It was the 1970s, the peak of the Aboriginal land and civil rights movement, when Professor Fred Hollows received a grant through the Royal Australian College of Ophthalmology to go and look at eye health in remote and rural Australian communities.

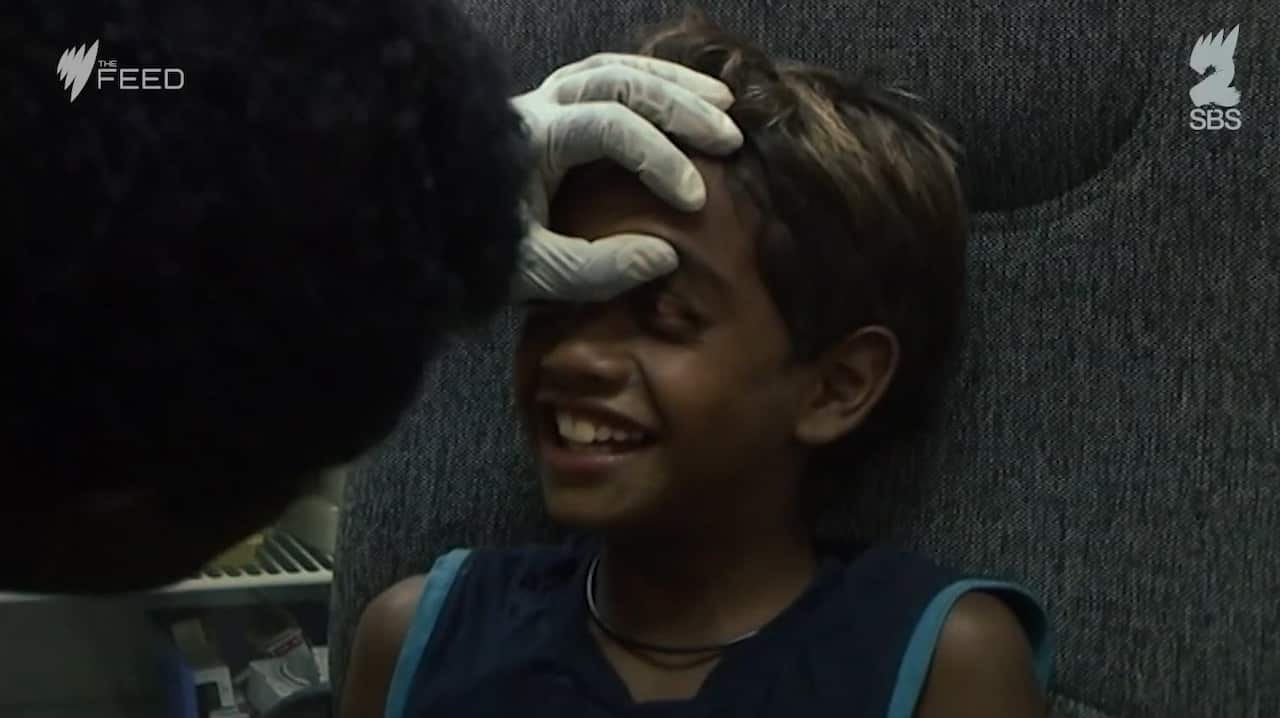

The program took years, with Hollows leading a permanent team of eye health workers thousands of miles around the country.

"Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were still seen as second class citizens in Australia," says psychologist Melanie Jones.

"So for a white guy from Sydney to want to go out and take a team to do something about Aboriginal health, it was just amazing for his time."

That was almost 40 years ago, with a group of people close to Hollows' and who worked on his original team returning to the locations they visited some 23 years after he passed away.

Yet the fight is far from over, with Australia still the only developed country in the world where trachoma is still a problem.

"What can we learn from Fred Hollows that might help us with the current situation?" asked Brian Doolan, CEO, Fred Hollows Foundation

"If anything, it's around engagement: putting the tools in the hands of Aboriginal people to make the difference."

One of these key people is Doctor Kris Rallah-Baker, ophthalmology registrar from the Biri-Gubba-Juru/Yuggera people and the man set to be Australia's first Indigenous eye doctor.

"I went into medicine with the hope I could help other people, but for me it seemed like an impossible dream," he said.

"When my school careers councillor advised me that perhaps I shouldn't do medicine, the reason was because Aboriginal doctors were virtually unheard of.

"I think we had five in the whole country.

"The ultimate goal for him (Hollows), I imagine, was to have an Aboriginal person as an ophthalmologist."

Jones agreed, stating: "It's Aboriginal health in Aboriginal hands."