For South Vietnamese veterans of the Vietnam War, April 30, 1975 was the day they lost their country.

On that day, the North Vietnam communist army finally won the drawn out battle that had seen a million Vietnamese people lose their lives.

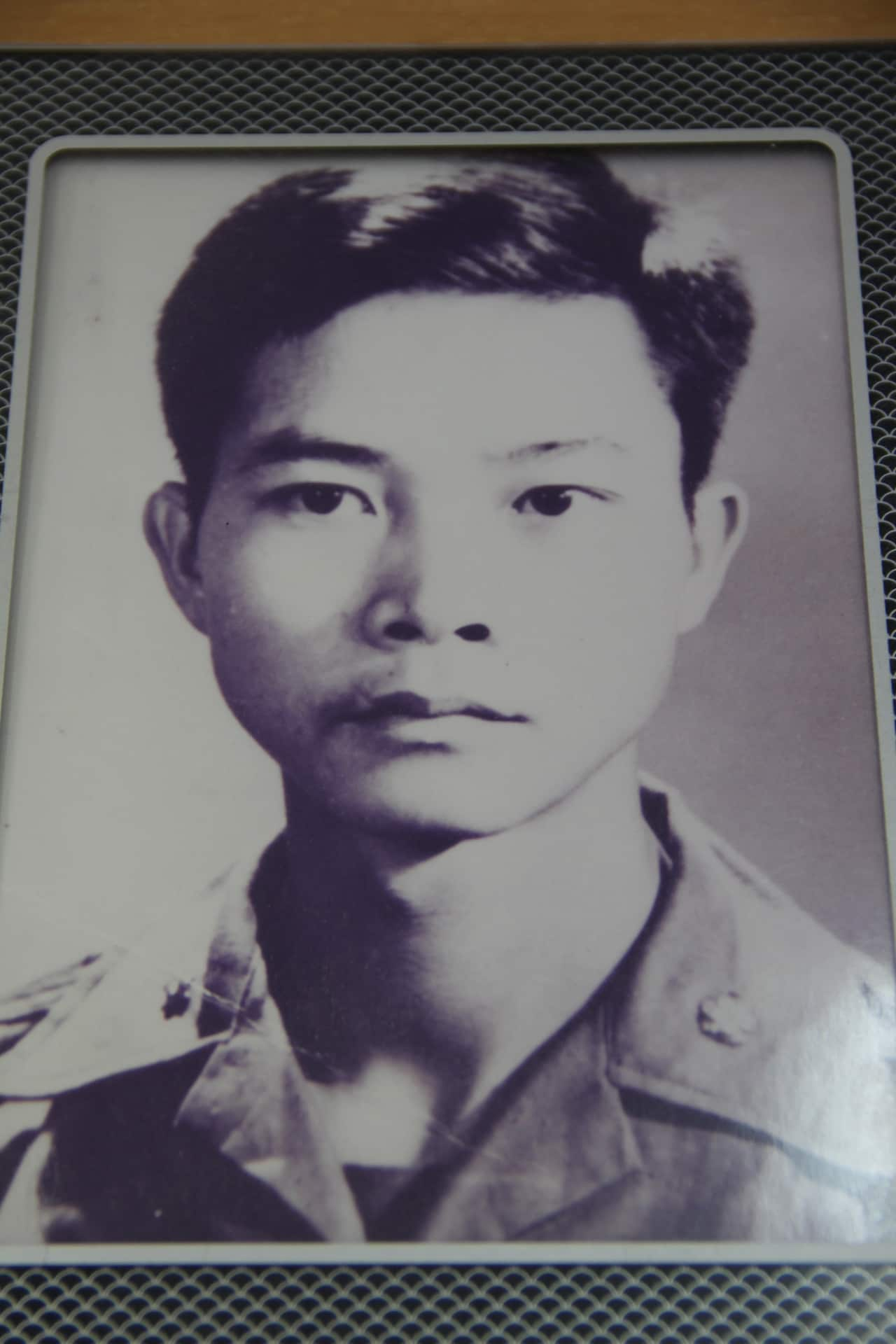

But for South Vietnamese soldiers like Al Chi Hoang, the fight was far from over.

In 1954 he and his family and left their home in North Vietnam on foot to escape the communist regime and had settled in the country's south.

Then in 1971, Mr Hoang, a 19-year-old law student, was conscripted into the South Vietnamese army and began about 10 months of basic military training.

"The war was terrible then, in the early 70s," he told SBS News.

"As a soldier I was sent to the 18th division infantry and that was in direct fighting. In 1972 it was the final step of the Vietnam War and it came to a very, very high intensity.

"I was maybe 20 years old and I was put on a chopper and went directly into the battle.

"The first battle I was in was An Loc, which was a very big battle. It was one of the biggest battles in Vietnam."

Monash University Associate Professor Nathalie Nguyen told SBS News the Vietnam War was a war between two Vietnams - communist North Vietnam and non-communist South Vietnam - as well as a proxy war between the communist bloc and the democratic west.

She has written a book, to be released on May 9, called South Vietnamese Soldiers: Memories of the Vietnam War and After.

"More than 250,000 South Vietnamese soldiers died during the war,” she told SBS News.

"I felt the South Vietnamese soldiers were very much forgotten."

She said there were no exact figures of the numbers of South Vietnamese veterans who came to Australia, but the figure was possibly about 15,000.

“The oldest veteran I spoke to was born in 1917 and he had fought in WWII in North Africa for the French,” Dr Nguyen said.

"The youngest veteran was born in 1955. There were a lot of kids in the war – a lot of veterans were only 17 when they joined the army.

"Quite a few veterans not only volunteered to serve but volunteered to serve in the elite units like the rangers and the airborne divisions, which had the highest death rate."

Mr Hoang said the South Vietnamese soldiers were essentially fighting a well-equipped North Vietnamese army "with one hand tied behind the back" once the Americans and Australians pulled out in 1972, leaving the South Vietnamese to their fate.

America also failed to follow up on promises made to the South Vietnamese to provide military aid and support.

"During the 70s there was a lot of opposition from the anti-war movement in Australia and in the US but at South Vietnamese we follow out elders," he said.

"They sacrificed for their country so we did the same."

Dr Nguyen said many South Vietnamese veterans still believed very strongly in the cause they were fighting for more than 40 years ago.

"They were proud to serve their country," she said.

She said at the end of the war, South Vietnamese soldiers not only lost their country, but their freedom, imprisoned in "bamboo gulags" or re-education camps for years.

Mr Hoang would remain in one of these camps for the next seven years, which included one year in solitary confinement.

"In the last days of the war I was in the headquarters of a division which meant I had the facility to go, but I decided not to," he said.

He said he was the last person to leave the headquarters.

"I was not a good prisoner because quite a few times I challenged them because I knew the law and I knew it wasn't right."

When he left the concentration camp, after years of horrific treatment and starvation, he weighed just 45 kilograms.

"We survived by the solace of other prison mates: we believed they were wrong and sooner or later they would fall because they were not supported by the people's hearts."

A few months after he was released his family helped him to bribe some fishermen who brought him to Australia by boat.

Mr Hoang now works in the south west Sydney suburb of Cabramatta as a solicitor and proudly marches in Sydney every Anzac Day, remembering his country, the friends he lost and hoping still for a completely free Vietnam.

"Even now we still believe the war shouldn’t have ended that way because we had the cause," he said.

"I do believe South Vietnamese veterans are quite happy because they do believe the Australian opinion is now more understanding about the Vietnam War."

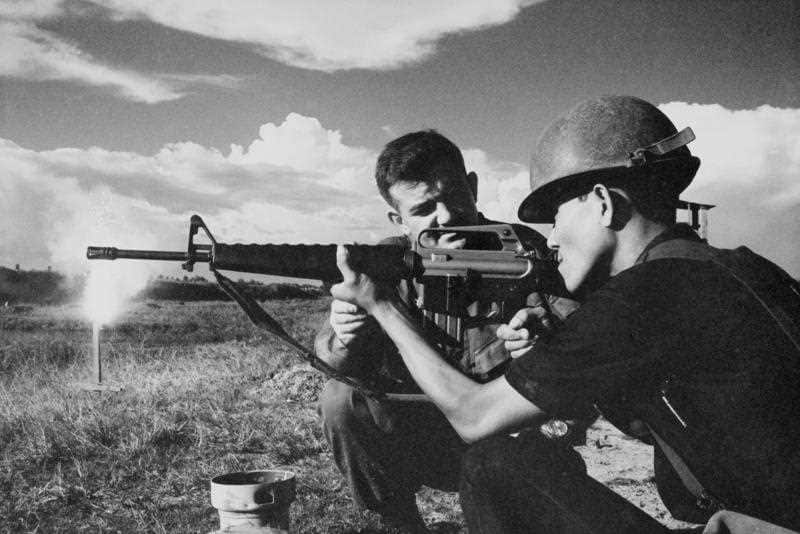

Head of military history at the Australia War Memorial, Ashley Ekins, told SBS News most Australian Vietnam War veterans, particularly those who served in the Australia Army Training Team, had a high opinion of South Vietnamese soldiers.

He said when Australian troops were hastily withdrawn in 1972 there was a strong feeling among them that the job wasn't finished.

"They came home feeling they had let the South Vietnamese down," Mr Ekins said.

"It's one of the big grievances Vietnam veterans had – it wasn't just that they were involved in an unpopular war and they came home to people who denied their service or ignored it altogether.

"They viewed it as dishonourable and they felt so bad about leaving the soldiers.

"They felt the job wasn't done."

Mr Ekins said there have been many Australian veterans who have worked hard to reconnect with South Vietnamese soldiers they knew during the war and have been able to meet them once more.

Dr Nguyen said Australian veterans and the Returned Services League had welcomed South Vietnamese veterans, who had been marching on Anzac Day since the 1980s.

"In the 1980s it was still a pretty small Vietnamese community.

"People who … witnessed the marches said the numbers of veterans marching compared to the size of the community was incredible."