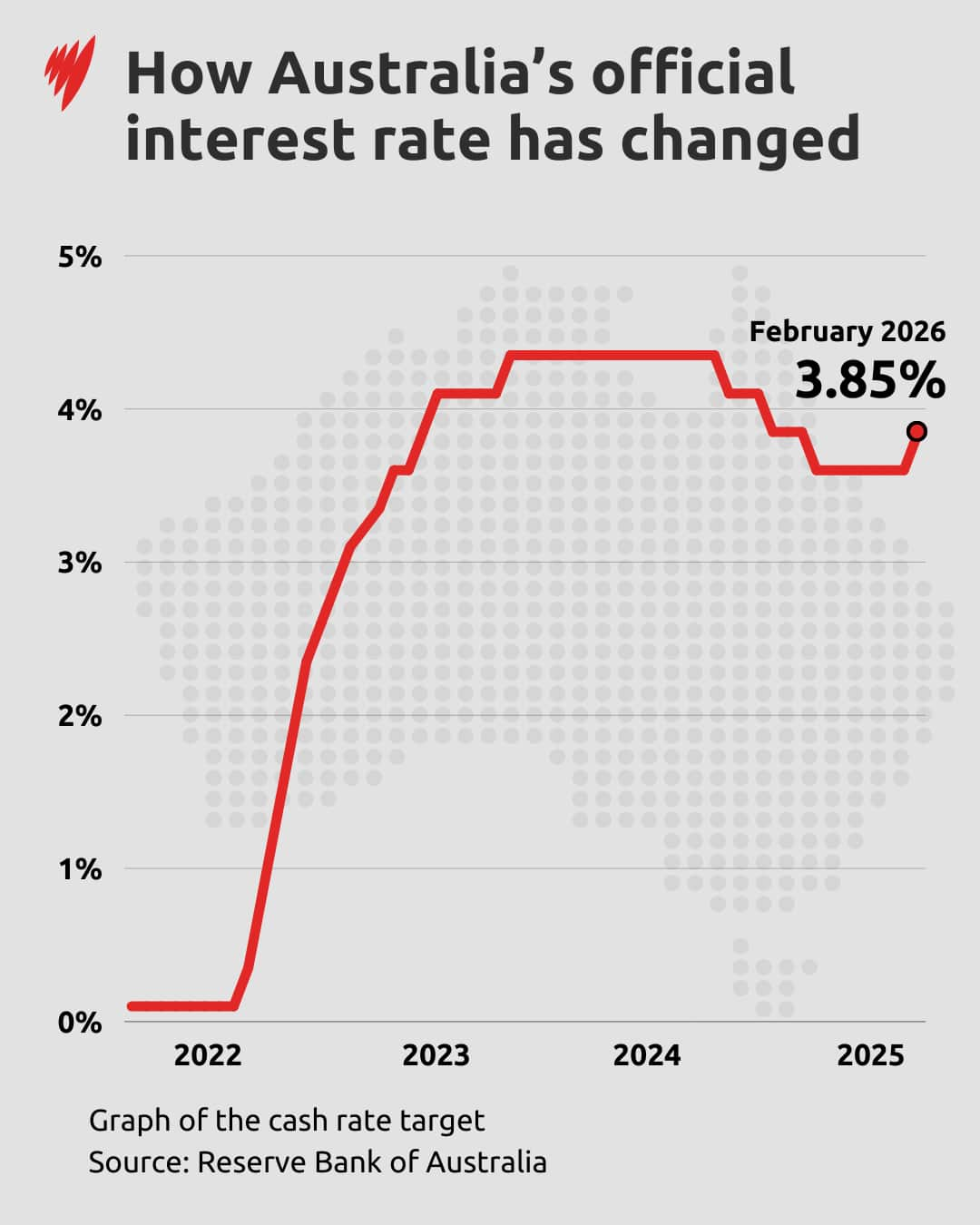

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) this week lifted interest rates for the first time in two years, and one key factor was behind the decision: inflation.

In an attempt to slow spending and curb inflation, the central bank's monetary policy board voted unanimously voted to lift the cash rate by 0.25 percentage points, to 3.85 per cent.

For borrowers, the news is an unfortunate sign that some belt-tightening time may be on the horizon.

Acknowledging this, RBA governor Michelle Bullock said: "I know this is not the news that Australians with mortgages want to hear, but it is the right thing for the economy."

So — what's the cash rate, what's inflation, what drives an increase, and what can be done about it?

What is inflation?

The inflation rate is the rate at which the price of consumer goods is increasing.

It's tracked using the Consumer Price Index (CPI), published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The CPI is reported monthly, with an additional quarterly release.

The RBA aims to keep inflation within its target band of 2-3 per cent. Over recent months it has been creeping higher, with headline CPI inflation rising to 3.8 per cent in the year to December 2025, up from 3.4 per cent in the year to November. Measures of underlying inflation — which strip out volatile price swings like petrol — have also lifted, with trimmed mean inflation at 3.3 per cent, up from 3.2 per cent a month earlier.

The RBA's monetary policy board meets eight times a year to decide whether to raise, cut or hold the cash rate — using it to cool down spending when prices are rising too fast, or to support the economy when growth is weak.

With "underlying momentum of inflation ... too strong" as it convened for its first meeting of the year, the board voted unanimously to raise rates.

Jack Thrower, senior economist at progressive think tank the Australia Institute, said interest rate hikes worked by curbing the spending of those with large debts.

"If interest rates go up, then people with lots of debt, usually mortgage holders, will have to pay more in interest, which means they have less money to spend on other things," he told SBS News.

"If they start spending less money, then businesses will see demand for their goods and services go down, and they won't be able to put up their prices because fewer people want to buy their stuff."

He said this way, businesses could even be incentivised to lower prices to attract more customers.

What is the cash rate?

The cash rate is the key interest rate set by the RBA. It affects how much it costs banks to borrow money, and that flows through to the interest rates many of us pay — and earn — on things like home loans and savings accounts.

When the cash rate goes up, repayments on loans can rise, especially for people on variable-rate mortgages. People with savings may get higher interest on their bank accounts.

What's driving high inflation?

On Tuesday, the RBA gave several key reasons for higher inflation, including: growing private demand, capacity pressures greater than previously assessed, and a tight labour market.

AMP chief economist Shane Oliver said a rise in private demand referred to spending by Australian consumers on homes, construction, and investment.

"Capacity pressures" relate to the intersection of demand and supply in the economy. These can drive inflation when demand for resources is high, but output is constrained by fewer resources.

"If more demand appeared in the economy, then the economy doesn't have the capacity to expand production because it's running out of those resources, whether they're capital, like offices and machinery equipment, or whether they're people," Thrower said.

"If the business can't expand more, bring in more resources and increase its output when it sees more people wanting its goods, what it'll do instead is it'll put up its prices. And so when we reach these capacity constraints, we find that businesses start putting up their prices to earn bigger profits.

"That's what the RBA is worried businesses will start doing."

To counteract capacity constraints, Thrower and Oliver both stressed the importance of productivity.

"Productivity is basically the way we combine all those resources to make stuff. If we work more efficiently, then we can produce more with what we have," Thrower said.

"We could also increase it by building more factories and making more tools and equipment, or we could expand our workforce. We could bring in more migrants, for example. And if we did that, then we would have more workers and therefore we could produce more stuff."

Oliver warned that while a tight labour market was good news for workers, it could lead to upward pressure on inflation.

"Because workers, understandably, demand higher wages when there is greater demand for their services," he said.

Other 'one-off' pressures

Thrower said the RBA had acknowledged a handful of "one-off" and "unusual" events that weren't of serious concern, including expenditure on overseas holidays, and the withdrawal of federal and state electricity price subsidies across Australia.

Meg Elkins, associate professor of economics at RMIT University, said the December inflation rate was "unsurprising".

"Food and accommodation, you've got travel in there, you've got cultural activities. And if you think about the last couple of months, we've had lots of artists coming out, and we're paying more for our tickets than ever," Elkins told SBS News.

She pointed to "rational expectations" to explain consumer behaviours throughout 2025, amid three rate cuts.

"We base our behaviour on what we expect to happen next. Because there was an idea that rates would continue to come down, we factored that in, loosened the purse strings and spent a little bit more.

"And the reverse of that is now that we're being told to tighten our belts, I think people will also factor that in and spend less. So businesses that might expect demand to rise will increase their prices, and we don't want that spiral happening."

What can I do about it?

Not much, according to Thrower.

"It's a macroeconomic problem. It concerns the entire economy. And so it's difficult for individuals to do very much about it at all."

He said in the end, inflation was about whether businesses could increase their prices.

"We assume in a market economy like Australia's that firms are going to try and maximise their profits, and to do that, they'll often try and get as high a price as they can for their goods."

Thrower said a lot of the inflation we were facing could be driven by a lack of market competition across the biggest consumer goods firms, like groceries, insurance and airlines.

"In Australia, there's not a lot of competition and a lot of industries are dominated by a few large firms. Because there's only a few firms, they don't face a lot of stiff competition, and so consequently they have a lot of market power, and they're simply able to increase their prices easily.

"And every time there's this sort of increase in demand, that's what they choose to do."

Elkins says there are a few things Australians can do. Foremost was shopping around and exercising your right to purchase with the right companies.

"If you are a borrower, the onus is to put money aside and spend less and be strategic, shop around, don't pay the highest prices. And I think that sends a signal back to businesses," she said.

"And that's what we can do. The rest is now up to businesses and government to raise productivity."

But she warned the interest rate hike doesn't affect everyone equally, describing the gulf between self-funded retirees and those who rent or have a mortgage as "almost like a two-tier economy".

"If businesses sense that there's an excess demand out there, they will increase their prices," she said.

She added that this week's rate hike is signalling to the market that "consumers need to slow down".

It's why Michelle Bullock called the rate hike a "blunt instrument" to curb inflation.

Speaking to reporters on Tuesday, Bullock ackowledged the impact on households.

"For mortgage holders, this isn't a great outcome," she said. "But what's also not great for them, or for anyone else, is if inflation remains elevated.

"Ultimately, it is best if we get inflation under control, and our instrument is the interest rate."

Elkins says it's fairly obvious what the RBA expects average Australians to do: "Spend less, save more, and stop asking for big wage increases."

"But they'll never phrase that last one in that way."

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.