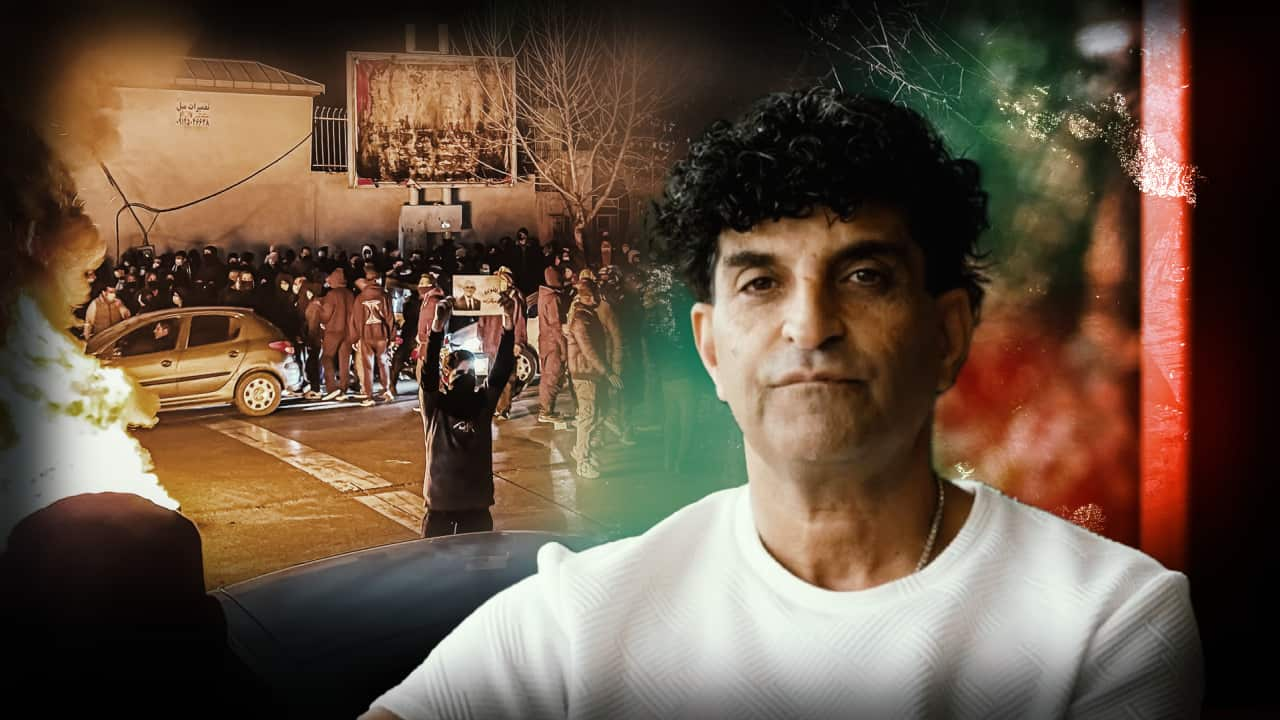

For Mohsen Haghshenas, watching Iran's mass protests from Australia triggers a mix of emotions.

"On the one hand, [there is] a feeling of fear, worry, anxiety, and nightmares," he told SBS News.

"I see nightmares. I'm very worried about my family. I'm very worried about my friends.

"On the other hand, a sense of freedom and pride in my compatriots, in my country, that we are a people who love freedom and that we have been fighting for freedom in the country for almost half a century," he said.

Protesters in several cities across Iran have been demonstrating for the past sixteen days.

Many have been killed.

The protests initially stemmed from economic grievances, but have evolved into an anti-regime movement.

The regime has reacted by cracking down on the protesters and imposing an internet blackout since Friday morning, according to Netblocks, a global internet monitoring organisation.

"They say Iran is the graveyard of the living. What's happening now is that it's as if they're in another world where it's impossible to contact them. It's as if they're dead, or it's as if I'm dead," Haghshenas said.

Amid the internet blackout, there has been difficulty verifying the death toll, and human rights organisations fear it could be much higher than what's been reported.

According to the United States-based Human Rights Activist News Agency (HRANA), 646 people have been killed in the demonstrations, including 505 protesters, nine children, 133 military and law enforcement personnel, one prosecutor, and seven non-protesting civilian citizens.

Like many other Iranians abroad, Haghshenas has been left in the dark about what is going on in his country for more than 100 hours.

He worries for his two daughters, aged 17 and 28, whom he had to leave behind less than three years ago. One of them expressed anxiety during their last phone call.

"The last time I had contact with her was in the early days of the protests, during the demonstrations," Hahghshenas said.

"She was very scared. She was very worried and told me she wished she were here with me."

A limited number of people in Iran have been able to connect to the internet via Elon Musk's Starlink satellite, however, reports indicate its networks have also been disrupted in Iran.

US President Donald Trump said on Monday that he plans to speak with Musk about restoring connection in Iran amid pressure to support internet freedom in the country after US funding cuts last year.

Dara Conduit, a lecturer in political science at Melbourne University, said the regime uses internet blackouts so that both the international community, and the rest of Iran, can't see what's happening on the streets and "can't see the violence that's taking place".

"Internet blackouts are extremely effective in this way because it basically stops people [from gathering]. The only thing that works after that is word of mouth," she told SBS News.

"The regime has started to respond in the only way it knows how to respond. That is with blood."

'We are not terrorists'

Getting information from Iran, let alone verifying facts, has become almost impossible.

Iranian state media has said dozens of members of the security forces have been killed, and the government has declared three days of national mourning for those security forces killed.

HRANA reports an additional 579 deaths remain under review, while Norway-based NGO Iran Human Rights warns that some estimates place the death toll at closer to 6,000, but with the caveat that it's "extremely difficult to independently verify these reports".

SBS News approached the Iranian Embassy for comment, but hasn't received a response at the time of publication.

Daniela Gavshon, the Australian director of Human Rights Watch, said the organisation is "receiving harrowing reports of escalating numbers of people being killed, beaten and arrested".

"In the earlier parts of the protest, we were able to verify that information. With the internet shutdown taking place, it's become a lot harder, and we're working to investigate some of those killings.

"We are really concerned that they're consistent with what we have seen in the past with these brutal crackdowns."

Multiple Iranian officials have called those in the streets "terrorists" and "rioters", with Iran's Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, saying "rioters should be put in their place" in the first days of the protests.

Haghshenas is no stranger to Iran's protests, having sought refuge in Australia after being jailed for his protest activities in 2023, during the 'Woman, Life, Freedom' movement.

Those protests were triggered by the death in custody of Mahsa Jina Amini, who was arrested for allegedly violating the country's mandatory hijab rule.

"We came to the street, we just wanted freedom. We had no right to be tortured … because we are not terrorists, we were not, and we do not want to be," he said.

"We didn't have any weapons. There was no violence. But they quickly took out their weapons and shot us."

'We're not just stories'

Iran has a long history of protest movements, with the 1979 revolution contributing to bringing the current Islamic Republic to power.

Since then, demonstrations have been triggered by a wide range of issues, including the crackdown on women's rights, political freedoms, censorship, corruption, environmental issues and economic hardship.

"After more than 40 years, the Iranian regime has [courted] an incredibly broad-based protest movement," Conduit said.

The economy is probably the one that is felt most broadly, and formed the narrative that kicked off the latest wave of protests, she said.

"But there's no doubt that all of the themes that played into the previous protest movement, including the Women Life Freedom Movement of 2022, are feeding into this."

"This has not come out of nowhere. This is not a protest that began a couple of weeks ago."

These grievances are also expressed by some members of the Iranian diaspora in Australia.

Iranian Australian artist Nazanin has painted a mural in Melbourne's famous Hosier Lane depicting Khamenei with crosses on his eyes.

SBS News has not used her full name.

"For me personally, it was a way to cross over the barrier of opposing the dictatorship … [to] actually looking them in the eye in the artwork," she told SBS News.

"I had to keep looking at his face for a pretty long time."

While painting the mural and being filmed by SBS News, she chose to wear a mask to cover her face, fearing retribution.

"I am really begging anyone who's seeing this to think about the humanity of people in Iran. We're not our government. We're not just numbers."

"We're not just stories on social media. We are real human beings with hopes and dreams," she said.

Thousands of kilometres away, the Australian government has urged the Iranian regime to stop the bloodshed, with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese saying the government stands "with the people of Iran in fighting against what is an oppressive regime, one that has oppressed its people".

"One that is, I hope ... removed by the people."

Iranian Australians such as Nazanin and Haghshenas remain hopeful for change. Many are waiting for a call from home, while some are dreaming of being on the streets in Iran alongside their "friends".

"What I really wish now is that I were in Iran, next to the fighters and next to my family, and at least whatever happened, we would have been together," Haghshenas said.

"You know, if there had been a massacre, we would have died together for freedom. If there had been a celebration after freedom, we would have celebrated together."

This story was produced in collaboration with SBS Persian.

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.