In the home of former war crimes prosecutor Graham Blewitt, a striking artwork offers a glimpse into the atrocities the retired Sydney-based lawyer has helped investigate.

The piece hanging in Blewitt's home office shows a framed map of Bosnia and Herzegovina, painted over with gravestones marking the location of war crimes and a genocide, which he prosecuted in the 1990s.

Barbed wire lines the border: a symbol of the concentration camps there that shocked the world.

The paper is stained red for the blood of thousands that were massacred during the Yugoslav Wars.

The work is a glimpse into Blewitt's decade-long tenure as the deputy prosecutor for the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY).

The tribunal was the first to investigate international war crimes after former Nazi leaders were tried at Nuremberg, and Japanese leaders at Tokyo, following World War Two. Its successes helped establish the permanent International Criminal Court (ICC) in 2002.

"It's something I'm very proud of being involved in," Blewitt says.

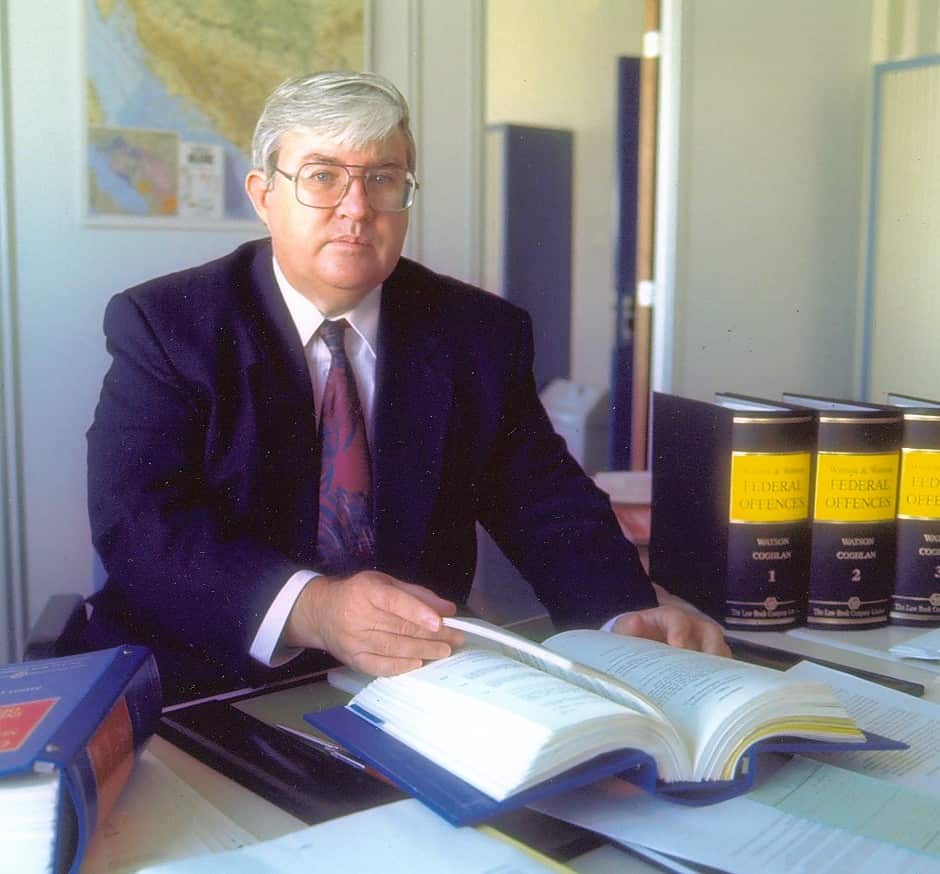

But becoming a pioneer wasn't something the 78-year-old set out to do.

"I got into war crimes accidentally," Blewitt says, recalling how he found himself investigating Nazi collaborators who had come to Australia after World War Two.

After securing his first job in the office of the director of Public Prosecutions, Blewitt says the transition from "ordinary crime" to "war crime" was not that large a leap.

"In many ways, the crimes that constitute war crimes were murders, rapes, ordinary criminal activity, except they were committed in the context of an armed conflict … and on a much larger scale," he says.

After a career spent seeking justice for victims and more than a decade investigating war crimes, Blewitt now finds himself watching others struggle to enforce international criminal law in his footsteps.

What's happening today throughout the world is a complete disappointment.

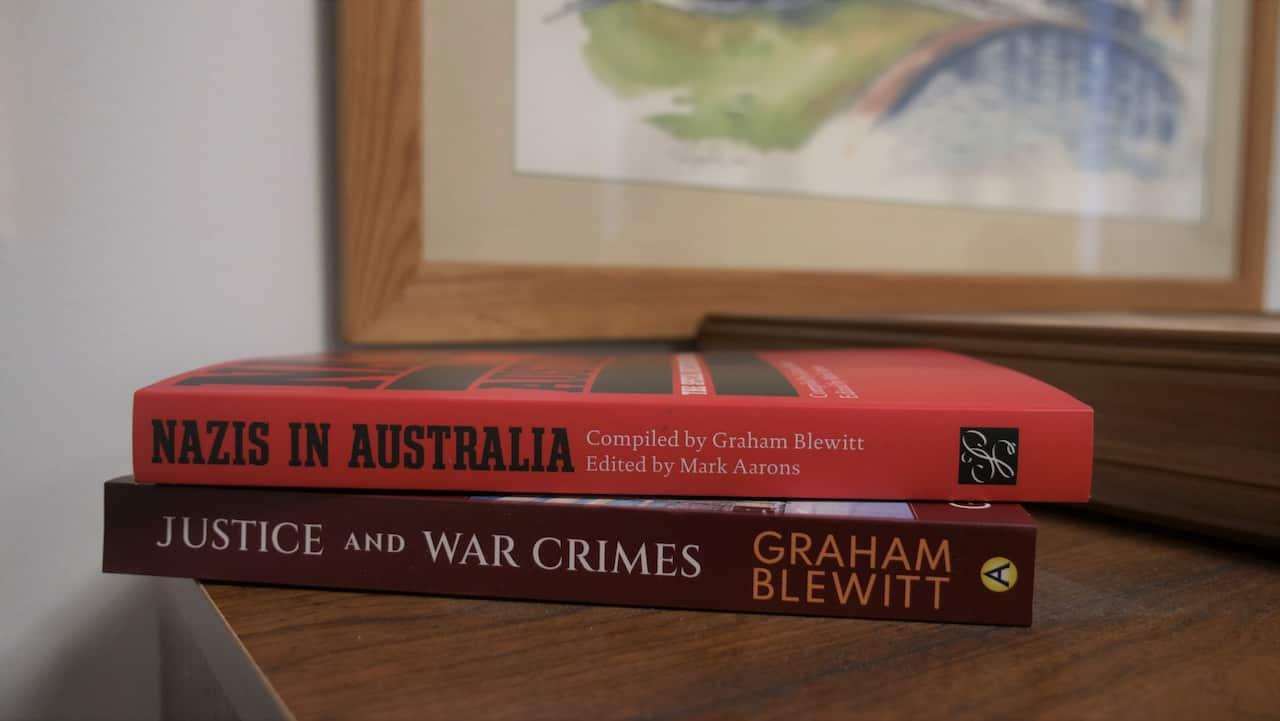

Nazis in Australia

Blewitt started investigating war crimes in 1988, after being recruited to Australia's Special Investigations Unit (SIU) set up by the Hawke government to investigate suspected Nazi collaborators living in Australia.

He became the unit's director in 1991 and investigated Australians accused of being involved in mass executions of the Jewish population, mainly in Ukraine.

This included gathering testimonies from persons in Canada, the United States, Israel and Europe.

We undertook investigations by going to those areas, interviewing survivors, interviewing witnesses who were still there and those who had become refugees after the war.

More than 500 people in Australia were investigated, but many had already died, others died during the course of investigations, and many allegations couldn't be substantiated due to a lack of available evidence.

In the end, three people were charged under Australia's War Crimes Act 1945: Ivan Polyukhovich, Heinrich Wagner, and Mikolay Berezovsky.

Polyukhovich was accused of helping massacre more than 850 Jews in the northern Ukrainian village of Serniki.

Next, Blewitt says, came a world first.

"We sent forensic teams [to Ukraine] and exhumed bodies in the mass graves from the 1940s," he says.

"None of the other units throughout the world investigating war crimes, including the United States, Canada, England, Scotland and Germany, had ever undertaken a mass grave exhumation.

"But we did, and the forensic evidence was overwhelming. It corroborated the evidence of the witnesses that we had found."

Although none of the prosecutions resulted in convictions, Blewitt says the forensic evidence was not challenged.

Polyukhovich stood trial in South Australia but was acquitted by a jury.

Charges against Wagner were withdrawn due to his health, and there was not enough evidence to take Berezovsky to trial.

The work of the SIU was wrapped up in 1992, and the unit then transitioned into the War Crimes Prosecution Support Unit, which was also dismantled in 1994.

Despite its discontinuation, Blewitt says, the SIU's work was groundbreaking in the field of war crimes investigations.

"It was an important piece of work for Australian legal history and it also gave me the confidence and the experience that I could apply when I got to The Hague later on," he says.

Setting up the war crimes tribunal

Blewitt was still working for the SIU when Yugoslavia started to collapse in the early 1990s.

The former socialist bloc included the republics of Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia (now Republic of North Macedonia), Montenegro, and the autonomous regions of Kosovo and Vojvodina.

When some declared independence, a series of violent ethnic conflicts broke out.

"There were daily news reports on the radio, on the TV, in newspapers and it was fairly obvious that there were war crimes being committed," Blewitt says.

In 1992, the United Nations Security Council voted to establish a tribunal, the ICTY, to investigate. Blewitt took on the role of deputy prosecutor in February 1994.

He arrived in The Hague to find himself entirely in charge of building the office from scratch, recruiting staff and commencing investigations

Its first prosecutor, Richard Goldstone, was appointed in August after being released from the constitutional court in South Africa by Nelson Mandela.

Prosecuting a genocide

In July 1995, Blewitt's desk was already piled high with reports of atrocities throughout the Balkans: mass killings of unarmed civilians, widespread detentions in concentration camps, torture, and rape.

But he remembers hearing reports "something terrible" had happened in Srebrenica, a small town in the far east of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

It would turn out to be the largest mass killing on European soil since World War Two, and was later determined to be a genocide by the ICTY and the International Court of Justice.

More than 8,000 mostly Muslim men and boys were slaughtered in what had been designated a United Nations 'safe zone'.

Blewitt says his team "established very early in the piece" that the attack on Srebrenica was carried out by Bosnian Serb forces under the military command of General Ratko Mladić, and leadership of Radovan Karadžić. They set out to indict both.

The investigation soon revealed the existence of mass graves, containing the bodies of thousands of victims who had been executed.

"We were assisted greatly by the Americans who gave us aerial imagery of the mass grave sites," Blewitt says.

"Once the Serbs found out we were aware of the grave sites, they started to remove the bodies and took them to more remote locations to bury them in secondary graves. We were able to identify both the primary grave sites and the secondary sites, and we decided to carry out exhumations of the bodies in those grave sites."

Blewitt says his work ordering exhumations during the Nazi war crimes investigations in Australia was a "major help", as some of the staff involved were now working with him in The Hague.

"Painstakingly, they examined the sites by comparing soil samples," he says.

"They were able to link the secondary sites with the primary sites, and all that forensic evidence became very important in the subsequent prosecutions that took place."

In November 1995, indictments were issued against Karadžić and Mladić, preventing them from attending peace talks in Dayton, Ohio.

Critics told them the decision might interrupt the peace process.

"But our view was that you can't have peace without justice and that they were the primary persons responsible for the genocide, so they had to be prosecuted," Blewitt says.

How to arrest an alleged war criminal

Blewitt recalls the prosecutor's office reaching a point where dozens of public indictments had been issued, but the ICTY was at risk of becoming a "toothless tiger" because none of the people accused of war crimes had been brought to trial.

There was finally a breakthrough in 1996 during the term of the ICTY's second chief prosecutor, Louise Arbour from Canada.

"We were able to effectively force NATO, the [Stabilisation Force in Bosnia and Herzegovina] SFOR, into starting to arrest the fugitives," Blewitt says.

"Once the first arrest attempt took place, it opened up the floodgates."

Before we knew it, the detention centre in The Hague was full and it was necessary to build two additional courtrooms to accommodate all the accused.

It was an exciting and historic moment, which Blewitt says shaped the face of The Hague and international humanitarian law forever.

"Trials were taking place on a daily basis in three courtrooms, the tribunal was well and truly underway," he says.

"[It] gave confidence to those setting up the permanent international court — the ICC — and when that was established, then clearly the legacy of the tribunal had made itself clear."

Alleged war criminal drinks poison in courtroom

The war crimes trials continued long after Blewitt finished his post as ICTY's deputy prosecutor.

It was a chapter that dominated the headlines.

Then Serbian president Slobodan Milošević was the first sitting head of state to be indicted for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. But he was found dead in his cell in The Hague while on trial in 2006.

A post-mortem determined he died of a heart attack.

In 2017, Bosnian-Croat general Slobodan Praljak died after drinking poison in the courtroom.

When the judge dismissed an appeal to overturn his war crimes conviction, Praljak declared "Slobodan Praljak is not a war criminal" before drinking from a small bottle in full view of court cameras.

Former Croatian Serb leader Milan Babic also took his own life in a UN detention centre in 2006. Another Croatian Serb, Slavko Dokmanovic, did the same in 1998.

Karadžić and Mladić were found guilty of war crimes and genocide in 2016 and 2017, respectively.

Both received life sentences and remain in prison in The Hague.

"All 161 individuals indicted by the tribunal were dealt with; either arrested, stood trial, some were convicted, some were acquitted, some died," Blewitt says.

When he left the ICTY in 2004, Blewitt felt "very optimistic that at last international criminal law was enforceable".

"But at this point in time, I don't hold that optimism anymore," he says.

Frustration as world leaders undermine prosecutions

With wars raging around the world, Blewitt has been watching in frustration as some world leaders undermine the institutions set up to hold the perpetrators of war crimes to account.

In February, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order sanctioning the ICC, saying the court had issued "baseless warrants" against Israeli leaders, including Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

It noted the ICC — which relies on the cooperation of its 125 member states to carry out any arrest warrants — had no jurisdiction over either Israel or the US, as neither are parties to the Rome Statute, the treaty which created the court.

The ICC's 'Situation in the State of Palestine' case says it has reasonable grounds to believe Netanyahu and his former defence minister Yoav Gallant bear criminal responsibility for "the war crime of starvation as a method of warfare; and the crimes against humanity of murder, persecution, and other inhumane acts". Israel denies the allegations.

Technically, any member of the ICC is required to arrest Netanyahu if he travels there, although the court has no independent power to enforce warrants. In April, Hungary announced it would withdraw from the ICC before hosting Netanyahu.

Trump's order personally sanctioned the ICC's prosecutor, Karim Khan. The US later imposed sanctions on a further four ICC judges in June, which barred their entry to the US and blocked any property or other interests in the country.

The ICC has condemned Trump's executive order, which it said sought to "harm its independent and impartial judicial work".

Blewitt views Trump's sanctions on the ICC as "an appalling situation" that potentially interferes with the course of justice, and believes many international leaders could be in contempt of court.

Alongside its investigation into Israel, the ICC has also been investigating war crimes and crimes against humanity alleged to have been carried out during the US invasion and occupation of Afghanistan between 2001 and 2021.

Israel accused of war crimes

Gallant described the ICC's push for warrants against him and Netanyahu as an attempt to deny the state of Israel the right to defend itself and ensure the release of hostages.

"The parallel [Karim Khan] has drawn between the Hamas terrorist organisation and the State of Israel is despicable," he said in May.

The ICC issued an arrest warrant for Hamas leader Mohammed Deif for alleged crimes against humanity and war crimes, but the charges were dropped in February after his death.

Netanyahu has repeatedly called the allegations against him "absurd and false".

The ICC's investigation into actions within the Palestinian territories began in 2021, and it has been looking at events going back to 2014. It now includes actions related to the Hamas attack of October 7 2023.

Blewitt points to reports, including in The Guardian, that Israel's intelligence service, Mossad, had allegedly surveilled, hacked, pressured and threatened senior ICC staff in an effort to derail the court's inquiries.

He claims a former colleague involved in the Netanyahu and Gallant indictments had resigned from the ICC due to stress after being advised by police to take security precautions, such as getting a bulletproof front door and windows installed at their home.

It's one thing not to recognise the tribunal, the ICC, but it's another thing to deliberately interfere with the processes.

The Israeli government did not respond to SBS News' request for comment.

The Israeli Prime Minister's office has previously called the allegations about Mossad "false and unfounded".

Claims of genocide

The ICC case has not included the charge of genocide.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ), however, is considering a case brought by South Africa, considering whether Israel is committing genocide in Gaza.

Blewitt says, if he were in the ICC prosecutor's office today, he would have "no hesitation in bringing an indictment against the Israeli leaders for genocide, and let the court decide whether it's genocide or not".

He compares it to Srebrenica, which was at the time deemed a "clear-cut genocide", because there was a "genocidal intent" to "destroy in whole or in part a political, ethnic, or religious group".

Asked why he has this assessment, Blewitt says: "There's no direct evidence apart from comments made by various Israeli leaders from time to time suggesting that they just want to wipe the Palestinians from the face of the Earth."

He says there appears to be a lack of proportionality to the Israeli strikes, which often kill children or innocent civilians.

"They'll bomb a building and say they're after a particular Hamas leader and not worry about the 30, 40, 50, 100 people in close proximity who are killed or injured as a result of that strike," Blewitt says.

Israel has repeatedly denied targeting civilians and has accused Hamas of using civilians as "human shields".

This week, Israeli government spokesperson David Mencer again rejected genocide accusations.

"It is baseless. There is no intent, key for the charge of genocide," Mencer said.

How alleged Gaza war crimes could be investigated

Blewitt says the process of investigating alleged war crimes in Gaza would be very different from his experience in the 1990s, when there was no social media or iPhones.

Now anyone with a phone can record what's happening and there's no end of evidence for those investigating what's happening in Gaza.

"The difference now is that it's not possible for investigators to gain entry to Gaza on the ground or to investigate crime scenes," Blewitt says.

"In 1995, ICTY investigators had access to crime scenes. But right now, those investigating Gaza do not."

The Gaza health ministry says nearly 60,000 people have been killed in Gaza since October 7 2023. It does not distinguish between civilians and combatants.

Blewitt, as a former prosecutor, says if he were in charge now, it would be hard to know where to start, but he would likely begin by looking at the most serious incidents.

He explains the ICC can only bring indictments against Israel's leaders if it can establish that Israel hasn't fully investigated the alleged crimes and held those responsible to account.

No peace without justice

The ICTY's war crimes cases took over a decade to resolve, and the resolution of cases related to current conflicts, such as those in Gaza and Ukraine, could face the same delays.

Blewitt says outcomes may depend on whether the ICC can regain its legitimacy in the face of efforts to undermine it.

"If the ICC can outlast the Trump administration and can regain some credibility, then maybe it'll be back on track," he says.

In recent weeks, international condemnation over Israel's actions in Gaza has grown, particularly in relation to humanitarian aid and the growing hunger crisis.

World leaders, including Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, have rejected Israel's denials that there is "no starvation in Gaza". Even Trump says images of children are "real starvation stuff".

Human rights groups in Israel are also accusing the government of genocide, including prominent activist Yuli Novak of B'Tselem.

While there are undeniable forces working against international criminal justice, Blewitt considers the opportunity to work in the field a "privilege".

"You can't have peace without justice."

— Additional reporting by AFP

If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732, text 0458 737 732, or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au. In an emergency, call 000.

Readers seeking crisis support can ring Lifeline on 13 11 14 or text 0477 13 11 14, the Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467 and Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800 (for young people aged up to 25). More information and support with mental health is available at beyondblue.org.au and on 1300 22 4636.

Embrace Multicultural Mental Health supports people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.