Above: What’s it like arriving in Trump’s America after 4 years on Manus Island? Full story On Demand.

John Palmer, a former university professor, has always had a cause. For decades he urged Minnesota officials to face the dangers of drunken driving and embrace seat belts. Now he has a new goal: curbing the resettlement of Somali refugees in St. Cloud, after a few thousand moved into this small city where Palmer has lived for decades.

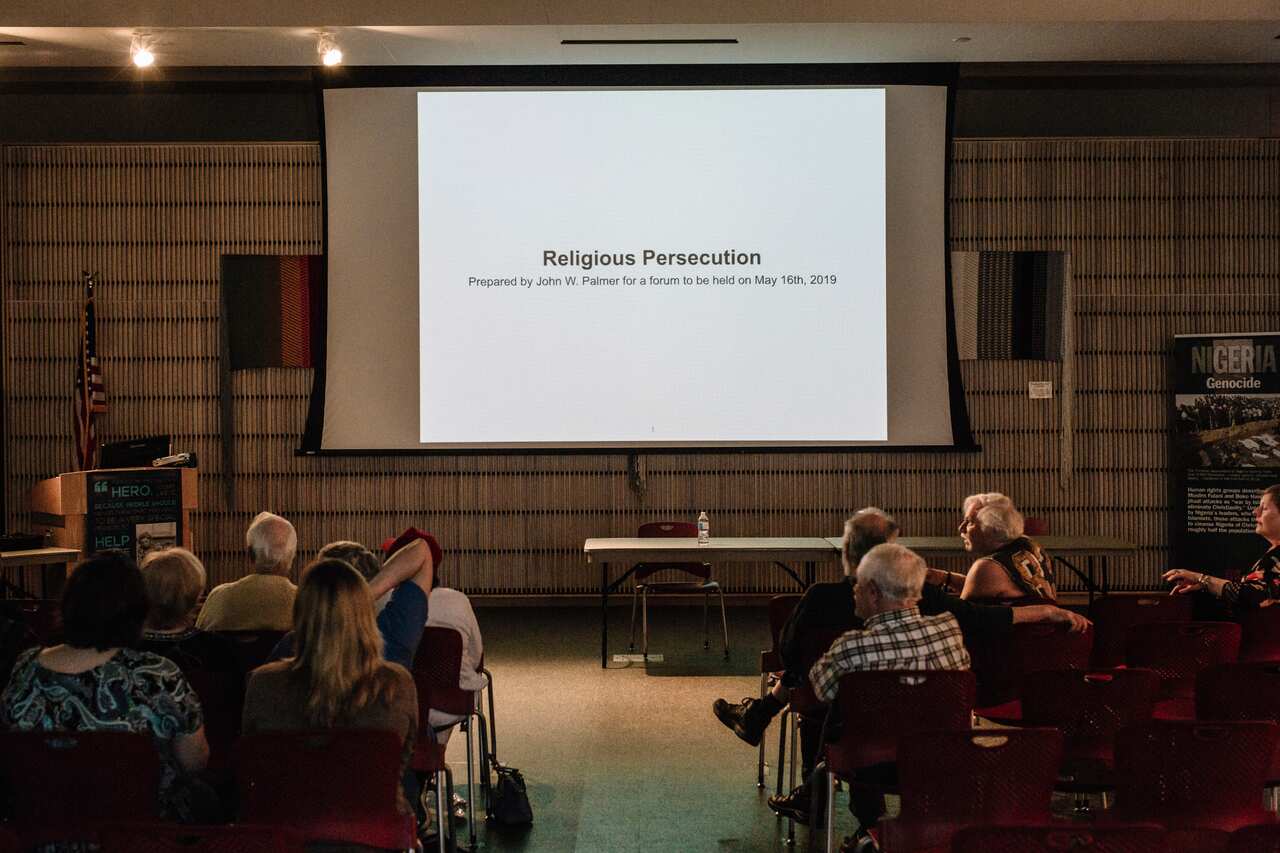

Every weekday, he sits in the same spot at Culver’s restaurant — the corner booth near the Kwik Trip — and begins his daily intake of news from xenophobic and conspiratorial sites, such as JihadWatch.org, and articles with titles like “Lifting the Veil on the ‘Islamophobia’ Hoax.” On Thursdays, Palmer hosts a group called Concerned Community Citizens, or C-Cubed, which he formed to pressure local officials over the Muslim refugees. Palmer said at a recent meeting he viewed them as innately less intelligent than the “typical” American citizen, as well as a threat.

“The very word ‘Islamophobia’ is a false narrative,” Palmer, 70, said. “A phobia is an irrational fear.” Raising his voice, he added, “An irrational fear! There are many reasons we are not being irrational.”

In this predominantly white region of central Minnesota, the influx of Somalis, most of whom are Muslim, has spurred the sort of demographic and cultural shifts that President Donald Trump and right-wing conservatives have stoked fears about for years. The resettlement has divided many politically active residents of St. Cloud, with some saying they welcome the migrants.

But for others, the changes have fuelled talk about “white replacement,” a racist conspiracy theory tied to the declining birthrates of white Americans that has spread in far-right circles and online chat rooms and is now surfacing in some communities.

“If we start changing our way of life to accommodate where they came from, guess what happens to our country?” said Liz Baklaich, a member of C-Cubed who unsuccessfully ran for St. Cloud City Council last year. She carries an annotated Quran in her purse. “If our country becomes like Somalia, there is nowhere for us to go.”

Minnesota’s biggest city, Minneapolis, has long struggled to incorporate a growing immigrant population into the city’s fabric, but the recent ascension of some former refugees into political power was taken as a sign of progress by many liberals. In central Minnesota, which is more conservative than the state’s urban centres, advocates for refugees fear that the resettlements could be met with more resistance.

Dave Kleis, the mayor of St. Cloud and a long-time Republican who now identifies as an independent, has voiced support for the resettlement program, but he has also drawn criticism for not forcefully denouncing groups like C-Cubed, which he refused to discuss in an interview. Kleis said the city was facing the same challenges as other parts of Minnesota and other changing communities around the country. St. Cloud, the state’s 10th-largest city, increased in population by 33 per cent over the last 30 years, to roughly 70,000 people. The share of non-white residents grew to 18 per cent from two per cent, mostly with East African immigrants from Somalia, Kenya and Ethiopia, and the numbers of Somalis are estimated to grow.

Their increased presence — and an attack at a mall in 2016, when Dahir Adan, a Somali-American refugee living in St. Cloud, stabbed 10 people — has emboldened a loosely connected network of white, anti-immigration activists who are trying to pressure local and state Republicans to embrace an increasingly explicit anti-Muslim agenda.

Kim Crockett, the vice president and general counsel of a conservative Minnesota think tank called the Center of the American Experiment, said she intended to eventually sue the state and challenge the resettlement program in court.

“I think of America, the great assimilator, as a rubber band, but with this — we’re at the breaking point,” Crockett said. “These aren’t people coming from Norway, let’s put it that way. These people are very visible.”

‘This is the Hatfields and McCoys’

Though it predates Trump, the opposition to migrant resettlement among some Minnesotans has been invigorated by the president, who has repeatedly demeaned refugees and Muslims, and who recently announced a restrictive immigration proposal that included cultural provisions such as preferential treatment for English speakers.

In St. Cloud, some opponents of the refugee program have taken the introduction of non-pork options in the local public schools as an attack on their way of life. The 2018 elections of Representative Ilhan Omar and Attorney General Keith Ellison, who are Muslim, fuelled xenophobic conspiracies that Muslim residents were planning a long-term coup to institute Sharia Law. They also point to individual instances of crime by Somali-Americans as proof of an innate predisposition to violence, and ignore the repeated studies showing that there is no demonstrated link between immigrants and criminal behaviour.

Catholic Charities, one of the providers who led the state’s refugee program, recently announced it would no longer be participating, saying it was focusing resources on homelessness and helping at-risk children. This came after years of community pressure from conservatives — including a 2016 billboard in St. Cloud that read, “Catholic Charities Resettles Islamists: EVIL or INSANITY?”

Paul Brandmire, a Republican member of the St. Cloud City Council who is skeptical about the resettlement program, said some white residents had come to see themselves in a fight for survival.

The refugees are “not leaving,” Brandmire said.

“They’re becoming American citizens. And they have every right to, but this is killing us,” he continued. “This is the Hatfields and McCoys.”

A 2018 poll from The Star Tribune of Minneapolis reported that almost 50 per cent of Minnesota Republicans wanted the state to temporarily stop accepting refugees, and during the midterm elections the most prominent members of the state’s Republican ticket all pledged to institute a moratorium on resettlement. A New York Times poll from 2018 showed the 8th Congressional District — in the state’s northern region — was one of the few areas where 50 per cent of people said discrimination against white Americans had become as big a problem as discrimination against minority groups.

Earlier this year, at a Republican town hall in nearby Anoka County, an argument erupted between some residents and Rep. Tom Emmer because he had not backed a bill that would designate the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist group. National Republicans have also pointed to Minnesota, and the two Democratic House seats that Republicans flipped there in a tough midterm election, as proof Trump’s brand of grievance politics has political potency that may be underrated in Washington.

In the days before the 2016 presidential election, Trump visited Minnesota to pitch a proposal to halt all resettlement of Syrian refugees to America, in what would eventually become his travel ban to seven countries, many of them with Muslim majorities.

“Here in Minnesota you have seen firsthand the problems caused with faulty refugee vetting, with large numbers of Somali refugees coming into your state, without your knowledge, without your support or approval,” Trump said at a Minneapolis rally at the time. “You’ve suffered enough in Minnesota.”

Two years ago in St. Cloud, Jeff Johnson, a city councilman, introduced a resolution that would temporarily halt refugee resettlement until a study of its economic impact was completed. The idea arose, Johnson said, after he spoke by phone with officials from the Center for Immigration Studies in Washington, an anti-immigration firm that has gained influence in the Trump era. The resolution was defeated, but its introduction caused significant uproar in St. Cloud, and pushed some residents to form or join opposing community groups.

Among them was a pro-refugee organisation, #UniteCloud, that has become a prominent force in trying to build relationships and a sense of community across demographics.

Natalie Ringsmuth, a white St. Cloud resident who formed the #UniteCloud group, said Trump had “made people feel bold in not being ‘Minnesota nice’ anymore.” Ringsmuth runs a website that highlights positive stories about the city’s refugee community, and recently made a welcome video that asks local immigrants questions like, “What do you want people to know about Muslim women?”

“Things are fraught. And they’re fraught not only in St. Cloud, but in central Minnesota,” Ringsmuth said. “What might have been talked about only in kitchen tables or small groups is now prime conversation for the public.”

Bob Carrillo, a former radio host who lives in St. Michael, Minnesota, and has gained prominence for his anti-immigrant stance, said Trump had given voice to the concerns of “long-time Minnesotans.” At a coffee shop in St. Cloud, Carrillo also set a framed picture of his white grandchildren on the centre of the table, meant to amplify the emotional impact of his xenophobic thesis: that Muslims pose an existential threat to the safety of his family.

“They’re two per cent of the population right now, and in five to 10 years they’ll be at five per cent,” Carrillo said. “At that point, we’re done for.”

‘It’s hard to be accepted for who you are’

Kleis, the city’s mayor, sees it differently. He lauded the community-building activities the region has undertaken, which includes get-to-know-your-neighbour potlucks at the local library and citywide surveys asking “Is St. Cloud a friendly community?” The local newspaper, The St. Cloud Times, ran a series of fact checks to debunk myths about refugees and immigrants.

“I’d rather focus on building community than being reactionary,” he said.

Jaylani Hussein, the executive director for the Council on American-Islamic Relations in Minnesota, said St. Cloud was the “epicentre” of anti-Muslim sentiment in the state. Hussein condemned people like Kleis and other members of the Republican Party, who he said had been too neutral as xenophobia festered within their ranks.

“For me, the saddest part is that the majority of people in the St. Cloud region are good people who refused to step up,” Hussein said. “But it’s the fact that they don’t want to get involved and makes it seem like St. Cloud is all a bunch of people who accept this.”

Ekram Elmoge, a 21-year-old who resettled in St. Cloud from Somalia about five years ago, described the city as “diversity without inclusion.” Elmoge said she had been harassed by white residents, who have yelled, “Go back to your country” and “You’re here for free money.” She is currently enrolled at St. Cloud State University, where Palmer used to be a professor.

“It’s hard to be accepted for who you are,” Elmoge said. “The people here who have accepted me have been white. But the people who have not accepted me are also white. They say ‘go back to your country’ and ‘you make St. Cloud a bad place to live.’”

Dateline is an award-winning Australian, international documentary series airing for over 40 years. Each week Dateline scours the globe to bring you a world of daring stories. Read more about Dateline

Have a story or comment? Contact Us