The following story contains images some readers may find distressing.

Almost as soon as the Bondi Beach massacre began on Sunday, misinformation and disinformation about the attack spread online, concerning everything from the identity of the perpetrators to conspiracy theories about 'false flag' operations and 'crisis actors'.

Father and son Sajid and Naveed Akram are alleged to have carried out the shooting, which targeted a Hanukkah event, in which 15 people were killed.

Sajid Akram was also killed during a shootout with police, while Naveed remains under police guard in hospital and is expected to be questioned and charged on Wednesday.

False quotes, screenshots, photos and videos have continued to circulate in the days that followed — many of which were used to stoke division and promote racist and antisemitic conspiracy theories.

So what were some of the falsehoods, how did they spread, and what steps can you take to identify misinformation and disinformation shared online?

What are misinformation and disinformation, and how did they spread?

Misinformation is false information that is spread without the intent of misleading others, and is often mistakenly shared by someone who believes the content to be accurate.

Disinformation is deliberately fabricated or misleading information shared by someone to deceive people or sway public opinion.

That can become misinformation if widely distributed without being debunked.

Misinformation and disinformation spread online during and in the aftermath of the Bondi Beach attack through websites and social media, and often utilised artificial intelligence.

This included users circulating falsehoods and doctored photos and footage online, screenshots of fabricated news reports, as well as incorrect claims made by AI chatbots such as Elon Musk's Grok — only backtracking after being challenged on its claims by users.

What were some of the incorrect claims?

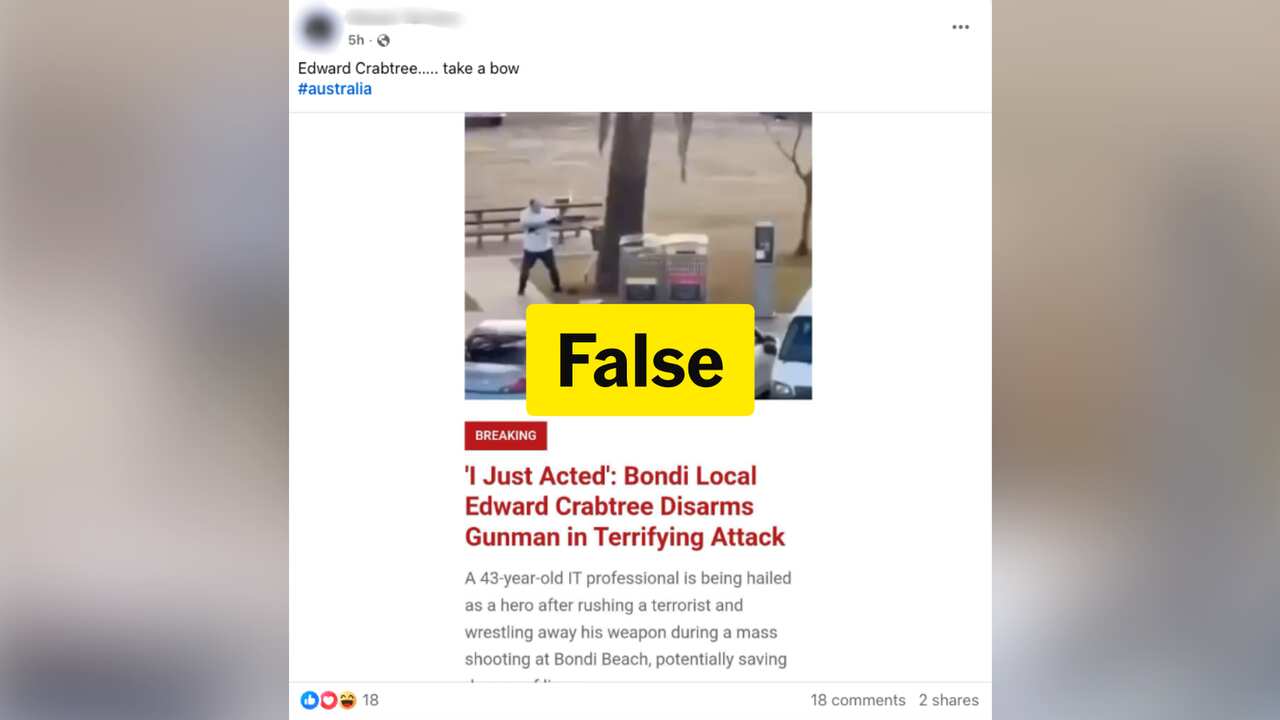

Multiple falsehoods that circulated online included the misidentification of Ahmed Al-Ahmed, a Syrian-born shop owner who disarmed one of the gunmen by wresting a gun out of their hands, and who has been widely hailed a hero.

Australian Associated Press' (AAP) FactCheck service found several social media posts falsely identifying him as a man named Edward Crabtree.

That claim was sourced from a website called The Daily, that 'quoted' Crabtree from an "exclusive" interview given from his bedside in hospital.

A search of the domain found that the website had been set up on the day of the attack, many of the links don't work, and it contains other false information.

Grok, meanwhile, claimed a verified clip of the confrontation was an "old viral video of a man climbing a palm tree in a parking lot, possibly to trim it" and that it may have been staged.

In another instance, Grok misidentified an image of Al-Ahmed as an Israeli hostage who had been held by the Palestinian group Hamas.

Elsewhere, Grok incorrectly described footage from the attack as filmed during Tropical Cyclone Alfred earlier this year.

Disinformation watchdog NewsGuard also reported that in the aftermath of the attack, social media users shared an authentic image of one of the survivors of the attack, falsely claiming he was a 'crisis actor' — a term used by conspiracy theorists to allege someone is feigning injuries or death to deceive people.

AAP's FactCheck service also debunked a photo shared widely on social media of attack victim Arsen Ostrovsky, purporting to show him having fake blood applied before the attack.

The image was used to falsely claim the attack was staged by the government, police and media.

Ostrovsky was grazed by a bullet in the shooting, and gave several TV news interviews at the scene, bandaged and bloodied.

The image shared online exhibited "hallmarks" of AI generation, according to AAP FactCheck.

In an interview Ostrovsky gave on TV, he was clearly seen wearing a shirt that had the words United States and Marines, and a logo of an eagle.

In the fake image that was circulated, the shirt features different (and illegible) text and a different logo.

Elsewhere in the shared image, background vehicles appear to merge together, and multiple people have distorted or missing hands.

AAP FactCheck also debunked multiple false quotes purported to have been said by One Nation leader Pauline Hanson, shared by foreign-run Facebook pages operating from Vietnam.

One web article that was linked to in social media posts falsely quoted Hanson saying Prime Minister Anthony Albanese was a "weak, spineless coward" and that Albanese had called Hanson a "tiny piece of garbage" in a closed-door Labor Party meeting.

There is no evidence that either of the quotes are genuine.

Hanson has not posted those remarks on her social media and there's no other record of them anywhere else online.

There has also been no reporting of a Labor caucus meeting.

The article that was linked to in social media posts has a byline of an apparent "political correspondent", but there is no record of a political journalist working in Australia with the name used.

Other social media posts by the same Facebook page, Swim Aquatics, linked to a story on an external website claiming Hanson said "millions of Muslim citizens in Australia could lose their citizenship" and that she linked the attack to the return of "ISIS brides" to Australia.

The post linked to a website called Amazing Blogs that is predominantly in Italian, and the quotes attributed to Hanson are fake.

Several posts shared online also misidentified the alleged gunmen, or made false claims about them in the wake of the attack.

One Facebook post showed a photo of a man in a Pakistan cricket shirt alongside another image of Naveed Akram, claiming both had carried out the attack.

The man in the cricket shirt was not involved, writing in a post on Facebook that people had been posting his social media images alongside false claims that he was involved in the attack.

"I am completely innocent and have no connection whatsoever to what happened," the man wrote.

Other posts shared pictures of a man they claimed was involved in the shootings called "Khaled al-Nablusi", who was described as a "Muslim migrant" and "Lebanese national of Palestinian descent".

AAP's FactCheck service found images of the man that had previously been shared online with claims his name was "Marquz al-Bunni" and that he was involved in a US Army base shooting in August this year.

The images are photos of a writer published in an online magazine that have been manipulated to add a beard.

Other posts falsely claimed Naveed Akram was an Israeli national named "David Cohen", including a fake screenshot of a Facebook profile.

The profile showed several signs of being AI-generated and does not match the layout, formatting or content or genuine Facebook accounts. There are also several misspellings. Authorities have said Naveed Akram is an Australian-born citizen.

Elsewhere, Facebook users falsely claimed people in Israel and India had been searching the name "Naveed Akram" on Google hours or days before the attack, with purported screenshots of time-series search activity for his name from Google Trends.

The posts were used to claim the attacks were 'false flag' attacks perpetrated by Israel or India.

AAP FactCheck has debunked this. It searched Google Trends and found no results for people searching the term "Naveed Akram" in Israel or in India before Sunday’s attack.

Other posts shared on Instagram falsely claimed Akram served in the Israel Defense Forces — to which he has no reported links.

How can you spot fake information online?

The eSafety Commissioner has advice on how to tell if information, images and videos posted online might be fake.

You should seek out information online from a trustworthy source, such as major national or state media services and government websites.

Ask yourself if quotes make sense or if they appear to miss the wider context, if the content seems believable, and if there is enough evidence and reasoning provided to justify claims or conclusions. Does the information shared expressly promote a political agenda or worldview?

When it comes to visual content shared online, check if photos look real or could have been altered using an app or software. AAP's FactCheck service says to look out for visual inconsistencies, such as distorted hands and limbs, or garbled and unreadable letters and numbers.

You can also do a reverse image search through a platform such as Google Images or TinEye to see if a photo appears elsewhere online with a different name, description or context.

False footage may have blurring, cropped effects or pixelation, or contain glitches, sections of lower quality or changes in the lighting and background.

It might have badly synced or mismatching sound, or irregular blinking and movement that seems unnatural.

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.