Almost a quarter of a million Australians are estimated to be living with hepatitis B - a disease that kills more than 800,000 people worldwide every year.

But, now, scientists are gathering in Australia with a pledge to fast-track a cure within 10 years.

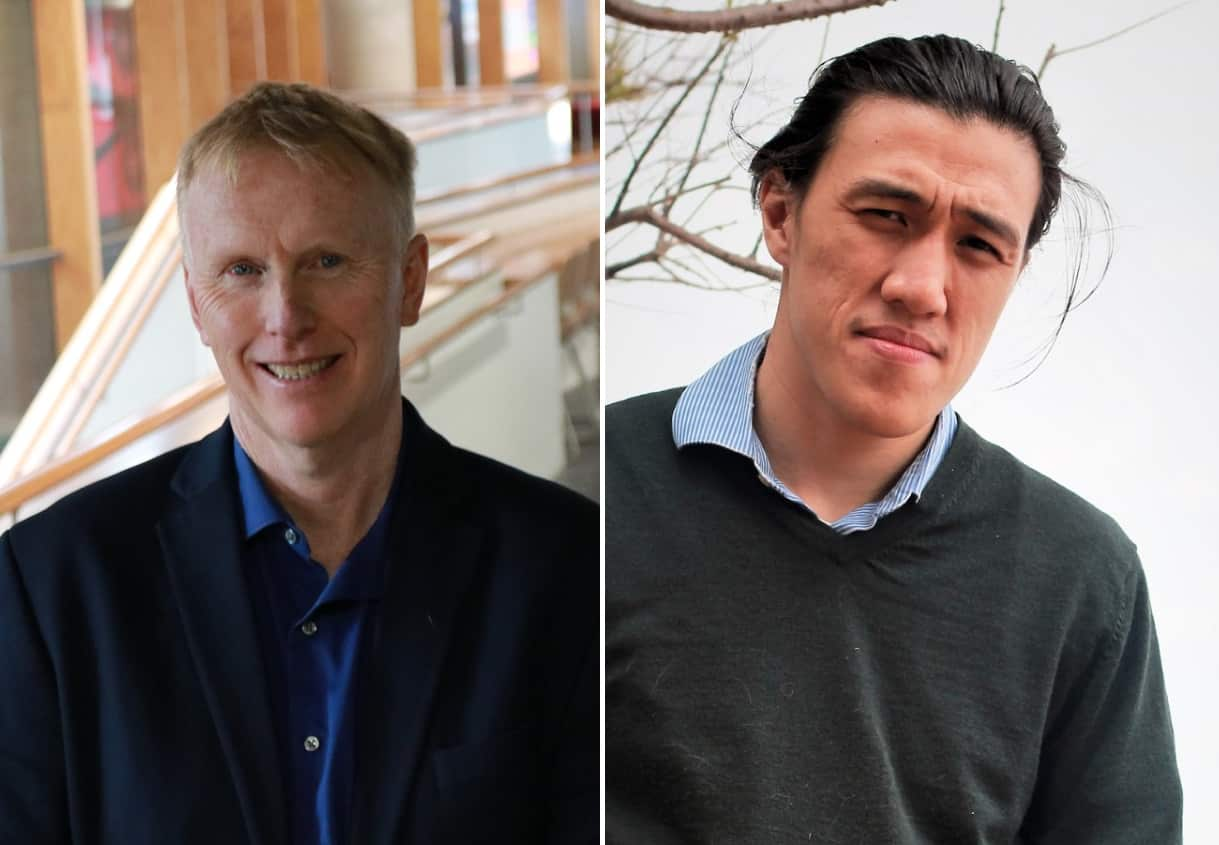

Dr Thomas Tu is a world-renowned hepatitis B researcher who has a very personal motivation to discover more of its secrets.

Nineteen years ago he was diagnosed with the disease.

"Knowing how it feels to have hepatitis B makes me want to prevent that in other people," he said.

"I want to relieve them of this burden. Having hepatitis B really inspired me to do research into it and find ways to cure it and learn how the virus causes disease and possibly prevent it."

The Sydney medical scientist has detected a particular form of the virus that lingers in a chronically ill patient's liver.

This week, he'll present his findings to a meeting of international experts in Melbourne that will commit to fast-tracking a cure within 10 years.

The co-chair of the meeting, Professor Peter Revill, from Melbourne's Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, says curing the disease would be a game-changer.

"We are well along the way," he said.

"There is probably 30 different drugs in the early stages of clinical trial which is very, very exciting but there is a long way to go.

"This is a very very tricky virus. We have 257 million people living with this chronic disease and there is no cure at the moment. It would be so important for these people if we could do that."

In Australia alone, there are some 240,000 patients with the disease - more than HIV and hepatitis C combined.

Researchers are also trying to determine why chronic hepatitis B is four times more prevalent among Indigenous Australians and a major cause of deaths in their communities from associated liver disease and cancer.

Professor Revill says it's unclear why, but it's hoped new research may help find an answer.

"The virus was first known as the Australian antigen and was discovered in 1965 in the serum of an Indigenous Australian," he said.

"It's a terrible statistic. Researchers at the Doherty Institute and Menzies Institute in Darwin have discovered a novel strain of the virus that is only present in Indigenous Australians in the Northern Territory and they think that may have some sort of role."

There's high prevalence among migrants from south-east Asia as well and for Sidney Vo and her son it means facing deportation back to Vietnam.

Despite being in good health and needing no medication, she says the government considers her condition too great a potential burden on the health system.

"I really hope they might change their mind at the last minute because I am not disabled. I am skilful at my job," she said.

The Canberra childcare worker will address the conference this week, with just a fortnight to go until her visa runs out.