Cost of living spikes are pushing our living standards down. Watch Insight episode Tough Time$ on SBS On Demand.

Stream free On Demand

Tough Times

episode • Insight • News And Current Affairs • 52m

episode • Insight • News And Current Affairs • 52m

When Steve Charman's marriage ended around 20 years ago, he decided to move from Melbourne to the country. But just as he was signing the sales papers on his new property near Castlemaine in regional Victoria, the agent dropped a bombshell: "You do realise you're off the grid here, right?"

Steve pressed on and bought his home in Chewton Bushlands, an off-grid community of around 100 people and one of Australia's first.

"I'd been interested in conservation all my life and it felt time to be true to my beliefs, to have a lower energy profile," he told Insight.

The 118-hectare community started in the 1970s after an entrepreneur bought the land and subdivided it into lots. Over time, people moved in and built alternative homes made of mudbrick and reclaimed weatherboards.

Steve says those early days would have been "really hard" for residents, with houses having "very crude systems or no power at all".

His own house had solar panels connected to old batteries, which gave him patchy power.

"I'd be in winter and the lights would just go off when the batteries went flat. It was certainly different from what I'd been used to."

Steve is in the process of updating his battery system, which isn't enough to run an electric fridge or even toasters or kettles (he relies on bottled gas). But his new battery system and extra solar panels should allow him to have reverse-cycle air conditioning and even an electric blanket in winter.

"I'll be able to have a lot of things that I could have only dreamt about 20 years ago," he says. "If you can afford a good system, you'd never know you weren't on the grid."

Unplugging our homes

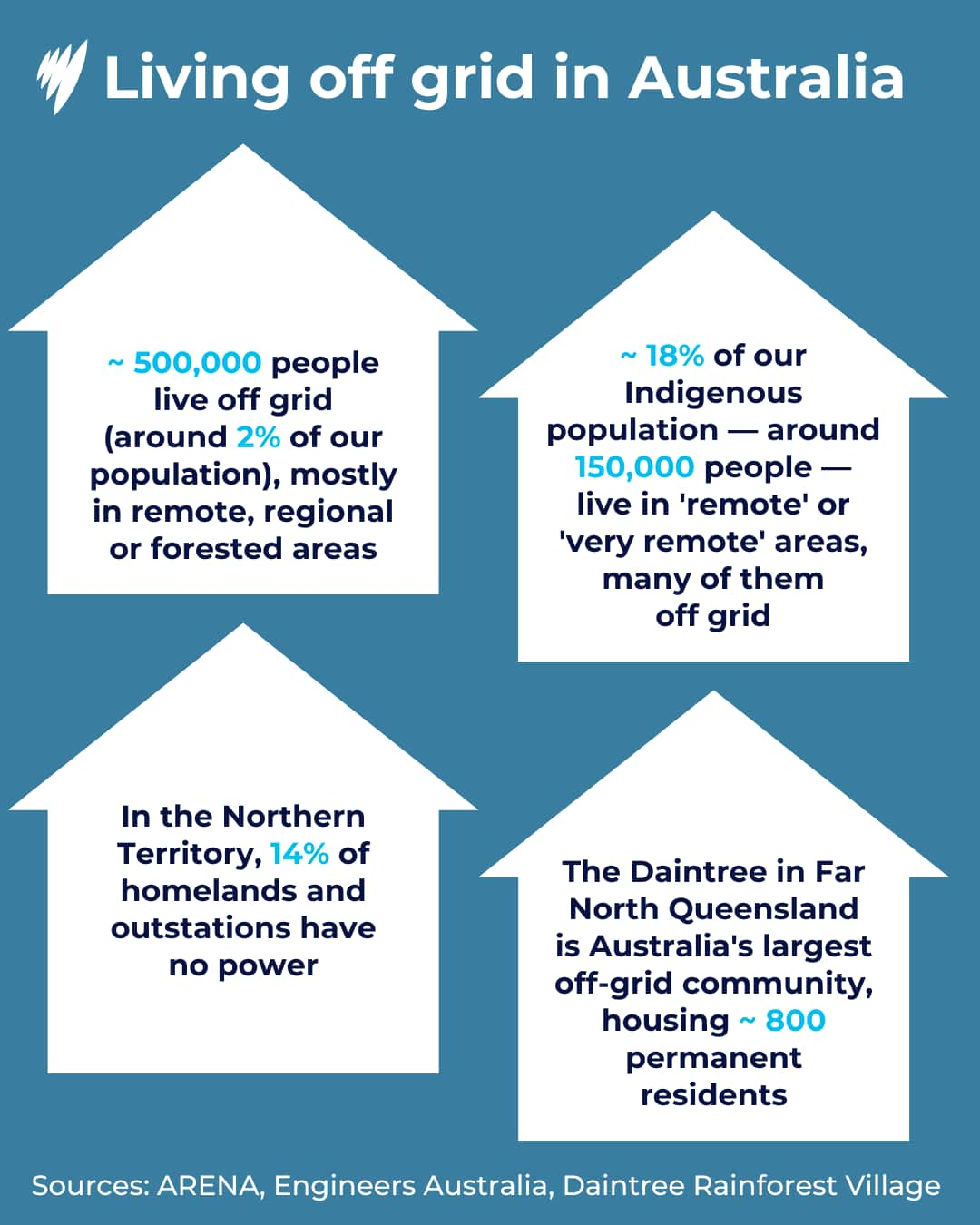

In a vast country where more than 85 per cent of our landmass is classified as "remote" or "very remote" — to which extending the power network is often prohibitively costly — off-grid communities have learned to thrive.

Some use diesel generators or solar microgrids, while others have no power at all.

Power in off-grid regions can be unreliable, costly, and prone to outages due to equipment failure or pre-paid meter disconnections.

Some people, especially residents of Indigenous communities, live remotely for cultural reasons and would prefer to have mains power.

But for more and more Australians, living off-grid has become a choice.

Annie Smallmon has lived in the Starlight Community in Queensland's Sunshine Coast hinterland since 2011 after finding the peace and quiet helped to reduce her Parkinson's disease symptoms.

Established in the 1970s, the 130-hectare site houses around 35 people relying on rainwater, septic systems, solar panels and battery storage, plus back-up generators.

Annie remembers the "big deal" when the community acquired batteries and could finally have lights on at night, though she says her lack of sunlight in the valley still isn't enough to power a TV.

But she's learned to love living this way.

"The houses here have a rustic and eclectic vibe. And living off grid is easy — and cheaper," she told Insight.

"There is no way I could live on my pension in a town and pay electricity and water bills. I just wouldn't survive. Here, I've got five acres to walk around in and enjoy. It's very restorative."

Crunching the numbers

Dr Peyman Akhgar, a lecturer in architecture and design at Queensland's Griffith University, has researched off-grid living. He says falling costs of solar PV systems and batteries now make off-grid living a more viable option than it once was.

"Today, off-grid communities have access to most technologies such as computers and the internet, so they would not feel much different from those connected to the grid."

He says the desire to consume less and live in a more sustainable and resilient way is leading more Australians to unplug their homes.

Further incentives include raising children away from modern challenges, independence, cheaper and potentially more reliable electricity, and living close to nature.

"It's also an attractive option for those who believe in the value of community, as living off grid requires a much closer connection with and support from other community members," Akhgar says.

However, he says the high set-up costs of off-grid systems, particularly batteries, can be a challenge for some, while they can also carry expensive repair and maintenance fees.

Steve at Chewton Bushlands agrees costs can be deceiving.

"When I tell people I haven't paid a single power bill in 20 years, they go, that's fantastic! But the person who set this up in today's money would've paid around $50,000," he says.

"To upgrade my system may cost me $20,000. I think there's a lot of people who'd love to do this, but they don't have the money."

While homes in off-grid communities can also be significantly cheaper than those connected to the mains, they may still cost more than many would expect.

At Chewton Bushlands, where residents buy the property and the lot, people pay up to $700,000 for "beautiful homes on big amounts of land", Steve says.

At Starlight, people don't own the land, so are unable to secure a loan, forcing them to buy with cash. With a recent four-bedroom home selling for just under $700,000, this isn't doable for everyone, though Annie says the previous house sold for $400,000.

And while Steve may save a few hundred dollars each year by not paying sewage and waste disposal fees (he uses a septic system and his local tip and recycling centre), he still has to pay around $1,200 a year in council rates for using the land and local infrastructure.

Showing what's possible

Jonathan Keren-Black and his wife Sue moved to Narara Ecovillage on the NSW Central Coast from Melbourne four years ago, seeking intentional community living with a lighter footprint in a warmer climate.

Unlike Chewton Bushlands and Starlight, Narara's around-200 residents have access to mains power as well as water, sewage and waste disposal systems. However, they choose to generate their own power through an advanced solar microgrid and communal batteries.

"On most days we generally export about a megawatt of spare power," explains Jonathan. "But most of the time we're off-grid. Everybody has to have solar in the village."

For them, living off grid is not so much a need, but a demonstration of what's possible.

Not only do Narara residents generate their own power but they also grow their own vegetables, buy essentials in bulk and distribute to residents, have energy-efficient homes, and house guests in an accommodation block to avoid the need for spare rooms.

Jonathan says once people realise their community is not full of "hippies, drug users and wife swappers", many wonder why they haven't considered living in an eco village before.

Narara has a list of people "on the journey to joining" who become more involved in the community in order to discover if it's right for them.

"I think eco villages are certainly becoming more popular and once people live here, they seem to want to stay," Jonathan told Insight. "We love the peace and quiet and having the forest on our doorstep. I wake up every morning feeling lucky and blessed to live here."

But when decisions are made collectively — from how to manage electricity to whether to welcome more people — conflicts inevitably emerge.

At Narara, certain people have expertise in listening to people's challenges, and they mediate or call in a professional when necessary, Jonathan says.

Australians leaving the grid

In the future, Akhgar predicts we'll see more off-grid communities — even among those who have access to mains power.

"It's a misconception that off-grid living is only suitable for people living remotely. Our research shows that people intentionally choose to live off-grid, even when they have the option to connect," he says.

"Not only are off-grid technologies becoming cheaper and more accessible, but the impact of climate change will affect grid reliability, increasing the likelihood of grid defection."

For those wishing to set up an off-grid community, he says challenges can include "an ambiguous regulatory environment and limited knowledge among some community members about how to live off the grid effectively".

Jonathan agrees that setting up an eco village or intentional community can be a "long and complicated process".

"If the government found a way to make it easier to establish them, I'm sure they would take off rapidly," he says.

"They could be a great solution to the housing crisis."

Steve at Chewton Bushlands believes that over time, off-grid communities have become more mainstream.

"A lot of the people I first met here were definitely hippie-ish — they were different from your normal person, they had strong principles and they put up with a lot more."

"Today, as systems have become cheaper and more sophisticated, there are fewer inconveniences."

He says as Chewton's original residents become elderly, a new generation is moving in.

"We have younger couples moving in, so we're expecting more children here. People come to Chewton to be by themselves and to be in nature, but still have a social connection.

"I'm not looking forward to the day when I'm older and forced to go back into a suburb again."

Watch your favourite Insight episodes around the clock on SBS On Demand's dedicated Insight channel. For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.

Insight is Australia's leading forum for debate and powerful first-person stories offering a unique perspective on the way we live. Read more about Insight

Have a story or comment? Contact Us