As property prices across Australia continue to rise, many aspiring homeowners have their hopes pinned on what has become the mantra of housing affordability — increasing supply.

Governments across the country have been working to deliver 1.2 million new well-located homes over five years as one way of unlocking quality, affordable housing.

Council decisions to allow for larger developments in certain areas, such as Sydney's inner-west, have been welcomed by some young people who are showing up to meetings and standing against opposition to increased density, which has slowed approvals in some areas and been a barrier to delivering more homes.

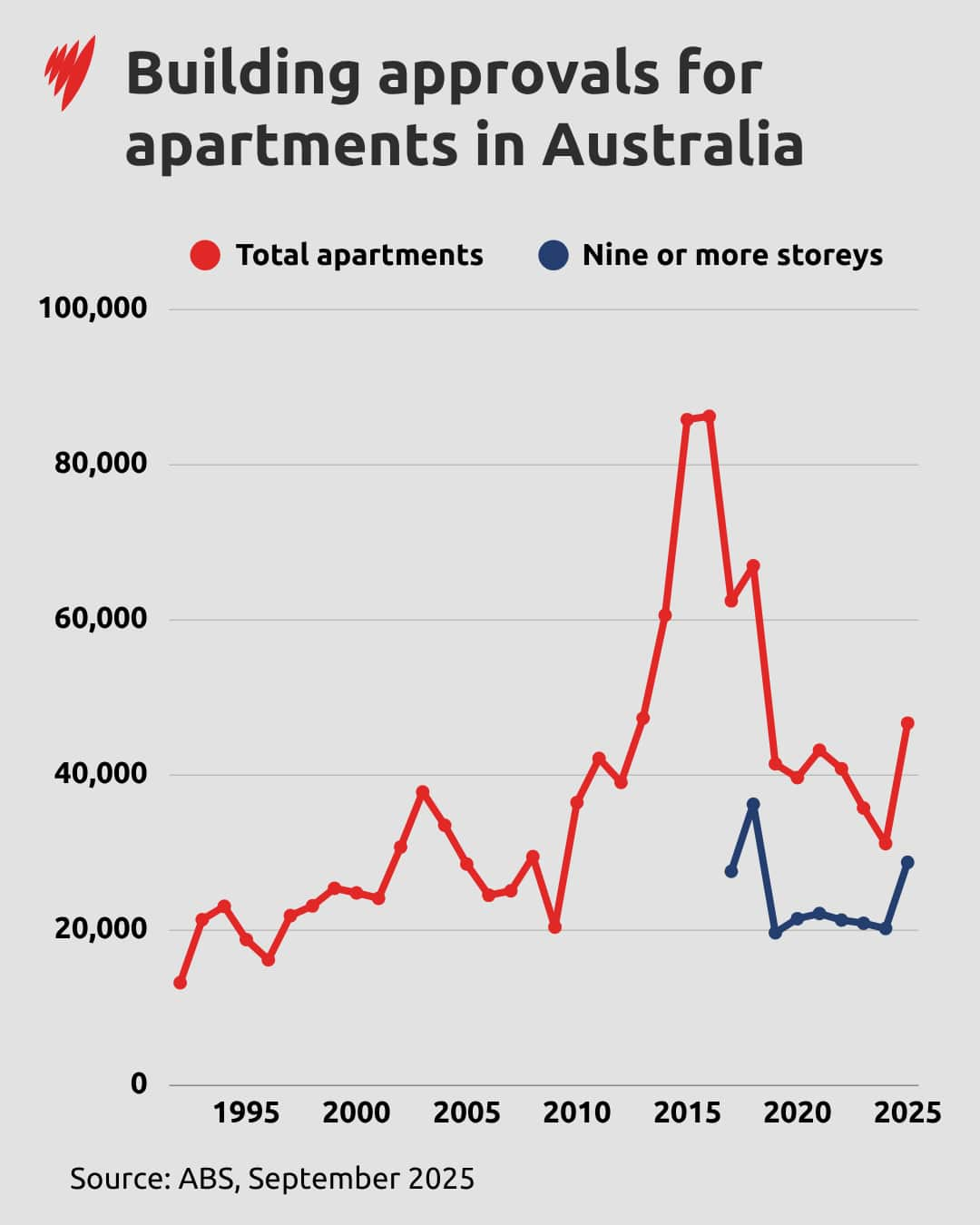

Figures released this week showed apartment approvals have hit a near three-year high. Australian Bureau of Statistics data shows 5,430 apartment dwellings were approved in September, the highest number since December 2022.

Apartment building approvals are on the rise, including for blocks of more than nine storeys. Source: SBS News

Speaking with SBS News last month, an attendee of an Inner West Council meeting said: "I do not believe handing over vast swathes of land to private property developers and investors is the way to solve the housing affordability crisis."

"Private property developers don't exist to create affordable housing — they exist to create profit for their shareholders."

So, will building more apartments bring down prices?

Rezoning impacts housing affordability

When the City of Sydney council was deliberating over the Green Square redevelopment in the 1990s — which involved the construction of a new train station and rezoning of areas from industrial uses to mixed-use — concerns were raised about the plan's impact on housing affordability.

Authorities were concerned because rezoning generally increases the value of land. A 2012 report on the Green Square Affordable Housing Program noted this upward pressure on property values "would raise purchase and private rental accommodation costs beyond the reach of low to moderate income households".

Since its rezoning in 1999, 179 apartment buildings have been constructed in the Green Square urban renewal area, ranging in size from three to 29 storeys.

The Green Square urban renewal area in Sydney, in which the suburbs of Alexandria, Beaconsfield, Waterloo, Zetland and Rosebery were rezoned from industrial to mixed-use and 179 apartment blocks built, is one of the biggest urban renewal projects in Australia. Source: SBS News

Census data indicated the proportion of households with a gross yearly income of $50,000 rose from 15.1 per cent in 1991, to 21.6 per cent in 1996.

Median rents had also increased by $25 per week in just one year, from $195 (in June 1997) to $220 in June the next year. In comparison, rents in Greater Sydney had only increased by $10 (from $200 to $210) and the median rent was lower than in those five suburbs, despite originally being marginally higher.

To address this, the council developed a policy to ensure around 330 units would remain under the ownership of a community housing provider for low to moderate-income households. Developers are now required to set aside 3 per cent of residential development as affordable housing or to provide a monetary contribution towards this.

A spokesperson for the City of Sydney told SBS News that 254 affordable housing units have been built in the area, with another 500 approved.

These units are rented out to eligible households for around 30 per cent of the household's income.

City West Housing, which manages the affordable housing program, generally restricts eligibility to households with a gross income of less than $138,000, although other factors, such as links to the area, can be taken into account.

Affordable housing differs from social housing, which is government-subsidised long-term housing for people on very low incomes.

"Social housing is the sole responsibility of the state and federal governments and is not an area the City of Sydney has remit over," the spokesperson says.

Apartments are not always affordable

Deborah Nixon, a former Redfern resident, says she was lucky to buy a one-bedroom apartment in Waterloo during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Her apartment is across the road from Green Square town centre and this has allowed her to stay close to the city. But she says the unit is not particularly affordable.

For the people that really need housing, I don't think they'd find it here.

Waterloo homeowner Deborah Nixon lives close to Zetland and finds it very convenient, although she would like to see more green space. Source: SBS News

"If we take affordable housing as housing which is affordable to people on low or very low incomes, it won't make a lick of difference because all it does is stop it getting more unaffordable," Davies says.

People that are priced out, won't be priced in.

He says no one would call areas such as Mascot and Green Square (in Sydney), or Docklands (in Melbourne) 'affordable' despite being areas where large amounts of new apartments have been built.

"They're just less expensive than areas like Potts Point [in Sydney]."

Many apartment blocks have been built in Docklands, Melbourne. Source: AAP / James Ross

Since 2006, the population of Zetland in Sydney has grown by almost 400 per cent, according to the latest Census in 2021, increasing from 2,614 to 12,622 people in 15 years.

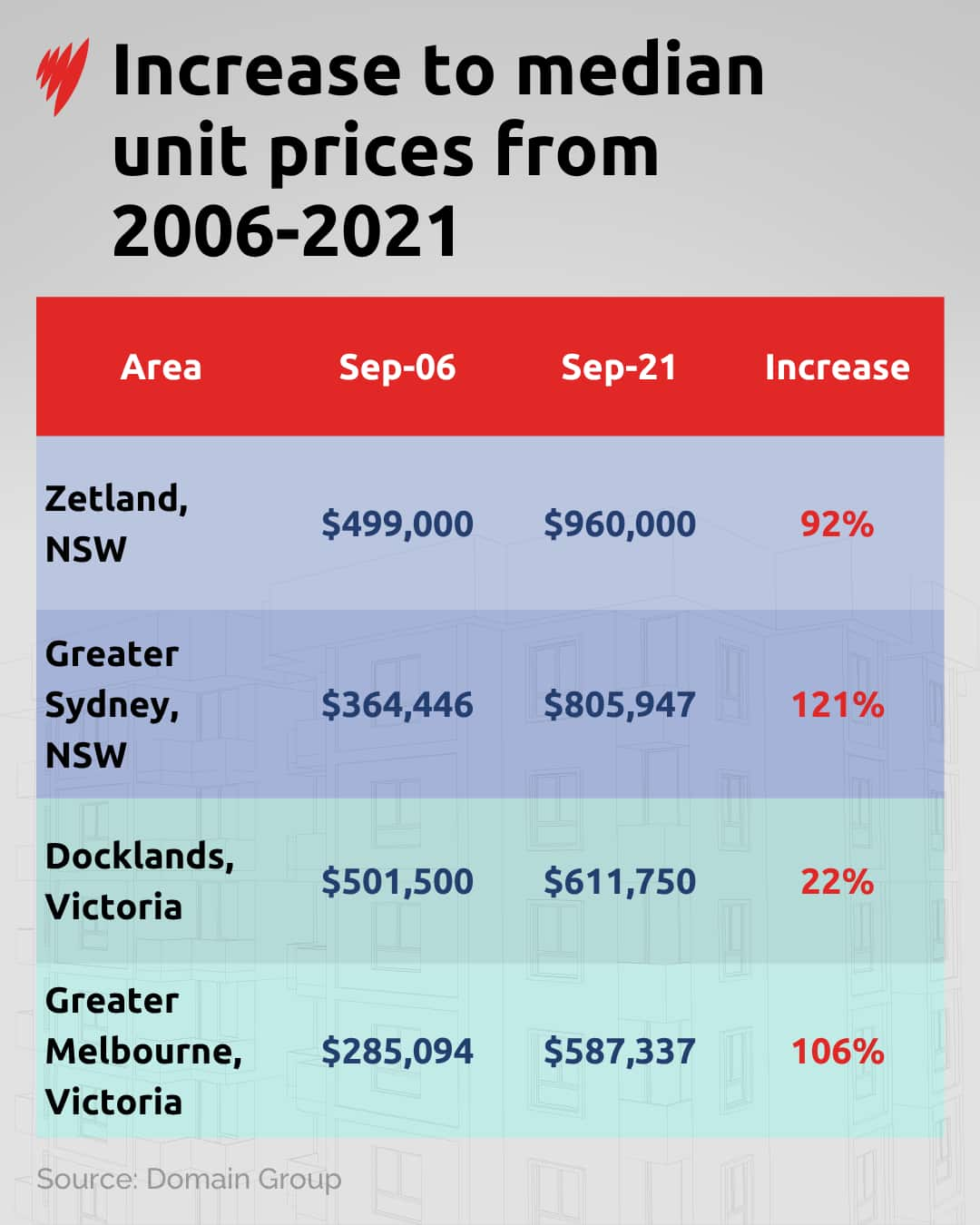

Unit prices in Zetland during the same time period have also grown by 92 per cent, rising from a median price of $499,000 in September 2006 to $960,000 in September 2021, according to Domain.

Median unit prices grew more slowly in areas with large amounts of apartments such as Zetland, when compared to the broader Sydney area. The same happened in Docklands compared to greater Melbourne. Source: SBS News

But the median unit price in Zetland is still higher than Sydney's overall ($805,947).

Supply doesn't equal affordability, but it can help

Davies says one of the reasons we can't rely on the construction of more apartments to deliver affordable housing is that developers are less inclined to build when prices are going down.

Banks will also reduce lending in urban areas with price declines because they don't want to be left with bad mortgages.

But KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley says the average dwelling price in a desirable suburb like Newtown in Sydney might come down because new apartments will be cheaper than the terrace houses already there.

"[Although] it's not necessarily cheap enough for your hospitality workers or lower-income workers to afford those properties," he says.

Rawnsley notes that apartments can also help provide a better mix of housing options, which may also help those on lower incomes.

Building better housing for high-income earners, he says, means they'll shift to the higher quality option and leave the cheaper homes for lower-income earners.

He points out that in gentrifying areas, run-down terrace houses that may previously have been a sharehouse for three or four people have been renovated and turned into family homes.

In gentrifying areas, terrace houses that used to be home to many young renters have been renovated, making them unaffordable. Source: AAP / Bianca De Marchi

If the market had provided more apartments and townhouses, this would have prevented some people from being squeezed out at the bottom end of the market, Rawnsley notes.

Apartments don't necessarily help families

The picture can be more complicated for families.

Davies says if large numbers of houses are demolished and redeveloped into townhouses or flats, prices for houses often rise significantly because they become rarer.

This has implications for families who want dwellings with at least three bedrooms, as developers often don't build large multi-bedroom apartments suitable for families.

You're increasing the supply of two-bedroom dwellings [through the construction of apartments] and maintaining those prices reasonably stably or at least halting the increases — but you're reducing the supply of three-bedroom dwellings.

Domain revealed last year that prices for three-bedroom units had risen faster than for two-bedroom units.

The median price for a three-bedroom unit in Sydney is now higher than a three-bedroom house, partly because units are often more centrally located.

Davies says knocking down houses to build two-bedroom units means you'll probably see fewer families living in a certain area, and more renters.

What this means is you can have a more rotational population — people aren't going to be living there for the long haul.

He says more thought needs to be put into what Australians want their communities to look like.

"I think we need to have stricter or more rigid standards on how many of these apartments should be three-bedroom or more, to encourage more family housing," he says.

Davies would also like to see better minimum design standards in most states.

"[Areas] always change, but we should be guided by how we want areas to change and be intentional about that."

He says building more mid-rise, almost Parisian-style apartments of around five storeys may be more desirable than high rises.

Buildings on the Rue de Rivoli, which runs through the centre of Paris. Source: Getty / Delmarty J/Alpaca/Andia/Universal Images Group

It says allowing three-storey townhouses and apartments on all residential land in capital cities could lift housing construction across Australia by up to 67,000 homes a year. Over a decade this could cut rents by 12 per cent and reduce the cost of a median-priced home by $100,000.

Supply needed at every level, experts say

But Davies says if the aim is to provide affordable housing for low-income earners, this is best achieved if it is built intentionally and that usually means government involvement.

As part of the National Housing Accord, federal, state and territory governments have agreed to build or incentivise the construction of up to 20,000 affordable homes.

This makes up just 1.7 per cent of the 1.2 million homes to be delivered over five years.

But Housing Minister Clare O’Neil says in total the government will deliver 55,000 new social and affordable homes by 2029.

"We’ve got more than 25,000 social and affordable homes in planning or construction with over 5,000 social and affordable homes completed," she tells SBS.

Federal Minister for Housing Clare O’Neil says more than 5,000 social and affordable homes have been built in the past two years. Source: AAP / Joel Carrett

Just 567 homes have been built so far through the HAFF program.

Greens senator Barbara Pocock has questioned why the government isn't directly funding public and community housing.

"It's faster, cheaper, and it worked the last time Australia faced a housing crisis in the post-war years. We know we can do it. We've done it before."

Fotheringham says if Australia is serious about improving affordability, it would also require every development over a certain size to include a certain number of units at an affordable rent level.

"That's common practice in several other countries or jurisdictions," he says.

"It's part of the fabric of London and has been for a long time."

In response to community concern, the Inner West Council has adopted the City of Sydney's inclusionary zoning policy, which requires a 3 per cent affordable housing contribution in upzoned areas. Fotheringham says other neighbouring areas need to do the same.

"It just falls apart because some councils are willing to say 'don't worry about it' and then nothing happens," he says.

We should have it consistent across the country.

Rawnsley points out that calculating what's affordable can also be complicated.

Affordable rents in Green Square are calculated using household income but some schemes use discounted market rent — calculated around 80 per cent of market value — which means rents can still be high in popular inner city areas.

Income caps for certain schemes can also squeeze out families earning slightly more than the threshold.

For example, affordable housing may help someone earning under $60,000 to find accommodation, but someone earning $80,000 may then struggle to compete with those on high incomes for the remaining properties.

If someone on $100,000 can't find good options within their price range, they will apply for other cheaper properties that may have otherwise been affordable to those on $80,000.

"I think the current approach of trying to go more public housing, more social housing, more affordable housing and more private sector housing is best. You've got to put supply into all those markets," Rawnsley says.

"The scale of the problem is so big you need to be doing all these different actions."

Share