I was beginning a report on how tech companies are tackling ageing when a question emerged: How long do I want to live?

Any answer less than forever implies accepting death at some point. The idea of accepting death for myself may be one thing, but accepting it for my children is a completely different thing.

I would happily wish away death from their futures, but I wondered how they felt about death and longevity. I was unprepared for how emotional it would be to ask my kids for their thoughts on our mortality.

Their answers - as thoughtful and sweet, as macabre and dark - launched me into a query that would lead me halfway around the world for Dateline's The Death of Ageing story, in search of answers from some of the most prominent voices and brightest minds leading the charge on human longevity.

At the end of it all, no answers rang more true than those that set me on this journey in the first place, from the mouths of babes.

There are some who say that my kids may not have to face the ravages of getting old. Aubrey de Grey has gained quite a bit of notoriety from his TED talks about ageing.

He’s built an entire persona as death’s naysayer. He looks the part as well, wizard-like with a greying Merlin-esque beard.

“We have a completely, biologically invalid and incorrect idea that there is some kind of black and white wall between ageing itself - whatever we mean by that - and the diseases of old age, like Alzheimer’s, or cardiovascular disease or cancer.”

A simplified form of de Grey’s view is that ageing is a process in which our cells collect damage and, he believes it will soon be possible to not only slow that damage, but actually reverse it, leading to life eternal.

De Grey wraps his ideas in just enough science as to obfuscate them from a layman's inquiry.

When I expressed the conflict between my hope that his theories are correct and my journalistic scepticism, he replied, “Get a grip, grow up and stop thinking about whether you’re sceptical or you want hope. Just remember that you’re not a scientist yet and therefore, I know better than you.” It was less than confidence inspiring.

After meeting de Grey, it was easy to wonder if there’s much substance in the so-called longevity movement. But I found there are some very serious scientists, companies and investors who are working to extend our healthspan.

Google has started a company called Calico, which stands for the California Life Company. Its website sets out the mission, “Tackling ageing, one of life’s greatest mysteries.”

We’re not sure how they intend to go about it as we couldn’t get them to give us an interview, but just the mere fact that Google has made a target of ageing has shifted the conversation about human longevity from the fringe with de Grey to the realm of the possible.

But Google is a data company. What does data have to do with ageing?

“We’re heading towards a world that’s going to be massively data driven. The companies that are crushing it - Uber, Airbnb - are all data-driven companies. And companies that aren’t gathering data and using it to make decisions are going to be gone. They will be destroyed,” Dr Peter Diamandis told me. And he should know.

Diamandis is a venture capitalist from Silicon Valley who’s famous for founding Singularity University with Ray Kurzweil and for investing in such futuristic endeavours as space tourism and asteroid mining.

Peter sees longevity as the next chapter in the internet age and a huge business opportunity. I asked if genetics are going to be part of big data?

“The most valuable data. There’s 60-70 trillion dollars of wealth held in the hands of people over 60. And how much would they spend for an extra 10, 20, 30 extra years of healthy life? It’s a huge marketplace.”

Peter has put his money where his mouth is. He’s invested in Human Longevity Inc (HLI). A new company founded by Craig Venter. If there is a Darwin of the genetic age, it’s Venter.

His genome was the first to be fully sequenced at a price tag of around $100 million. Half joking I told Craig that being the first to sequence his genome was like landing on the moon, to which he quipped that it was, in fact, more rare. “We went back to the moon, didn’t we?”

He could be right, his genome is now the reference gene for all genetic study. Craig also drives an Aston Martin with 007 on its licence plates.

At HLI, Craig has built the world’s largest genetic sequencing centre. With it he has massive plans to change the medical industry by compiling one million fully sequenced genomes.

Each genome has a strand of nearly five billion proteins that determine everything from the colour of our eyes to how we metabolise caffeine, even whether your body odour is more on the offensive side or not.

But more importantly, your genes can determine how you will respond to a specific drug or medical treatment. Craig argues that by understanding our genetic maps, we can tailor medical treatment to the individual level.

And while longevity is in the name of his company, he is adamant that he’s not talking about living forever, but more about turning 95 into the new 75.

“You know the goal is not to get people to live to 120, it’s to get to whatever your normal lifespan is without a decade or two or more of debilitating disease.”

I’ve always been a fan of the poetry of Dylan Thomas and I couldn’t help but hear his poem, Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night, in the back of my head at each step of my journey:

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

But I was also reminded of something Franz Kafka famously wrote, ‘The meaning of life is that it ends.’ Aren’t death and life two sides of the same coin?

Then I met a jellyfish and karaoking scientist in a small seaside town in southern Japan, who challenged this very notion.

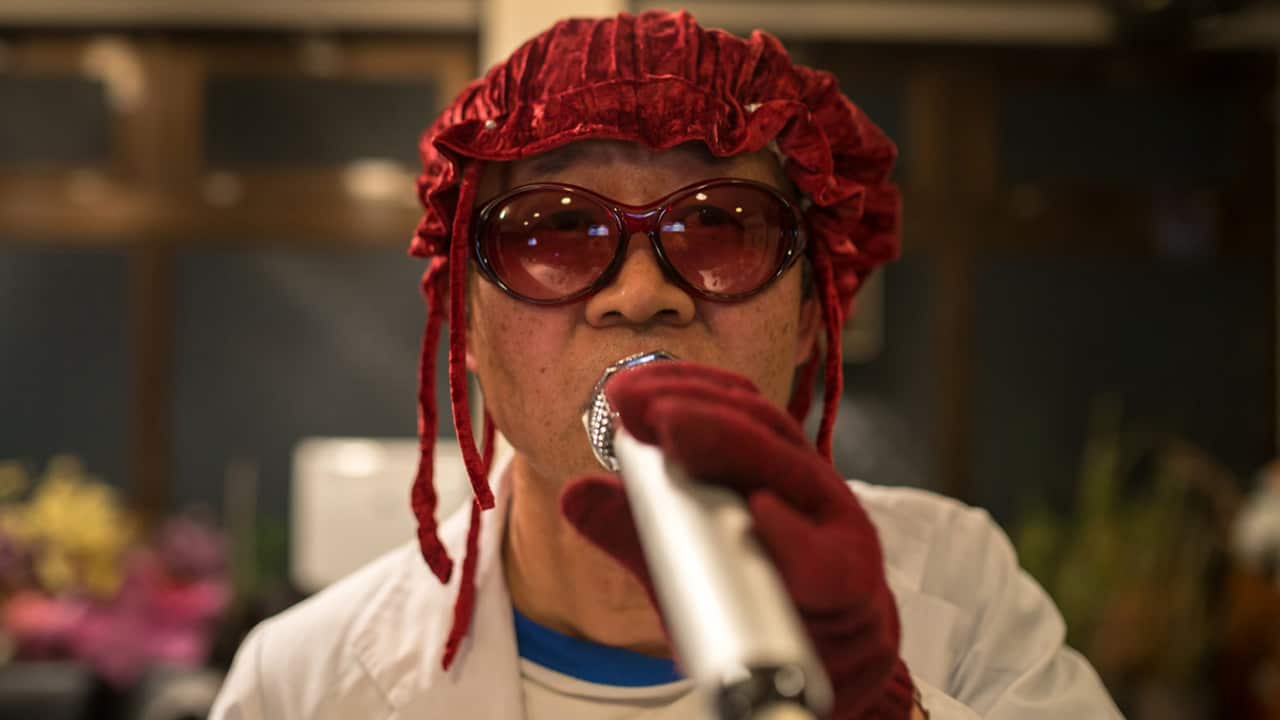

In a cosy karaoke bar, watching a scientist in a jellyfish costume perform original songs about his beloved jellyfish, I remember thinking that Professor Shin Kubota was an odd fellow and worrying that I had come halfway around the world to Shirahama, Japan, for someone who might be more character than substance.

But in fact, Shin is the world’s leading expert on the Turritopsis Dornii jellyfish, more commonly known as the immortal jellyfish.

These microscopic creatures have the unique ability to age as we do and then as their body starts to take on damage or trauma, they can reverse ageing and return to their polyp form before growing again.

Shin’s current crop of immortal jellyfish are on their 13th life. While Shin is fascinated with the biological possibility of immortality, he’s not so seduced by it as to wish for it for humanity.

“Humans are not really thinking about nature or the environment at all and we are changing the earth in a way that suits our needs only. This isn’t really good, actually it’s really bad for the rest of the 1.4 million species that live on earth. We are really making this a human-centric world.”

My interview with Shin, a biologist, turned surprisingly philosophical. But he was right, the idea of extending our lives may begin with science, but it leads to questions about the meaning of life and our place in this world.

For answers, I travelled to New Haven, Connecticut, and sat down with Shelly Kagan, who is the head of philosophy at Yale University.

He teaches one of the most popular courses on campus. It’s called Death. A marketer, Shelly is not.

Over the course of a semester, Shelly tries to teach his Ivy League students that ‘death is really the end.’

“Most of us go through life, I think, discovering that we are making or have made choices but haven't really reflected hard on whether those were the right choices to make or what were our reasons, were those good reasons?”

“I think recognising that death is really the end implies the finitude of existence. And then that has the implication then that it really behoves you to think hard, long and hard, about what is worth doing with your life,” he said.

Kagan’s tough-medicine approach to facing death may be philosophically valid, but that didn’t matter as I faced one of the toughest interviews of my career.

When I first asked my seven-year-old son Spencer how long he wanted to live, he said forever, so he could play video games for his whole life.

Then, I walked him through the philosophical primrose path of what forever actually means. Won’t you tire of playing video games? Do you really want to do that for 10,000 years?

So he changed his mind and decided that he no longer wanted to live forever. I wish I hadn’t done that. I was happier with his idea of an eternal Spencer. But, he’s right, the idea of living forever isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

I think what I really want is for this moment in time with my five children at the ages they currently are - with my daughter who treats everyday like it’s a musical, and my two sons who would be happy as could be endlessly playing Minecraft together, and my oldest son trying to tackle the injustices in the world by going to law school and even my little baby who reaches with every part of his pudgy little body when he sees a small jar of mushed peas.

I want this moment with these extensions of my genome to last forever, and I’m afraid that’s something that no scientist or venture capitalist or even mighty Google can help me with.

Click to read more about Josh's story, and see what he had to say about it on Twitter Follow @joshrushing

Dateline is an award-winning Australian, international documentary series airing for over 40 years. Each week Dateline scours the globe to bring you a world of daring stories. Read more about Dateline

Have a story or comment? Contact Us