two years ago. He cited a number of initiatives, from getting fast food workers to strike for better wages to programs that are helping to build homes for the homeless, as examples of how the movement has set about actually getting things done after its earlier, headier days in the park. He also cited the work of Occupy's Strike Debt group, which by last November had abolished $14,734,569.87 of personal debt, which it bought for only $400,000.

"They do like debt collectors do," Gibson told me. "They buy up debt for pennies on the dollar and abolish that debt instead of moving to collect the full amount for profit." Small-scale alt-institutions, mutual aid programs and inch-by-inch actions are more reform-minded than revolutionary and are arguably more productive than the original occupations for precisely that reason. For some, however, this is counts as a point against them, just as the establishment of political parties and campaigns, such as Partido X in Spain or Alexei Navalny's campaign to become mayor of Moscow, is seen by some within the relevant movements as a capitulation to the system rather than as necessary steps towards changing it. This is ideological purity at its most self-defeating and potentially damaging: better not to help anyone than to help them in a way that concedes some ground to one's opponents. Gibson, too, is unequivocal on this point.

Small-scale alt-institutions, mutual aid programs and inch-by-inch actions are more reform-minded than revolutionary and are arguably more productive than the original occupations for precisely that reason. For some, however, this is counts as a point against them, just as the establishment of political parties and campaigns, such as Partido X in Spain or Alexei Navalny's campaign to become mayor of Moscow, is seen by some within the relevant movements as a capitulation to the system rather than as necessary steps towards changing it. This is ideological purity at its most self-defeating and potentially damaging: better not to help anyone than to help them in a way that concedes some ground to one's opponents. Gibson, too, is unequivocal on this point.

"Last century's tactics have played themselves out," he says. "People need to be aware that the next phase of the movement is solution-oriented. It's one thing to point fingers and call people out. That's important, but we've been doing that for awhile now, and nobody is taking us seriously because when they ask, 'So what are you doing about it?' we never have an answer."

"That's where mutual aid comes in," he says. "Abolishing millions of dollars in distressed medical debt helps your community a lot more than camping out in a park or holding a sign or e-mailing a petition. That's honest-to-god action."

"The goal is to listen to the community's needs, work to meet those needs outside of the existing political system, and to meet the needs that must be met from within the system by running our own candidates for local office, who pledge to refuse any corporate funding, so they'll be serving the people instead of themselves."

"The goal is to actually help people even as we're making our point."

Gibson may not be "burning cars and trash cans like [his] cousins in Spain," to use John Hemingway's words. But he's certainly "as mad as hell," and he's doing something about it. The fact that many remain unaware of this is telling. Happy to support protest and revolutionary action when it is taking place against our perceived rivals and enemies overseas, readily ignoring ideological peccadilloes where they exist in favour of simplistic and often false dichotomies, the mainstream media is quick to demonise such action when it takes place at home. A Molotov cocktail thrown in Kiev or Moscow is thrown by a freedom fighter or democrat, even when the democrat in question is actually a hardline nationalist or a neo-Stalinist. A Molotov cocktail thrown in Portland or Oakland is thrown by an anti-social provocateur. It's not hard for the media to peddle this double-standard, to speak of domestic protesters the way that authoritarian governments speak of theirs: occupations and mass protests, let alone riots with their attendant destruction, are a god-send to those who wish to discredit them, containing within them the seeds of their own bad press. They also have a tendency to fade out in such a way—one cannot occupy a park indefinitely—that allows one to put forward the specious argument that the cause of the grievance has disappeared, too. It is much harder to demonise a group of people who are building homes for the homeless or raising funds to alleviate debt. No dirty hippies to point to here. No anti-social elements to be seen. Better not to speak of them at all. People might start getting ideas.

Matthew Clayfield is a freelance foreign correspondent who covered the 2012 Russian presidential election from Moscow.

Share