A key question facing us all after Australia’s unprecedented bushfires is how will we do reconstruction differently? We need to ensure our rebuilding and recovery efforts make us safer, protect our environment and improve our ability to cope with future disasters.

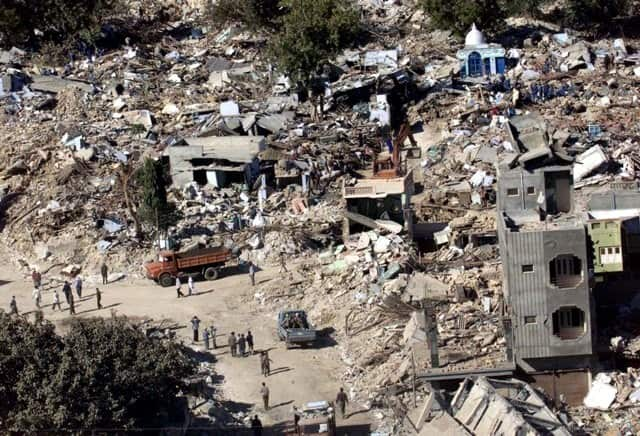

The quake in Gujarat state killed 20,000 people, injured 300,000 and destroyed or damaged a million homes. My research has identified two elements that were particularly important for the recovery of the devastated communities.

First, India set up a recovery taskforce operating not just at a national level but at state, local and community levels. Second, community-based recovery coordination hubs were an informal but highly effective innovation.

Rebuilding for resilience

Scholars and international agencies such as the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) have promoted post-disaster reconstruction as a window of opportunity to build resilience. By that, they mean we not only rebuild physical structures – homes, schools, roads – to be safer than before, but we also revive local businesses, heal communities and restore ecosystems to be better prepared for the next bushfires or other disasters.

This is easier said than done. Reconstruction is a highly complex and lengthy process. Two key challenges, among others, are a lack of long-term commitment past initial reconstruction and a failure to collaborate effectively between sectors.

Reconstruction programs require a balancing of competing demands. The desire for speedy rebuilding must be weighed against considerations of long-term challenges such as climate change adaptation and environmental sustainability.

There will always be diverse views on such issues. For example, planners may suggest people should not be allowed to rebuild in areas at high risk of bushfires. Residents may wish to rebuild due to their connection to the land or community.

Such differences in opinion are not necessarily a hindrance. As discussed below, managing such differences well can lead to innovative solutions.

What can we learn from India’s experience?

The 2001 Gujarat earthquake was declared a national calamity. My research examined post-disaster reconstruction processes that influenced community recovery – physical, social and economic. The findings from Gujarat 13 years after the quake were then compared with recovery processes seven years after the devastating 2008 Kosi River floods in the Indian state of Bihar.

Of my key findings, two are most relevant to Australia right now.

India’s government set up a special recovery taskforce within a week of the earthquake. The taskforce was established at federal, state, local and community level, either by nominating an existing institution (such as the magistrate’s court) or by establishing a new authority.

The Australian government has set up a National Bushfire Recovery Agency, committing A$2 billion to help people who lost their homes and businesses rebuild their communities. While Australia effectively has a special taskforce at federal and state level (such as the Bushfire Recovery Victoria agency), we need it at local and community levels too. Moreover, no such agency exists at state level in New South Wales.

Without such a decentralised setup, it will be hard to maintain focus and set the clear priorities that local communities need for seamless recovery.

Second, India’s recovery coordination hub at community level was an innovative solution to meet the need of listening to diverse views, channelling information and coordinating various agencies.

A district-wide consortium of civil society organisations in Gujarat established Setu Kendra – literally meaning bridging centres or hubs.

These hubs were set up informally in 2001. Each hub comprised a local community member, social worker, building professional, financial expert and lawyer. They met regularly after the earthquake to pass on information and discuss solution.

Bushfire Recovery Victoria has committed A$15 million for setting up community recovery hubs, but it remains to be seen how these are modelled and managed.

The community hubs in India have had many benefits. The main one was that the community trusted the information the people in the hub provided, which countered misinformation. A side effect of community engagement in this hub was their emotional recovery.

These hubs also managed to influence major changes in recovery policy. Reconstruction shifted from being government-driven to community-driven and owner-driven.

This was mainly possible due to the Setu Kendras acting as a two-way conduit for information and opinions. Community members were able to raise their concerns with government in a way that got heard, and visa versa.

Due to the success of coordination hubs in Gujarat after 2001, the state government of Bihar adopted the model in 2008. It set up one hub per 4,000 houses. In Gujarat, these hubs continued for more than 13 years.

The UN agency for human settlements, UN-Habitat, notes these community hubs as an innovation worth replicating.

We in Australia are at a point when we need to create such hubs to bring together researchers, scientists, practitioners, government and community members. They need to have an open conversation about their challenges, values and priorities, to be able to negotiate and plan our way forward.

Australia needs a marriage between government leadership and innovation by grassroots community organisations to produce a well-planned recovery program that helps us achieve a resilient future.

Mittul Vahanvati received funding from RMIT scholarship for PhD (2012-2018). She is affiliated with RMIT University's Climate Change Transformations Research Group; Bushfire Natural Hazards CRC and Urban Community of Practice (Red Cross and ACFID).

Dateline is an award-winning Australian, international documentary series airing for over 40 years. Each week Dateline scours the globe to bring you a world of daring stories. Read more about Dateline

Have a story or comment? Contact Us