The pace of growth in China’s economy accelerated last year for the first time in seven years as exports, construction and consumer spending all climbed strongly.

At least, that’s what the government says.

In reality, the pace of growth in China’s economy is anybody’s guess. Various signals suggest China’s growth did speed up last year, which could give the government the room it needs to tackle an accumulation of serious financial, environmental and social problems this year.

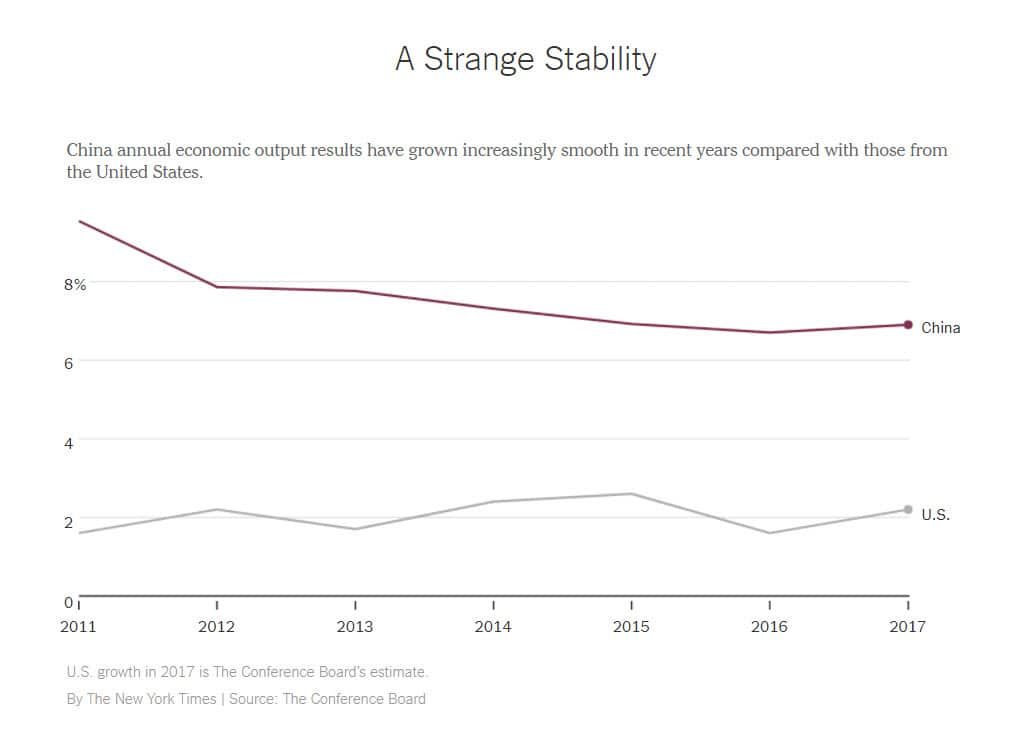

But measuring the size and health of the world’s second-largest economy can be difficult at best. Its official figures have become implausibly smooth and steady, even as other countries post results with plenty of peaks and valleys. Officials in far-flung regions are admitting their numbers are wrong. And outside experts crunching the data have come up with different — and usually weaker — results.

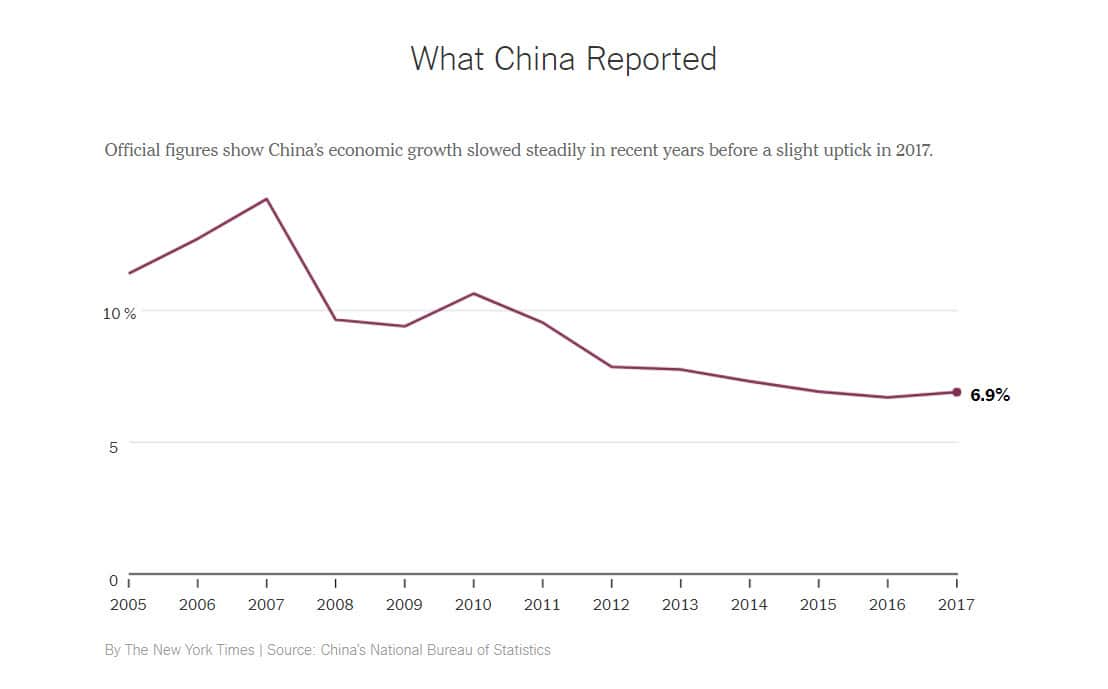

The National Bureau of Statistics announced on Thursday that the economy expanded 6.9 percent last year, up slightly from 6.7 percent in 2016 and breaking a trend of gradual slowing that began in 2011. For the fourth quarter, the bureau reported economic growth of 6.8 percent over a year earlier.

Strength in exports, retail sales and the property market has helped spur growth, putting China in a better position to tackle problems including a sharp climb in debt, severe pollution and other problems.

But that growth has come at a high price: rising borrowing that has triggered downgrades of China’s sovereign debt rating by credit rating agencies; severe pollution of China’s air, water and soil; and persistent social problems associated with the movement of tens of millions of workers to cities who had little choice but to leave their children in their hometowns. President Xi Jinping signalled at an important Communist Party meeting in October that he wanted to address some of these chronic problems and that the country should no longer emphasise maximising economic growth at almost any cost.

China’s annual growth figures have long been quite steady. Other large countries have had somewhat steadier growth than usual in the last several years. But China’s quarterly growth figures are suspiciously smooth, unlike quarterly growth in many other countries.

Politics are a major reason. Local officials often face pressure to meet targets from the central government. At the first hint of economic weakness, they have tended to step up spending to stabilise economic output.

Increasingly, China is owning up to data shortcomings, particularly in provincial data. The region of Inner Mongolia revealed this month that two-fifths of the industrial production it reported for 2016 did not exist. A year ago, Liaoning Province in northeastern China revealed that local governments had padded their economic growth statistics from 2011 to 2014.

Tianjin, a sprawling metropolis, briefly posted on one of its official websites last week that previous data had been inflated. The post was quickly deleted.

Ning Jizhe, the director of the National Bureau of Statistics, said at a news conference on Thursday afternoon in Beijing that there had long been discrepancies between provincial and national data, but that the gap had been narrowing. “Local data will not influence the reliability of national statistics data,” he said.

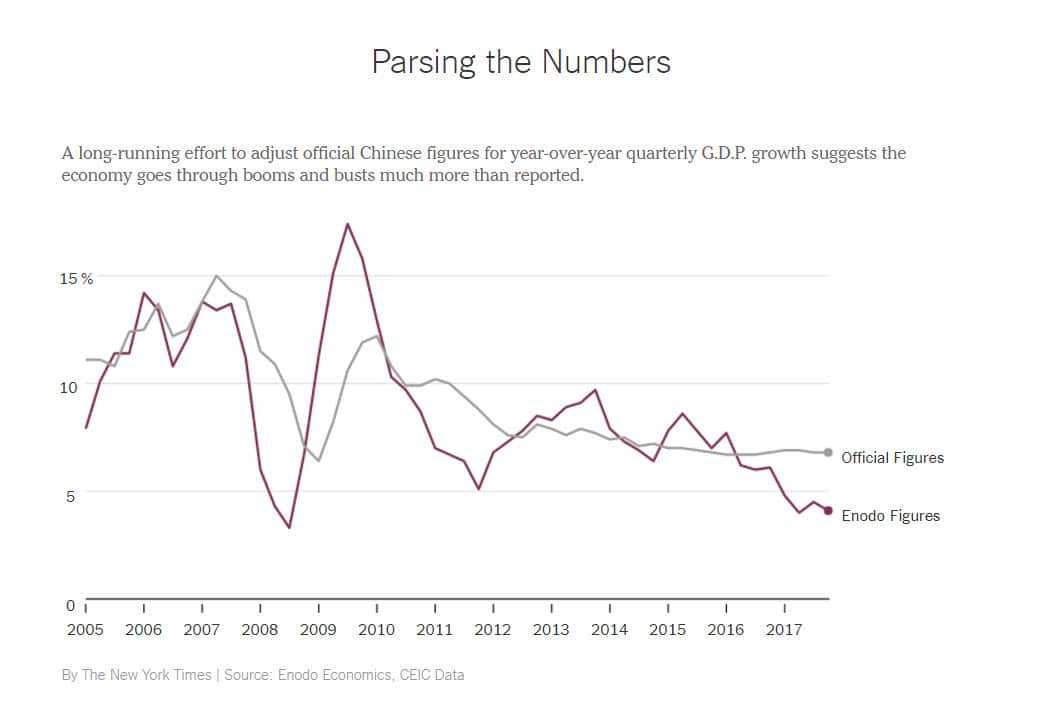

It can work the other way, too: Some economists cite evidence that China also understates its growth during booms to smooth its results.

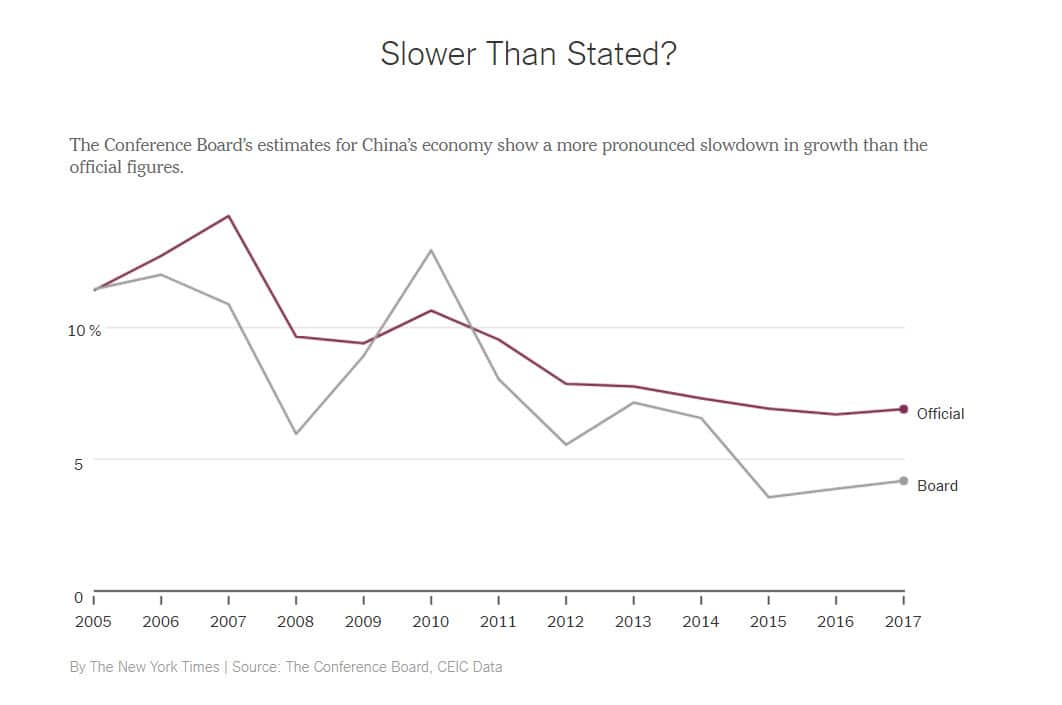

Economists who try to estimate actual growth tend to come up with lower numbers.

The Conference Board, a business group based in New York, takes Chinese data for agriculture, construction and easily counted services, like transportation, as accurate. It then adjusts the official data for irregularities in industrial production and in less easily counted services, like health care.

The result shows Chinese growth to be somewhat lower than reported, particularly in years with weak growth. At the same time, by understating the depth of the slowdown in 2015 and 2016, the official figures also appear to understate last year’s improvement.

The Conference Board’s results suggest the current uptick is real. But the board worries that much of the growth has come from recent lending, despite China’s already huge accumulation of debt in previous years.

“We think the recovery is real,” said Yuan Gao, the senior economist in the Beijing office of the Conference Board. “We’re just concerned that a lot of it is built on bad debt.”

Diana Choyleva, an economist at Enodo Economics in London, also produces growth figures that are below the official results.

Many economists, including Ms. Choyleva, believe Chinese officials understate how much prices rise in China. That tends to overstate growth.

She adjusts official figures based on price data and seasonality. She then finds that the Chinese economy tends to track Beijing’s stimulus efforts, which produce booms, and its moves to curb unsustainable lending, which produce slowdowns.

China’s statistical issues go beyond mere government meddling. The country’s economy is vast and quickly changing. Officials still struggle to catch up with years of growth and to modernise data-gathering practices.

“It’s just simplistic to say they lie or they don’t lie,” said Pauline Loong, the founder and managing director of Asia-analytica, a Hong Kong consulting firm specializing in mainland China. “They define their data differently, and they keep changing their definitions.”

Click Here to watch the full episode: China's Family Sacrifice

Dateline is an award-winning Australian, international documentary series airing for over 40 years. Each week Dateline scours the globe to bring you a world of daring stories. Read more about Dateline

Have a story or comment? Contact Us