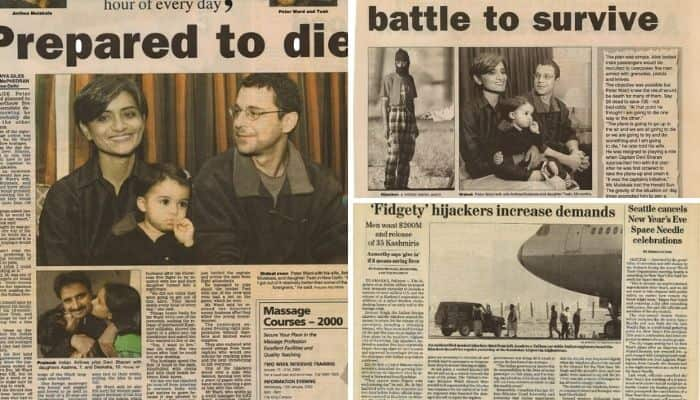

It was Christmas Eve 1999 when Peter Ward boarded Indian Airlines Flight 814 bound for Delhi, to meet family and friends for the holiday break.

The typical 90-minute trip, interrupted shortly after take-off by a band of hijackers, resulted in an eight-day siege that would alter the lives of 171 passengers forever.

“From the moment I entered that plane to the time I stepped out, it really changed me,” Peter said.

Taking a seat in business class, a then 36-year-old Peter, noticed two passengers board that gave him an “uneasy feeling". They were wearing tracksuits and beanies which Peter remembered being out of place for that section of the plane.

As tray tables were pulled down and in-flight meals were served, the men Peter noticed earlier emerged from the two forward bathrooms in balaclavas and brandishing guns – yelling, “Move, move".

He swiftly headed towards the back of the plane, only to see three more hijackers emerge.

“They were corralling passengers and pushing us into the mid-section of the plane, demanding that everyone bunch up,” Peter said.

“An Indian passenger objected. One of the hijackers suggested that he go and make his objection clear to what would emerge as the head hijacker.

“In doing so, they executed him in front of all the other passengers.

“They decided that they needed to make a point, and they were extremely ruthless in how they did it, and that allowed them to exert total control.”

Peter recalls absolute silence falling across the plane as he wrapped his blindfold tightly around his eyes and crouched over. Some days he can still feel the pain in his neck from keeping his head down for the next eight hours.

Now in control of the aircraft, the hijackers flew to northern India, then to Pakistan, Dubai and finally they touched down in Kandahar, Afghanistan, where the plane remained for the next week.

In the seven days he spent trapped on the tarmac, Peter witnessed events that still astonish him.

A Japanese woman who refused to let the hijackers interrupt her trip, occasionally raiding the drinks locker to pair with the cigarettes she smoked in defiance of their presence.

Passengers trying to endear themselves with the hijackers, chatting and joking and performing “like an entertainment hour” at night.

“You could see it happening, a manifestation of Stockholm Syndrome, and you’re sitting there thinking, what the hell is happening here?” Peter said.

“These people are going to kill you. They have killed. They will kill.”

While tensions simmered on the tarmac, the motivation for the hijacking became clear.

Negotiations with the Indian government for the release of three Pakistani militants, in exchange for the passengers, began with ominous nightly deadlines.

“They would say ‘right, blindfolds on’ and they would walk around the plane and you could hear the footsteps of the hijackers as they’d walk around,” Peter said.

“All of a sudden they’d stop, put a big hand on your shoulder, grab you and take you.”

On the sixth day, that hand fell on Peter’s shoulder.

“They dragged me to the front of the plane where the doors were open,” Peter said.

“I turned and faced him and said ‘Right, you’re going to have to put the gun right between my eyes, rather than at the side of my head’"

“It was cold steel and I thought, well, it really is a gun.”

But, as they’d done each night previously, Peter was allowed to return to his seat as the other passengers had been.

Not long after, the passengers noticed the hijackers vanish from the plane.

“They just left and my understanding was that they just boarded a little bus and rode off into the sunset,” Peter said.

“The Taliban Foreign Minister came on to the plane and said, ‘You’ve been liberated by the Taliban, men first, women cover your heads, the plane is wired to explode’."

Crossing Kandahar’s dusty airstrip and boarding another plane, on the eve of the millennium, Peter flew back to Delhi and stepped out of the terminal - melting into the crowd and back into his life.

The Indian government agreed to let Maulana Masood Azhar, Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh and Mushtaq Ahmed Zargar free in exchange for the passengers.

Those men are alleged to have participated in further acts of terrorism throughout the 2000s.

“My whole confidence in humanity was just shot."

“I entered as a very confident, I'd say fairly gregarious, outgoing person and as I came out my trust was taken away.

“It affected my marriage, I'm no longer with my wife - because I became insular.

“It goes right back to the very point of that hijack, because those two gentlemen who got on that plane, they just looked like passengers.

“Then they turn out to be gun-wielding, grenade-carrying executioners, and for the rest of your life, you’re looking at everyone and thinking ‘Who could they really be?’”

Peter admits he returned to work too soon, didn’t get the right support, or seek counselling in a meaningful way. But he says he’s back to where he needs to be.

“I’m much better now than I was, and I have a lot of structural things to thank for that,” Peter said.

“I have a long-term partner who’s been really helpful, I work for a really good company and I have a good boss who’s been really supportive.”

Insight is Australia's leading forum for debate and powerful first-person stories offering a unique perspective on the way we live. Read more about Insight

Have a story or comment? Contact Us