Feature

'I stepped over a dead body': Why 2023 could be Mount Everest's worst year yet

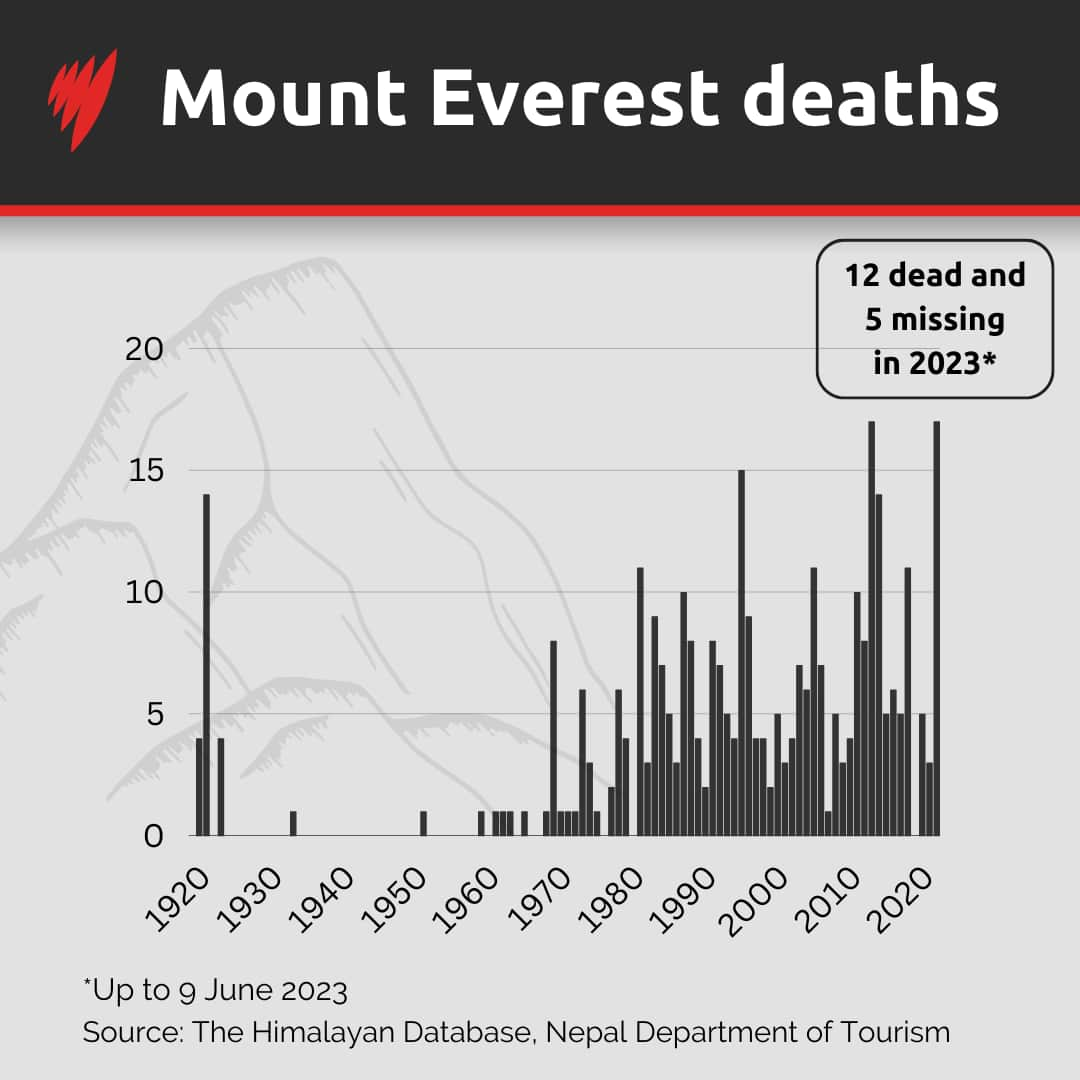

With the number of dead and missing climbers already equalling Mount Everest’s most fatal year on record, some are questioning whether the increasing demand from people wanting to reach its summit is sustainable.

Published

For Melbourne woman Jen Willis, climbing Mount Everest was a dream imagined at a young age.

“When I was about eight, my grandpa had some pictures hung up of mountaineers and some mountaineering books,” she said.

“He gave me a brooch of a mountaineering boot and an ice axe, so that was a treasure that I put away.”

But it wasn’t until she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) that she decided to do something about it.

In April, the 51-year-old mother-of-three set off to Nepal with the intention of becoming the first Australian with MS to summit the world's highest mountain.

“My mental mantra to myself at one point was, ‘just keep your eye on the prize, Jen’, focus and keep going,” she said.

But while she knew the risks, she didn’t expect to be faced with the grim reality of death on the mountain.

“As we were heading up from Camp 3 to Camp 4 there was a sherpa who had passed away,” she said, referring to one of the guides who support climbers.

“That was incredibly confronting.”

The body was lying across the ropes climbers are attached to and Willis said she had no choice but to step over it.

“To continue climbing was a matter of having to move around where he was deceased on the rope,” she said.

“That moment, for me, there was definitely a question in my mind – ‘do I continue climbing or is this the moment I would turn around and go back down?’ Not so much out of fear, but there’s no way in Australia that I would walk past someone that was very unwell or deceased and continue my journey.”

Willis, who has just returned to Australia, made it to 8,000 metres but was unable to complete her dream of reaching Mount Everest's summit of 8,849 metres.

“I guess that prize wasn’t necessarily summiting, [it was] showing up each day, taking myself higher and higher,” she said.

Australian man Jason Kennison was among those who died on the mountain this year. The 40-year-old had re-learnt to walk after a road accident and made it to the summit, but he died on the way back down after becoming unresponsive at 8,400 metres.

The number of people climbing Mount Everest has increased over the years but Yubaraj Khatiwada, the director of Nepal's Department of Tourism, blames the high number of fatalities this year on poor weather.

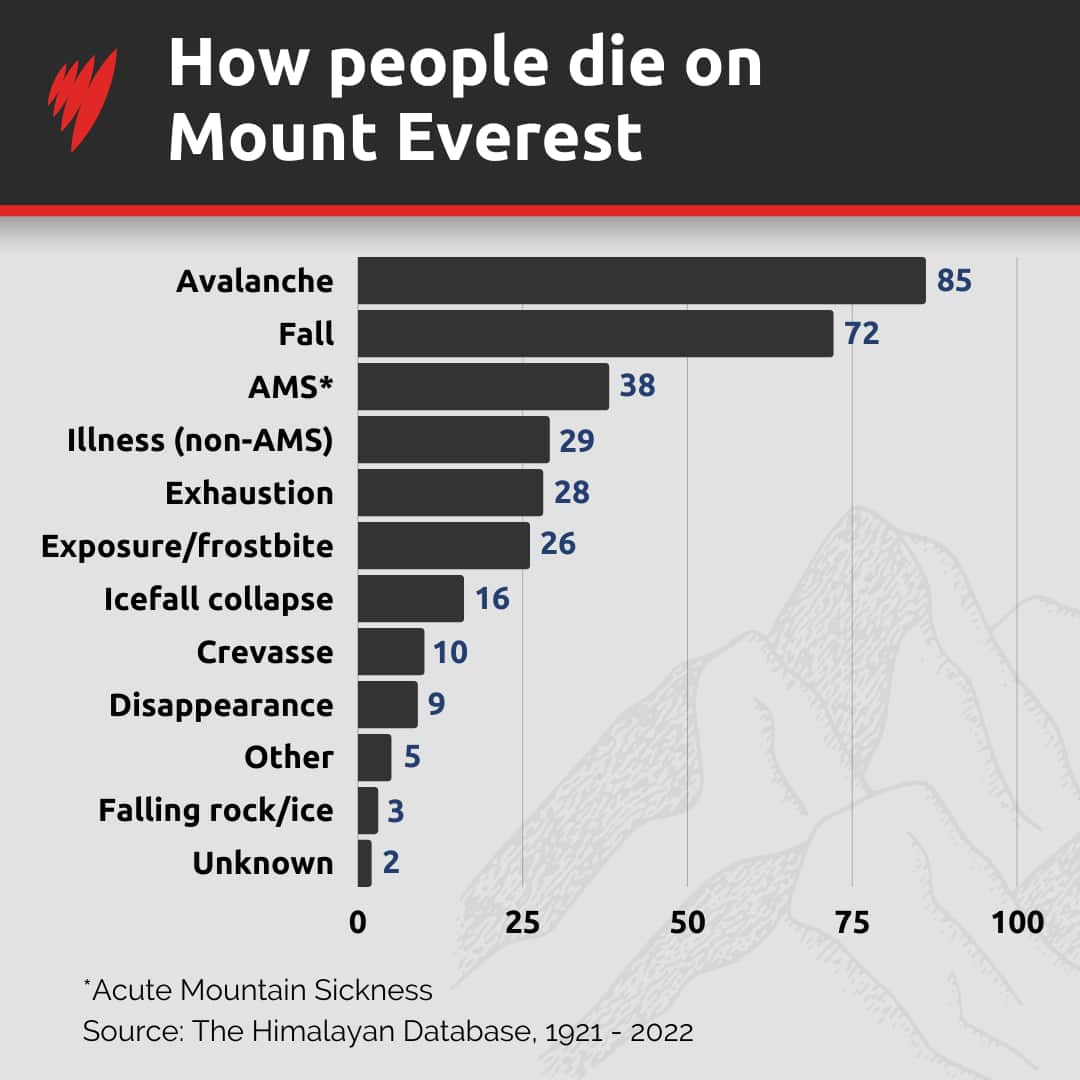

“Due to the worse weather, we lost more members this season [and] hundreds of members faced frostbite due to bad weather,” he said in a statement.

Temperatures at the summit are never above freezing and during the peak season for climbing the average is around -26C.

Khatiwada said if the number of climbers permitted was spread out evenly across the season, it would be safer: “On average, 16 members per day for summit is not so crowded”.

But the weather has meant fewer days for climbing, he said, resulting in overcrowding in what’s known as the ‘death-zone’, the area above 8,000 metres where there is a lack of oxygen.

“It seems quite [crowded] just due to unfavourable weather which creates [a] shorter window for climbing.”

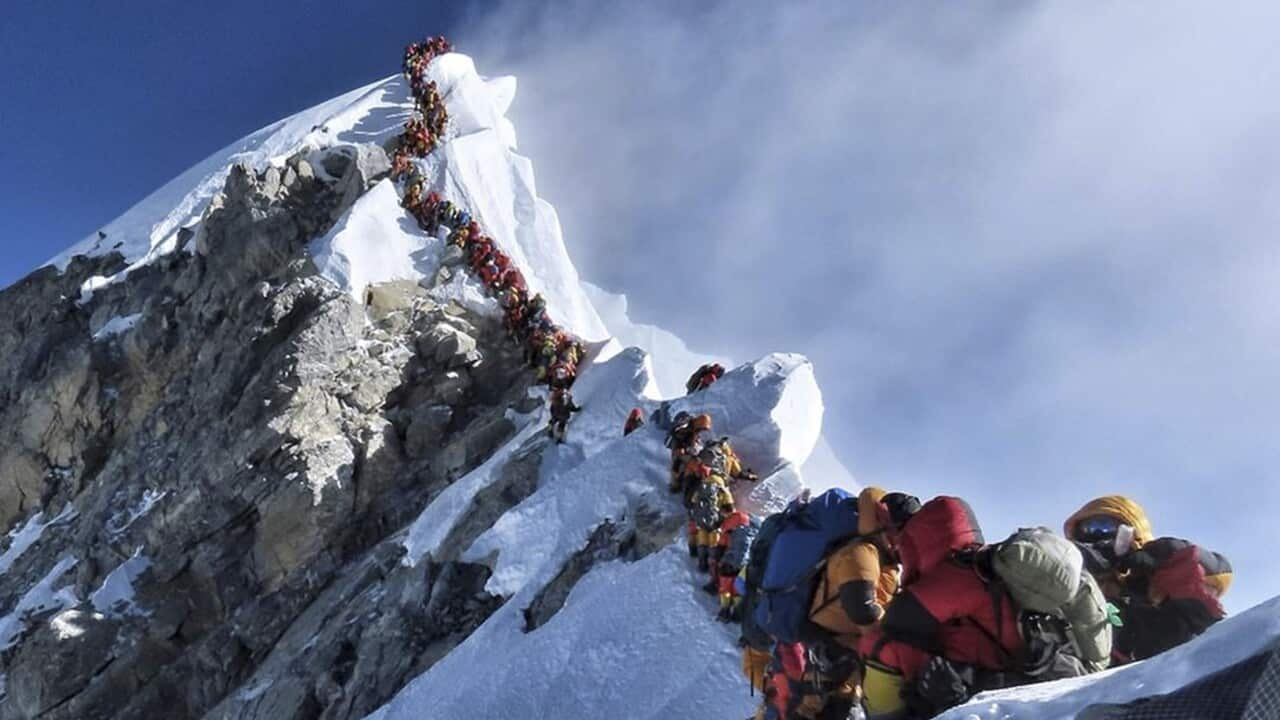

In 2019, there were reports of fatalities in a stand-still queue in the death zone and climbers stepping over others who were dead or unresponsive.

Alan Arnette, an American mountaineer who summited Mount Everest in 2011 and writes a blog about the climbing season, said overcrowding is an increasingly frequent and dangerous occurrence.

“If you’re up there and you’re in a line of 40 or 50 or 100 people, it’s like being on a single lane highway … you can’t pass them because everyone is clipped into the same safety rope,” he said.

“If the person in front refuses to move over because they’re moving too slow, or if their sherpa or guide can’t get them to move, then everybody queues and begins to run through their supplemental oxygen.

“There's a phenomenon called 'summit fever', where you get so obsessed with getting to the top that you suspend reality, you suspend good judgement, and you make bad decisions.

“You run out of oxygen at 8,000 metres, you will die.”

In 1984, Tim Macartney-Snape and Greg Mortimer became the first Australians to reach the summit of Mount Everest. The pair climbed without using supplementary oxygen via a new route on the North Face.

“It was incredible being able to go to the world’s best-known mountain ... and have it all to ourselves,” Macartney-Snape said.

“Getting to the summit was only fully realised at the last minute … [we saw] the most fantastic sunset you could ever believe … there was every colour of the rainbow in the sky, it was the most wonderful feeling looking out on the world, being totally alone and being overpowered by the wonder of it all.

“But you can’t really let yourself get too carried away because it was getting dark, and we were up there without oxygen, so the main thought was 'we’ve got to get down alive.'”

Macartney-Snape calls the overcrowding and bottlenecks on the mountain in recent times, “a nightmare scenario”.

“One of the things that allows you to combat cold is that you’re moving … there’s no win at staying put above 8,000 metres,” he said.

“You’re not so aware of what’s going on in your body at altitude because of the lack of oxygen and your brain is a little bit flaky.

“If the queue’s stopped because someone is having a problem on a difficult part, you’re watching your life tick away.”

Tourism is one of Nepal's largest industries and this season officials issued a record 479 summit permits for Mount Everest. Permits cost about $16,500 and require some mountaineering experience, but the government insists it is not commercialising the mountain.

Nepal’s Ambassador to Australia, H.E. Kailash Raj Pokharel, said: “The demand is very high due to various reasons and many people would like to climb, but certainly our intention is not to overcrowd Mount Everest, it should be manageable and safe.”

On safety, he said: “It’s a question sometimes if the inclement weather happens, and if the preparation is not well, in particular, the oxygen cylinders required should be adequate.

“If for one or two days the weather is clear, everyone wants to rush.”

Many of those who have died are locally employed guides.

There are calls for the government checks needed to issue a summit permit to be more rigorous to ensure inexperienced climbers are not left vulnerable.

Tshiring Jangbu Sherpa has been a guide on Everest since 2003 and has summited Everest three times. He is also the secretary of the Nepal National Mountain Guide Association. He says one of the hardest parts of his job is telling a climber they cannot continue to the summit.

“It’s quite challenging because they’ve paid for the summit and people are only thinking about getting to the top … their goal,” he said.

“In my experience when guiding, I need to check the condition of the clients to see if they are strong.

“It depends on the weather conditions too – and the wind conditions, if there are strong winds there is no option, I have to tell them we need to turn back. It’s not only dangerous but also the possibility to get frostbite.

“Sometimes we need to decide, it’s a strong decision.”

He worries the permit system is putting climbers at risk.

“There are thousands of people who want to summit, I think that's not a good idea,” he said.

“We should check their skill, check their experience, if they are technical enough, if they have climbed before to some 8,000 metres.

“If they had a good experience, then we should give them permission.”

That suggestion is supported by Macartney-Snape.

“It’s an unfair system; if you have a lot of resources, i.e. if you have a lot of money, you can virtually pay your way up to the top,” he said.

“Most of Nepal, no tourists go to and they have fantastic mountains, wonderful peaks, so the government could say, 'if you want to go to Everest you’ve got to qualify.'”

He suggests prospective summiteers climb a number of peaks, beginning at a 6,000 to 7,000-metre peak in a designated remote region where there is limited tourism, followed by a 7,000-plus metre peak elsewhere in the country before qualifying to climb Mount Everest.

“What that will do is take the pressure off the Everest region and deliver the benefits of tourism to the poorer parts of the country,” he said.

Pokharel said the government is considering creating a more distinct set of criteria for climbers to acquire the summit permit.

Griefline supports anyone experiencing grief on 1300 845 745.

Would you like to share your story with SBS News? Email yourstory@sbs.com.au