They warn. They plead. They scold and cajole. Forecasters and public officials will try just about anything to get residents to flee coastlines ahead of a hurricane. Last year as Hurricane Harvey barreled toward the Gulf Coast, the mayor pro tem of Rockport, Texas, said people who insisted on staying should “mark their arm with a Sharpie pen — put their Social Security number on it and their name.”

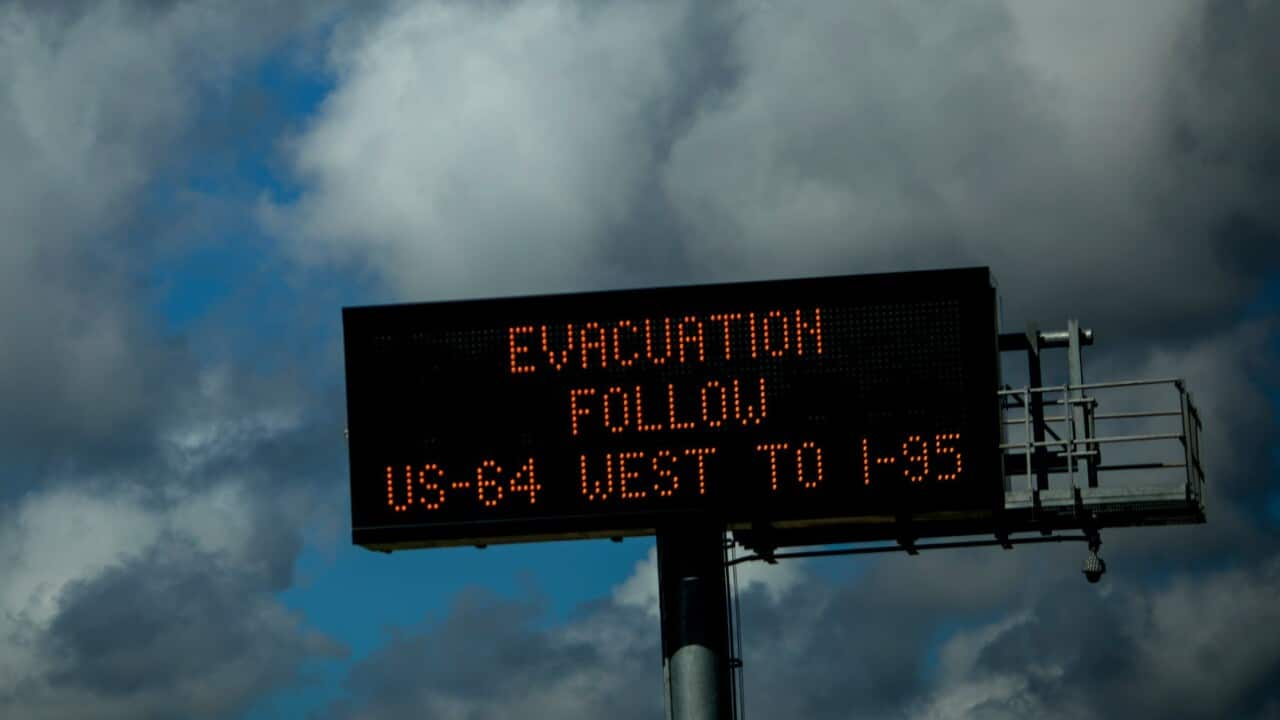

Fearing that Hurricane Florence could also be deadly, the governors of North and South Carolina ordered evacuations this week in many coastal counties. But experts know that not all residents will heed the warnings, and some say part of the reason is that storm forecasts and risks are inadequately communicated to the public.

“There’s a big gap between the forecasts that are available within the weather community and in some cases the information that people receive and are able to use,” said Rebecca Morss, a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo.

The ‘cone of uncertainty’ is confusing

A prime example of that perception gap is the familiar “cone of uncertainty” seen in hurricane tracking maps, which can be easily misread.

“The cone is misunderstood,” said Jeff Masters, a meteorologist with the forecasting service Weather Underground. “A lot of people look at the cone and think, ‘Oh, that’s the width of the storm, or that’s the area that we expect to get the impacts.’ But no, that’s where we expect the center of the storm to track.”

Even if the eye of the hurricane stays within the cone, which it does about two-thirds of the time, people outside the cone can still experience catastrophic winds, floods and storm surges.

Water is deadlier than wind

A hurricane’s category, which refers to the storm’s powerful wind speeds, also captures attention. (Hurricane Florence is currently a Category 4 storm.) But the storm surge, the rising water pushed ashore by those winds, is far deadlier than the wind itself, mostly because of drownings. The storm surge does not correlate with the hurricane category.

“The reason you evacuate is for the storm surge,” Masters said. “You don’t need to evacuate for winds — it’s better to shelter in place.”

Hurricane Florence is expected to create significant storm surge in North Carolina, in part because human-caused climate change has raised sea levels in the region by several inches since 1954, the last time a Category 4 storm hit the state.

Hurricane winds push water the way a snowplow pushes and piles up snow, said Arthur DeGaetano, director of the Northeast Regional Climate Center at Cornell University. “Those persistent strong winds blowing in the same direction literally pile up the water,” he said.

The speed of the storm surge can catch people off guard, said Julie Demuth, a research scientist who works with Morss. “If they think they have three hours to get out of the way, or a day to get out of the way, when in fact storm surge in some cases can cause inundation — deep inundation — in a matter of minutes, then that shapes how they think about what they’re able to do and how they can respond.”

The threat isn’t limited to the coasts

Even the height of the storm surge may not reflect the true danger, DeGaetano said. “The impact of the surge is not necessarily how high it is but how far inland — how far horizontally — that that amount of surge will eventually flood when it reaches the coast,” he said.

Hurricane Florence may create additional complications after making landfall. The storm is expected to stall over the region for days, dumping as much as 2 feet of rain, including over inland regions.

“If you live next to a river that’s been subject to repeat flooding over the last few decades, you might also want to consider leaving if you’re in eastern North Carolina, because we’re going to see a lot of freshwater flooding from heavy rains,” Masters said.

Here’s what scientists want to change

Morss and Demuth, the scientists who work at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, are part of a growing social research effort to understand how people respond to weather messages.

It is undeniable that improved weather forecasting has helped drive down deaths linked to extreme weather. Still, there is room for improvement: As Hurricane Sandy approached New Jersey in 2012, only 49 percent of coastal residents under mandatory evacuation orders left before the storm, according to the Monmouth University Polling Institute.

Morss and Demuth conducted a focus group and found that many participants had difficulty grasping storm surge information. So they tried using different visual and written messages to see if they better communicated what storm surge could look like at different levels: 1 foot, 3 to 6 feet and 6 to 9 feet.

“We found that for some people it really helped them visualize the risk and understand what it was going to be or what it could be,” said Morss.

One limitation of surveys and interviews is that they happen after the fact, which means participants can’t provide detailed recollections of what they were doing at specific times or in response to specific information. So the researchers are turning to Twitter for a real-time record of what people are thinking, doing and saying as a weather event approaches.

Twitter “gives us a sense of when they do start talking about weather information, how that fits into their broader lives, and what are the kinds of pieces of information that really attract the attention,” Demuth said.

The National Hurricane Center, which produces the hurricane forecast maps that include the cone of uncertainty, said it would be using social science to study improvements. The center’s storm surge graphics were already updated last year based on social studies, said Dennis Feltgen, a spokesman.

Morss and Demuth cautioned that better messaging was only part of the battle. No matter how good the information is, many people cannot act on it for health, financial or other reasons. During Hurricane Katrina, for example, many people did not evacuate because they lacked access to a car or had nowhere to go.

Demuth recalled interviewing a woman in her 70s or 80s who had used an underground shelter to survive a tornado in northern Arkansas. “She said that had her son-in-law not come home, she would not have been able to go to that shelter, because she’s too weak to be able to get the door open,” Demuth said.

“The people who live next door to her, a family of three, was killed because they were not able to get underground in time.”

Watch America's First Climate Change Refugees in the player at the top of the page

Dateline is an award-winning Australian, international documentary series airing for over 40 years. Each week Dateline scours the globe to bring you a world of daring stories. Read more about Dateline

Have a story or comment? Contact Us