In January this year, an unprecedented wave of 'TikTok refugees' migrated to the Chinese social media platform RedNote (Xiaohongshu in Mandarin), ahead of a potential United States ban on TikTok.

Less than a year later, a similar label has emerged: 'under-16 refugees'.

The term surfaced after Australia's social media ban officially took effect on 10 December, making Australia the first country to prohibit children under the age of 16 from using certain social media platforms.

The ban applies to 10 platforms: Facebook, Instagram, Kick, Reddit, Snapchat, Threads, TikTok, Twitch, X and YouTube.

Platforms like RedNote and Douyin — the Chinese version of TikTok — are not included on the list.

Other predominantly non-English platforms are not yet included in the ban, such as KakaoTalk, widely used among Korean communities, and Line, a popular messaging app in Japan and Taiwan.

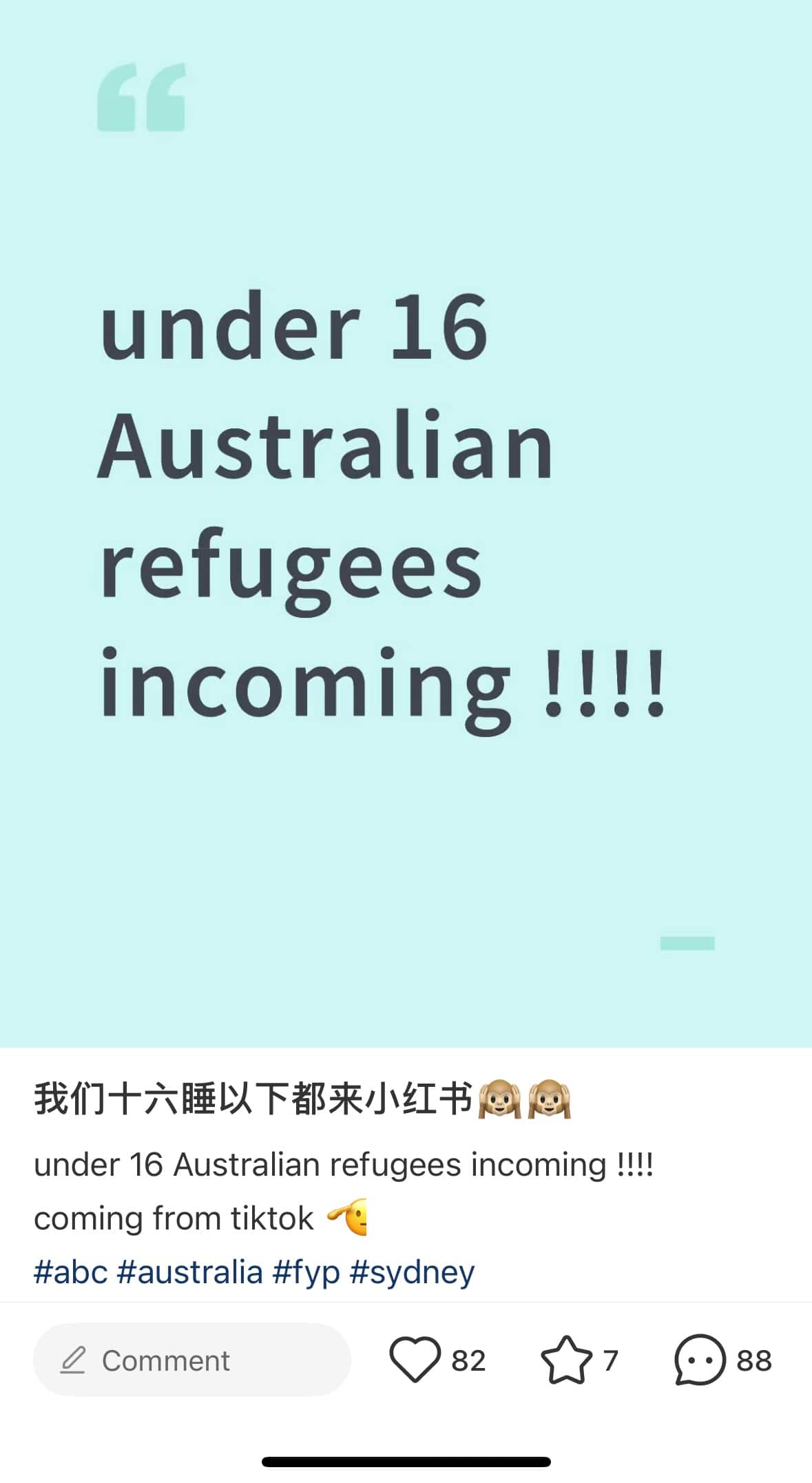

On RedNote, a user identifying themselves as an 'ABC' (Australian-born Chinese) posted a message reading "under 16 Australian refugees incoming", attracting hundreds of interactions within hours.

"Please don't post your photos. I don't want this app banned in Australia," one commenter wrote.

"They wouldn't have any reason to ban it," the original poster replied.

'The government hasn't really stepped in'

Fifteen-year-old Sophie Shan studies at Mercedes College in Adelaide. Since Australia's social media ban came into effect, she has been unable to access Snapchat, Facebook or Instagram — but her RedNote account remains unaffected.

Shan was born in China and migrated to Australia with her parents at the age of eight.

"I use RedNote a lot to look things up. I also have the Chinese version of TikTok, Douyin, and I use that as well," she said.

"I think because it's mainly used by Chinese people, the government hasn't really stepped in to regulate it yet."

Wenjia Tang, a postdoctoral researcher in digital culture at the University of Sydney, said the government's social media ban places bilingual teens and monolingual English-speaking users into different digital realms.

"The aim is not to understand how all cultural groups use social media. Instead, the focus [of the ban] is largely on the dominant group — English-speaking users — and how they are affected by social media," she said.

"That doesn't mean Chinese-language platforms are unimportant, nor does it mean the regulatory framework is inherently unequal. But for now, platforms used by minority communities or in other languages have not been included in the regulatory framework."

Compared to TikTok's 10 million Australian users and Instagram's 19 million, as reported in government eSafety data, RedNote's market share remains relatively small.

In late 2024, The Conversation reported the platform had 218 million monthly active users globally, including around 700,000 in Australia.

However, RedNote's profile in Australia is undeniably growing.

In the lead-up to this year's federal election, SBS Chinese reported on the growing number of political candidates turning to platforms like WeChat and RedNote to reach out to voters.

Tang said RedNote could become an alternative option for under-16s who are unable to access the social media platforms they are familiar with.

"The 'TikTok refugee' phenomenon already demonstrated that users are willing to migrate," she said.

"While that migration was short-lived, it doesn't mean RedNote couldn't once again become the next destination — or a substitute — if other platforms are shut down."

She said RedNote's design is similar to Instagram and TikTok, with a strong focus on images and short-form video, so new users don't need to learn the platform from scratch.

"I think its youthful appeal, localisation and real-time content updates align well with the profiles and usage habits of teenage users," Tang said.

Bilingual teens more likely to migrate

Tang acknowledged that turning to RedNote would not be the first choice for most Australian teenagers, and even if some did make the switch, a large-scale migration was unlikely.

"Based on what we are currently observing, if young people still want to use social media, their first instinct is not to look for a new platform, but to find ways to circumvent the legal restrictions," she said.

However, those who already have an interest in the platform or come from Chinese-language backgrounds are more likely to turn to RedNote or spend more time using it when previously available options are unavailable, Tang said.

Fourteen-year-old Ethan Guo, who lives in Brisbane, said Instagram and Discord were the social media platforms he used the most before the ban came into effect. Discord was not included in the ban.

When asked whether he would consider switching to RedNote or other Chinese-language platforms that remain accessible, Guo answered without hesitation: "No."

"I can't read Chinese and my Chinese is pretty bad. And I don't really use any of the Chinese social media," he said.

"I think the other large reason is the fact that almost none of my friends are on it. And trying to get them on it with me would be a pain. So I really just cannot be bothered."

Tang said the "social" aspect of social media is crucial — platforms feel safer and more welcoming when users are surrounded by familiar people.

"Young users don't see RedNote as their new TikTok or their new Instagram," she said. "Because that would require a large-scale community migration, not just moving platforms, but also moving their social connections. Only then would it feel like the same kind of platform."

She said the absence of regulation does not guarantee long-term safety or stability.

"It shouldn't be assumed that just because RedNote is not currently regulated, it will always be a safe or transferable space. If a large-scale migration were to occur, it could become the next target of policy intervention," she said.

Platforms adapt to shifting user demographics

In response to language barriers faced by non-Chinese speakers like Guo, RedNote has also started adapting.

Following the 'TikTok refugee' influx earlier this year, the platform rolled out significant system upgrades to attract overseas users.

It now offers real-time translation and allows users to set the interface language to English, Japanese, Korean, French and other languages.

The changes appear to have had some early impact, helping retain overseas users who initially downloaded the app out of curiosity.

Under a RedNote post reading "Miss the time when TikTok refugees were here", numerous US users replied: "I'm still here."

"I'm just not a refugee anymore. I'm a permanent resident," one comment read.

This story was produced in collaboration with SBS Mandarin.

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.